Robert Louis Stevenson, celebrated author of Treasure Island (1882-3), Kidnapped (1886), and "The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde" (1886) was a lifelong connoisseur of "penny dreadfuls": illustrated serial fiction that targeted working-class readers. In Stevenson's childhood, his nurse Alison Cunningham often read dreadfuls to him. In adulthood, Stevenson was haunted by one serial in particular. This was A Mystery in Scarlet by “Malcolm J. Errym,” the pseudonym of James Malcolm Rymer (1814-84).

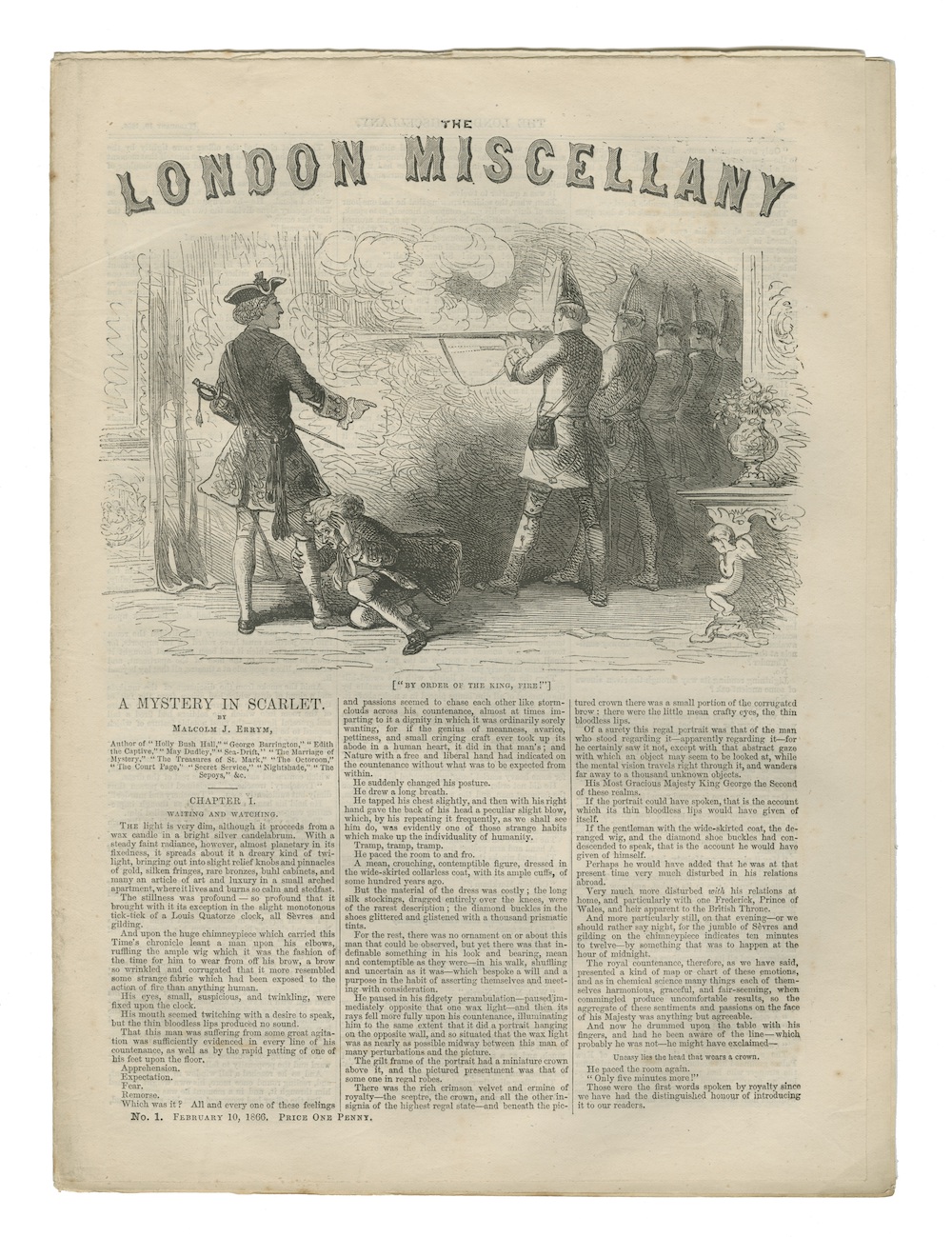

In 1866, when Stevenson was sixteen years old, A Mystery in Scarlet appeared in the penny periodical The London Miscellany. The leading (front-page) story for most of its eighteen installments, A Mystery in Scarlet made a great impression upon him. “Memory may play me false,” he recalled twenty years later in an essay in Scribner's Magazine, “but I believe there was a kind of merit about ERRYM,” as A Mystery in Scarlet “runs in my mind to this day” (Stevenson, "Popular Authors" 126).

The persistence of A Mystery in Scarlet in Stevenson's memory troubled him. As he informs Scribners’s readers, he clearly recalled the tale's villains, the tyrannical King George II and his sycophantic valet Norris. However, he had forgotten the resolution. Consequently, Stevenson promises, “if any hunter of autographs […] can lay his hand on a copy even imperfect, and will send it to me care of Mr. Scribner, my gratitude will drop even into poetry” (Stevenson, "Popular Authors" 126).

Perhaps someone responded to this plea. By April 1889, Stevenson possessed a copy of A Mystery in Scarlet. Rereading it confirmed his debt to Errym. “I liked it hugely,” he wrote to his former neighbor Adelaide Boodle, “far better than I ever expected; and see that Mr. Errym [...] had a genuine influence on me, and wish I had his talent, above all in sketching girls” (Mehew 396), one of Stevenson's own most obvious literary deficiencies.

Despite Stevenson's exuberant praise, A Mystery in Scarlet has never been reprinted, nor has it received any scholarly attention. This neglect might be due to scholars' assumption that it is irretrievably lost. The Orlando Project biography of Rymer claims that “the text does not survive." However, it certainly does. At least two complete copies and one partial copy exist in public collections. Furthermore, A Mystery in Scarlet deserves recovery, not only because Stevenson rated it so highly and was influenced by its author's corpus generally, but for several other reasons.

One reason is the engagement of A Mystery in Scarlet with intense topical debates about the extent to which working-class men might be able to contribute to the British polity as active, ethical citizens. A Mystery in Scarlet is also intriguing as a relatively late, relatively short contribution to the genre of the court mystery, which was popularized in England by Rymer's inspiration and sometime editor George William Macarthur Reynolds (1814-79). For these reasons and others, I have compiled this critical edition of A Mystery in Scarlet. I intend it to prove particularly useful to researchers and students of the penny press, Victorian working-class literature and political life, Stevenson, and the illustrator of A Mystery in Scarlet, "Phiz" (Hablot K.Browne, 1815-1882).

James Malcolm Rymer, alias "Errym"

Stevenson never knew the true identity of the author of A Mystery in Scarlet. Familiar with penny fiction attributed to “Captain Merry, USN,” he correctly deduced that “Errym” is an anagram of “Merry." However, he speculated that “Merry” was the author’s real name. He never knew that “Merry” and “Errym” are both anagrammatic pseudonyms employed by James Malcolm Rymer. The most successful member of a London literary-artistic family of Scottish origin that spanned the Romantic and Victorian eras, Rymer was one of the most influential and prolific authors of "penny bloods" and "dreadfuls." These cheap illustrated serials often featured dramatic, lurid plots, historical settings, and themes of rebellious or revolutionary criminality.

As some critics clarify, "penny bloods," flourishing circa 1837-60, and targeting family audiences, are distinctly different from later, less lurid "dreadfuls" (circa 1860-90), which were marketed specifically to juvenile readers, especially boys (Léger-St. Jean, Price One Penny). Victorian commentators often used the terms "penny blood," "dreadful," and, less commonly, "awful" interchangeably and without much critical awareness. In The Reminiscences of a Country Journalist (1886), Thomas Frost, author of penny fiction and journalism, claimed that his contemporaries employ the term "penny dreadful" to describe any literature that costs one penny per copy, contains fiction of some kind, and is implicated in the moral corruption of working-class readers, especially children. "I don't know what constitutes a 'penny dreadful,'" Frost claims to have told a "City gentleman" (financier) outraged by that literature's existence. "It is the kind of literary ware we often hear of when an errand-boy has robbed his employer," and has no monopoly on gratuitous violence, since "there are horrid stories in Shakespeare" (Frost, Reminiscences 177). In other words, a literary publication becomes a penny dreadful when an elite critic advances a moral objection to it.

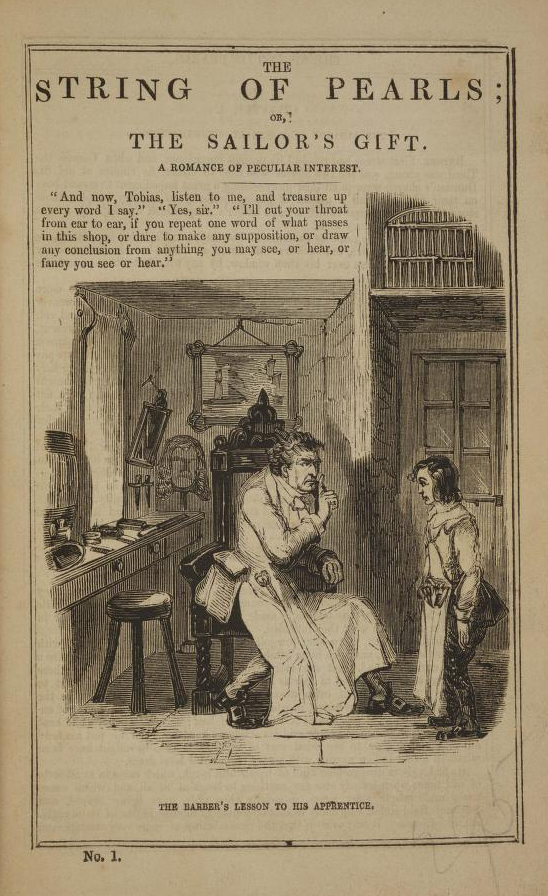

Throughout the 1840s-60s, Rymer composed penny fiction and also edited some of the penny periodicals that carried it. His earliest regular employer in this work was the publisher Edward Lloyd (1815-1890). A sometime adherent of Chartism, after 1848 Lloyd turned away from that working-class political self-determination movement to focus on news publishing. Via this shift, argues Rohan McWilliam, Lloyd was able to construct a previously unimaginable working-class "liberal consensus" (McWilliam 209). One of Rymer’s earliest Lloyd titles, Ada, the Betrayed (1843), serialized in Lloyd’s Penny Weekly Miscellany, proved so commercially successful that for years afterward, Lloyd advertised Rymer's serials as the work of “the Author of Ada” (James, Fiction xx). The same penny blood appealed to Dante Gabriel Rossetti (Tillotson 31). Other well-received, relatively enduring penny bloods that Rymer wrote for Lloyd include Varney the Vampyre, or, the Feast of Blood (1845-7), an important precursor to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and The String of Pearls (1846-7).1 Rymer later expanded this last title as The String of Pearls, or the Barber of Fleet Street, A Domestic Romance (1850). The earliest publication to feature the character of homicidal London barber Sweeney Todd, The String of Pearls is Rymer's most enduring literary creation.

In the 1850s and 1860s, Rymer composed slightly less lurid serials for Reynolds. A prominent Chartist as well as a writer and editor of penny literature, Reynolds is now best known as the author of the long-running, controversial, and politically radical serial The Mysteries of London (1844-5). With this serial, Reynolds popularized the genre of the urban mystery, which purported to reveal the criminal secrets of the modern industrial city. The Mysteries of London and other Reynolds bloods inaugurated the "Chartist Gothic," or application of the Gothic literary mode as appropriated from writers such as the feuilleton novelist Eugène Sue to working-class reform agendas (McWilliam 202-3). Reynolds's subsequent sprawling hit The Mysteries of the Court of London (1848-56) is a prime example of the "court mystery." It focuses on Hanoverian court intrigues, corruption, and secrecy. Notably, so does Rymer's A Mystery in Scarlet, over twenty years later, making it a contribution to the genre of the court mystery.

James Malcolm Rymer. The String of Pearls, or, the Sailor's Gift. London: Edward Lloyd, 1850. Wikimedia Commons.

When Rymer wrote fiction for Reynolds or other employers, he generally worked under cover of anonymity and pseudonymity. At least once, he even used his pseudonym "Errym" socially. Under this name, he attended a company banquet for Reynolds's staff authors (Collins xx). Rymer's reticence to claim authorship of his works may have derived from the reputation of the "dreadfuls." As we have seen, middle-class critics frequently complained that Lloyd, Reynolds, and their staff writers promoted working-class idleness and violence. This belief was particularly pervasive after the 1840 execution of valet Benjamin François Courvoisier for the murder of his employer, Lord Russell. Unfortunately for the penny fiction industry, Courvoisier was widely reported to have possessed a copy of William Harrison Ainsworth’s highwayman romance Jack Sheppard, which had been serialized in Bentley’s Miscellany in 1839-40.

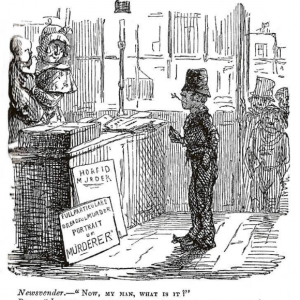

Two Punch cartoons of the 1840s endorse the myth that penny fiction acclimates working-class readers to criminality. In John Leech's "'Parties' for the Gallows" (1845), a Cockney teenager tells a newsagent "I vonts [want] an illustrated newspaper with a norrid ['an horrid'] murder and a likeness [portrait] in it” (Punch 8:187; discussed in Haywood 240). An accompanying editorial blames penny fiction for stoking sensational interest in murder. "The traders in blood and horror--the butchers of the press, for truly they are so--had to stimulate and feed the curiosity of society with periodical illustrations of murder" ("'Parties' for the Gallows" 147). In another Punch cartoon, "Useful Sunday Literature for the Masses, or, Murder Made Familiar" (1849), the working-class "Father of a Family" reads to his wife and children "[t]he wretched Murderer is supposed to have cut the throats of his three eldest Children, and then to have killed the Baby by beating it repeatedly with a Poker," while a "likeness" of Courvoisier hangs on the wall and a Bible languishes on the floor, its page block open in the dirt (reproduced in Jackson).

Notably, Rymer's younger brother Thomas was an actual criminal: a serial forger of banknotes. In 1839, Thomas Rymer was transported to Van Diemen's Land for life. In Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) and on the Australian mainland, he committed several more audacious monetary forgeries. He was convicted of forgery for apparently the final time in 1865, the year prior to the publication of A Mystery in Scarlet (Nesvet, "The Bank Nun's Tale" 39-40). Had this detail of James Malcolm Rymer's family history become widely known during his working life, it might have confirmed the critics' association of penny fiction with criminality. Rymer's careful protection of his personal identity was probably a wise measure.

While the Victorian assumption that reading "dreadfuls" creates criminality is absolutely unfounded, the penny press was not innocuous. Demonstrably, it helped to accustom working-class families to recreational reading. In a memoir of 1880, Frost recalled the penny serial as an important resource that filled a gap in working-class intellectual life. “No longer ago than the commencement of the second quarter of the present [nineteenth] century readers were very few proportionately to the population,” Frost claims, so “no editor of a periodical dreamed of addressing either them or the working class” (Frost, Forty Years 67). Frost recalls that in his childhood, his family read only the Bible, “school books,” Cobbett’s Register, and political pamphlets (67). Penny fiction gave families like his a wider and more enjoyable range of reading material.

Rymer's penny fiction in particular articulates radical political critique pitched to a target audience that, like Rymer himself, was metropolitan and working-class. As Louis James explains, Ada, features "a dominant image of class oppression," namely, "the fatal seduction of a working-class woman by an elite man," but with a twist that gives its eponymous heroine inspiring agency (James, "I am Ada!" 67). That "working-class heroine," James observes, gradually grows "self-confident... and eager to help fellow victims of 'harshness and misfortune'" (67). Maisha Wester shows that The String of Pearls “highlights anxieties about the emergence of industrial capitalism” as experienced by working-class people. Ted Geier judges The String of Pearls an “essential expression of" industrial modernity's dehumanization of various “London publics” (Geier 120). Rymer represents this dehumanization allegorically via Todd's meat-packing of human flesh (152). For Troy Boone, Rymer’s Varney, the Vampire “enables working-class readers to enter debates about violence and class typically identified with Chartist radicalism” (Boone 52). In Varney, Boone contends, Rymer tells his readers they are “[f]ree to envision other narratives for themselves” than the tradition post-1789 narrative of class revolution as mob violence” (59). Rob Breton argues that The String of Pearls and the penny blood industry in general lifted material from Chartist and radical discourse largely because it appealed to a radicalized public and because they wanted to end up on what Breton calls "the right size of history (Breton 4).

Radical rhetoric is conspicuous in Rymer's Mazeppa, or, the Wild Horse of the Ukraine (1850). In this Lloyd blood, the hero is not Byron's Prince Mazeppa, but his sidekick, a London shopkeeper named Mr. Lumpus. When Mazeppa and his Eastern European comrades demand Lumpus for their Prime Minister, Lumpus explains the disenfranchisement of his class. "Oh, pho!" he exclaims, "me a prime-minister anywhere out of England [...] would never do, and in England, I have not the capital" (Rymer, Mazeppa 492). His interlocutors are confused:

"The what?"

"The capital."

"Do you mean money?"

"No, not altogether money, although that is essential; but in England, you must know, no man can be anything or hope to be anything in the population without capital. That is to say, he must have have birth and its consequent influence, and its consequent opportunities."

"Birth?" said Mazeppa; "I thought that in England was of small amount, and that ability was the grand thing."

"Then, my dear friend, you know nothing at all about it. In England men are almost all born to be what the[y] will be. One man is born a member of Parliament; another a parson; another a lawyer, and so on; and it is about as impossible for any one not born in the classes from which members of parliament, parsons, and lawyers are made, to become either, as it would be for me to walk away with the castle of Ureka in my waistcoat pocket."

"You indeed surprise me. I thought that England was the most liberal country upon the face of the earth."

"Tush! It's all humbug." (492-3)

This sort of dialogue was calculated to sympathize with an aggrieved British working class and to articulate their grievances.

It is therefore not surprising that the penny blood's progress was curtailed by the law. In 1857, the Obscene Publications Act, also known as Lord Campbell’s Act, authorized the search of any premises suspected of harboring “obscene” literature. The Act also authorized police to seize and destroy such literature. This legislation had a chilling effect on publishers of penny bloods. Lloyd abandoned the literature industry, turning instead to focus on news. Rymer survived the ban to write less gory but equally politically engaged penny dreadfuls for new publishers, such as Reynolds's printer John Dicks. In his new professional circle, Rymer quickly became a “major” house author, just as he was when working for Lloyd (James, ODNB 494). Rymer's dreadfuls of this period include the highwayman serial Edith the Captive, or, the Lost Heir of Warringdale Manor (1861), which Stevenson read and appreciated, and its sequel Edith Heron, or, the Earl and the Countess (circa 1870).

The London Miscellany

In 1866, Rymer began editing a new penny periodical, The London Miscellany and published A Mystery in Scarlet as its leading serial. He designed The London Miscellany to appeal to readers of his dreadfuls, his earlier bloods, and of the new genre of the sensation novel, but in editing the periodical, he took pains to avoid suspicion of immorality. He reveals these goals in a fictional dialogue, “The Editor and Paterfamilias,” published in the London Miscellany’s February 10, 1866 first number.2 “You will cater largely in the ‘fiction’ way,” Paterfamilias establishes. “Now, what will be the nature of your Romances? Will they be all milk or of a more ensanguined colour?”

Ed. Something between—say couleur de rose [sic].

Pater. Yes: but will they be sensational?

Ed. You mention that word in a tone of alarm. Now, I am happy to say that those romances which rake up the gutter of human depravity are a commercial mistake. Their hideous portraits repel most readers […] but, if you ask me whether our tales will bristle with incident, curl round the reader, and drag him along with them, I answer that we will use any known recipe for effecting that object. You must not be deluded by a cuckoo cry. The most “correct” magazines endeavor to be sensational. (The London Miscellany 12)

With this retort, Rymer’s editorial persona reassures Paterfamilias and brazenly questions the morality of upscale periodicals. In the pages of The London Miscellany, the Editor (Rymer) keeps up this rhetorical pose, at one point warning the reader that Lord Byron—a writer frequently quoted and cited in Rymer’s earlier bloods, and the source of his own Mazeppa, “was a tippler [drunk]” whose ‘vile Don Juan’ is “unfit for any woman to read” (The London Miscellany 130).

In practice, The London Miscellany’s "rose" proved a decidedly deep red. The first volume of the magazine offers two short tales by “Lewis Monk” (30, 62). This pseudonym invokes Matthew G. Lewis, author of The Monk (1796), which penny bloods frequently emulated (Hoeveler 246). The William Heard Hillyard serial The Fair Savage, A Story of an Indian War-Trail, which runs in the first eleven numbers of The London Miscellany, features as its villain a Gothic attempted rapist. The London Miscellany no. 15 incorporates the tale "The Barber Fiend" (The London Miscellany 239). This tale is a recycling of the anonymous 1824 story “The Murders in the Rue de la Harpe," the major source of the plot of Rymer's 1846-7 masterpiece The String of Pearls . Another allusion to the penny bloods of the 1840s permeates A Mystery in Scarlet. That serial's protagonist, Captain Weed Markham, shares a name with Richard Markham, the picaresque hero of Reynolds’s The Mysteries of London. A minor character, Montague, shares his name with a major villain of The Mysteries of London (1844-5). These allusions to Reynolds's popular and radical work demonstrate that in The London Miscellany, the penny dreadful was not dead. It was merely buried in print of which Paterfamilias would approve.

Neither was Rymer’s political fire extinguished. In fact, The London Miscellany continues the radicalism of his earlier works. Its thematically interlinked contents consistently point out upper-class excess and irresponsibility and the need for justice for working men and the poor. In the first number, a Rymer-authored serial, Emmeline, or, the Serpent in the Wreath, introduces an early “owner” of a “lordly mansion”:

Clinging to the gilt balustrades of the staircase, his hair wildly disordered, a brocade dressing-gown, torn and disarranged, as it hung about him, and the wild fire of partial intoxication in his eyes [...] the Sybarite [...] at his nod, could have the remotest corners of the globe ransacked to his appetites and his luxuries. (The London Miscellany 6)

Reminiscent of a Continental aristocratic villain out of the novels of Ann Radcliffe---or Donatien-Alphonse-François de Sade---this character is British. His “mansion” is located in London's Grosvenor Square. Continuing this theme, an anecdote about Richard Brinsley Sheridan sees the playwright rebuke “a young wealthy heir" for “prid[ing] himself on the accident of his birth” (The London Miscellany 8). Reinforcing this theme, the same number of the London Miscellany includes four elaborate pull-out color engravings that preview another Rymer serial, Rich and Poor (nos. 3 and 4), in which stock rich characters economically, sexually, and judicially exploit poor ones, with fatal consequences. These four images are the work of artist Robert Prowse (Adcock), controversial illustrator of Charley Wag, The New Jack Sheppard (1860-1), which builds up to a Tower of London heist (Springhall 62). In the fifth number of The London Miscellany, an anonymous contributor declared that “[h]e who is not angry when injustice is perpetrated against the poor and helpless need not mock Heaven with his prayers; hell is ever waiting for him, and the devil will never be further away than his elbow” (The London Miscellany 69). By making the editorial decision to print this aphorism, Rymer renders acceptance of the socio-economic status quo a danger to the well-off Briton’s soul.

A Mystery in Scarlet

A longing for reform breathes life into the leading (front-page) serial of The London Miscellany, A Mystery in Scarlet. In this serial, Rymer explores anxieties about the perceived relations between gender, householder status, age, and capacity for responsible political participation. For most of Rymer’s lifetime, activists had pursued the expansion of the franchise beyond the male contingent of the socio-economic elite. In 1832, the “Great” Reform Act had admitted to the franchise men who paid homeowner's rates of £10 per annum. This reform increased by five percent the mass of British men eligible to vote, but the change hardly benefited the working class. As an 1840 editorial noted, "less than one in thirty of the entire population” (emphasis original) could vote (Berman). Regions with low property values were hit particularly hard by the property test's quantitative benchmark. For instance, in Leeds, low wages and commeasurately low-cost housing largely priced workers out of the electorate (Briggs 239). The unfinished business of expanding the electorate to genuinely represent the people remained subject to intense debate for the next several decades and was a major pillar of Chartism. Parliament rejected the further expansion of the electorate proposed in three successive successive Chartist petitions (1839, 1842, and 1848). In 1865, a new reform campaign heated up. In 1866, some reformers demanded the extension of the vote to women, inaugurating the campaign for truly universal suffrage that would succeed in 1918. However, as Janice Carlisle observes, in 1866-7, “one question stood out from all others ... how many working-class men--should be added to the electorate?" (Carlisle).

As Katherine Gleadle shows many reformers responded to this question by proposing to extend suffrage only to "the respectable artisan—typically envisaged as a family man and a moral, self-improving citizen” (Gleadle 32). According to this logic, “[t]he ability of the head of the household to provide for his dependents and exert authority over them indicated his capacity for responsible citizenship,” in contrast with the “sexually free bachelor” and the residuum, or supposedly idle poor (Gleadle 32-3). Implicitly, household suffrage disenfranchises most young men and makes political responsibility a condition into which men could mature. For many participants in the debate, this was not reform enough. In February 1866, James Clay, MP for Hull, proposed what colloquially became known as the "Young Men's Bill," which aimed to enfranchise all adult men who could meet an educational qualification, but this bill failed. To many reformers, household suffrage appeared "a realistic compromise compared with [universal] manhood suffrage” (Gleadle 33-4).

”Manhood Suffrage and Vote by Ballot.” [Poster] c. 1866. The People’s History Museum, Manchester, Wikimedia Commons. Used with permission of the People's History Museum.

Therefore, it seems no accident that the name of Rymer's imaginary interlocutor, “Paterfamilias,” aptly describes all three major figures in A Mystery in Scarlet. The title character, protagonist, and villain are all fathers or father-figures, and the novel focuses thematically on the extent to which each rises to or fails at that role. The action begins in the mid-eighteenth century, with King George II inspecting his image, not in a mirror, but in an uncannily mirror-like portrait. In his painted double, the King scrutinizes “a brow so wrinkled and corrugated that it more resembled some strange fabric which had been exposed to the action of fire than any thing human” (The London Miscellany 1). Like Dorian Gray’s portrait half a century later, this Gothic eikon basilike horrifyingly reveals its subject's moral flaws in physiognomic form. Tyrannical, paranoid, avaricious, sexually unfaithful, and consumed with hatred for his suffering queen, Caroline of Ansbach, and ambitious son, Frederick Prince of Wales, George II reassures himself, out loud, that patriotism involves both “service to his king—and—and his country—of course his country” (2). As a father to his own family and the nation, this monarch is a complete failure. While one 1860s opponent of expanded suffrage, Robert Lowe, Viscount Sherbrooke, contended that working-class men gravitated toward wilful ignorance and random violence (Briggs 460), A Mystery in Scarlet suggests that these qualities also distinguish the ancestors of Queen Victoria and her immediate predecessors.

As the plot of A Mystery in Scarlet unfolds, Rymer depicts two disenfranchised men evolving into good father-figures, subjects, and leaders. This process begins when King George orders a loyal Kew Palace guard, Captain Weed Markham, to lead a firing squad. Markham's charge is to execute an unnamed stranger in a scarlet coat, supposedly a dangerous traitor who identifies himself only as “a Mystery in Scarlet” (The London Miscellany 3). Markham obeys the royal order, as he is accustomed to doing. An orphan, Markham has “neither kith nor kin,” is “alone in this wide world” and consequently grateful for the livelihood and purpose his commission provides. However, when the body of the Mystery in Scarlet vanishes and Markham, at the King’s command, endeavors to locate it, he finds that the Mystery is not dead—and is the secret elder half-brother of George II. This secret makes the Mystery Britain’s rightful king, and creates a moral dilemma for Markham. Suddenly finding himself a servant of two royal masters, Markham does not know which to protect or how to act. Struggling with his dilemma, he discerns that his efficacy as a subject is limited by his degree of power. “What should he do?” he wonders:

Or, rather, what could he do?

What was his duty?

And that again resolved itself into, what was his power? (66)

Without “power,” Rymer insists, the British subject is unable to fulfill his patriotic “duty.” Meanwhile, the Mystery charges Markham to protect his daughter Bertha in an explicitly patriarchal way. “[B]e to her that which I would have been,” the Mystery begs (3). Markham tries, but, of course, he falls in love with her. In becoming her guardian, then her husband, the unquestioning career soldier matures into a critically reflexive citizen. In the end, Markham serves his newfound family and his country by rescuing the Mystery while deterring him from violent revolution, a threat underscored by repeated, often ghoulish references to the Civil War and the Regicide. With this resolution, Rymer questions the notion that the ruling elite unquestionably produces good paterfamiliae. Furthermore, as the Mystery in Scarlet is a credible pretender to the British throne, his decree that Markham should protect his daughter and his permission for Markham to marry her makes Markham a citizen by a kind of royal will. This plot point implies that British national destiny requires the enfranchisement of working-class paterfamiliae, including potential paterfamiliae like Markham.

Illustrations

Like practically all the leading serials of the penny magazines and newspapers, A Mystery in Scarlet is lavishly illustrated. It carries seventeen initial illustrations: one per installment with the unexplained exception of the ninth installment. These unsigned plates are the work of the iconic Dickens illustrator "Phiz" (pseudonym of Hablot Knight Browne). How can we tell? Firstly,The London Miscellany credits Phiz as the illustrator of some of the magazine's content. At the end of the first number, a “Notice to Subscribers” announces that “a high class of Illustrations” is assured because “we have made permanent arrangements with PHIZ, and other eminent Artists engaged on Once a Week, Good Words, The Leisure Hour, and other approved serials” (12). In later numbers of The London Miscellany, illustrations of specific fiction titles are credited to Phiz. These titles include the generic ‘urban mysteries’ sketch collection London Revelations, as a note in The London Miscellany, no. 4 declares (44).

More concrete evidence appeared in the Victorian journalist Thomas Power O’Connor's periodical T.P.’s Weekly in 1907. "Malcolm J. Errym ... a transposition of his real surname, Rymer... flourished about half a century ago," O'Connor recalls. "I remember a story of his called "A Mystery in Scarlet," treating of King George II, and the Young Pretender. This was illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot K. Browne), and appeared in The London Miscellany, about 1867" (O’Connor 732). Admittedly, O’Connor was wrong about the Young Pretender (Charles Edward Stuart), but otherwise correctly identifies Rymer, for instance by stating that Errym wrote for Reynolds's Miscellany (732). In the twenty-first century, the penny fiction scholar John Adcock has declared in his blog Yesterday's Papers that Phiz/Browne is the illustrator of A Mystery in Scarlet.

”Phiz” (Hablot K. Browne). “‘By order of the King, fire!’” A Mystery in Scarlet. In The London Miscellany, vol. 1, no. 1 (10 Feb. 1866): 1. Unbound penny number. Courtesy the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.

This attribution makes sense on an aesthetic level. The illustrations of A Mystery in Scarlet look very much like Browne's work. They are rendered in the "comedic and theatrical style" for which he was renowned, and which was largely displaced in the 1860s by a new, more serious mode (Allingham "A Tale"). Several features of the plates echo Browne's earlier works, including his Dickens illustrations. These features include oblong compositions, meticulously detailed eighteenth-century court dress, lines that appear thin for a wood relief print, exaggerated facial expressions, portraits hung in rows above the characters, characters drawn from the back as they wheel dynamically forwards, and crowd scenes in which the crowd appears to have lined up in one or two horizontal rows at the front of the composition. On account of these and other strong stylistic similarities, Phiz's modern biographer Valerie Browne Lester has "no doubt whatsoever" that the artwork of A Mystery in Scarlet is "very obviously by Phiz" (Lester).

The medium of the illustrations is wood engraving. In 1850-1880, at least a quarter of all illustrations printed in British books were durable, inexpensively-produced end-grain wood engravings (Allingham, "Technologies.") Wood engravings were particularly prominent in the penny press. In fact, they had been since the penny press's inception in the 1830s. Rymer seems to have insisted that illustrators of The London Miscellany plan for their drawings to be transferred to wood. In the fourth number, he castigates a correspondent for submitting a drawing for consideration in another medium. “The drawing should have been on wood,” Rymer declares. “If you will send us a block, we shall be able to judge” if it is suitable (64). Evidently, wood engraving was the medium in which The London Miscellany was illustrated.

Nevertheless, Browne found this medium profoundly frustrating. As Rodney K. Engen has documented in his Dictionary of Victorian Wood Engravers, "Browne was never comfortable drawing on wood, his style being too fine-lined and sketchy to be adequately engraved or printed" (34). In 1867, Browne wrote to his son that he was engaged to supply a "Sporting Paper" with drawings on wood. "I hate the process," Browne declared:

It takes quite four times as long on wood--and I cannot draw and express myself with a nasty little finiking brish, and the result when printed seems to alternate between something all as black as my hat--or as hazy and faint as a worn-out plate. (qtd. in Kitton 19)

Still, work was work, and Browne needed work. During the 1860s, he executed at least 227 illustrations that were ultimately printed from wood, including The Young Ragamuffin, which was engraved in 1866 by the firm of George and Edward Dalziel, the "visionary engravers" who in the previous year had brought John Tenniel's Alice in Wonderland illustrations to life (Engen 34-5). Rymer should have been delighted to obtain "Phiz's" collaboration on The London Miscellany. As Allingham has observed of Browne's illustrations of A Tale of Two Cities (1859), those of A Mystery in Scarlet make "characters initially unknown [...] more and more recognizable as a result of an interaction of text and plate, and of the plates with each other" (Allingham, "A Tale.") Stereotyping (in the printing-related sense of that word) the stock characters in the brain, the figures facilitate their instant recall when, after vanishing into the shadows for a few chapters, they reappear.

Browne's contribution to A Mystery in Scarlet also helpfully reinforces Rymer’s political agenda. Privileged villains such as Norris appear comedic figures. In the first illustration, Norris crouches like a lapdog at the heels of the gallant Captain Markham. Court scenes underscore the sumptuous extravagance and frivolous antiquated fashion of early Hanoverian St. James, echoing the class politics of the text. Similarly advancing this rhetoric, Prowse's Rich and Poor prints depict the rich as sybaritic monsters and the poor with dignity. In these prints, Prowse arranges his poor characters in nuclear family compositions. This emphasizes the working-class domestic unit as a locus of virtue, just as does A Mystery in Scarlet.

Copies Consulted and Pictured

Copies of The London Miscellany, volume one (1866), containing the eighteen installments of A Mystery in Scarlet, are scarce but accessible. A bound copy of this volume survives in the collection of the Wells Library at Indiana University, Bloomington. The same university’s Lilly Library possesses additional, unbound copies of the first and eighteenth numbers, containing the first and final installments. The entire first volume and some later numbers of the "new series" (also edited by Rymer) are also in the British Library’s Collection. None of this evidence eliminates the possibility that the serial was issued separately in penny parts that Stevenson might have read. However, unless and until such an edition is located, we must not assume it was ever published. As far as we can now know, the London Miscellany is the serial’s only edition.

The primary text of the present edition is transcribed from the Wells Library copy of the London Miscellany. Most of the engravings (no. 2-17) derive from the Wells Library copy of the London Miscellany. The illustrations of the first and final installments are reproduced from the Lilly Library’s slightly better, near-magically clean unbound copies of those numbers. I reproduce these copies primarily so that readers of COVE without access to the archives and private collections that hold the rare surviving examples of unbound issues or numbers of penny periodicals like The London Miscellany can see what they looked like, and envision taking them down from a Victorian newsagent’s shelf and holding them in their hands. The Lilly copy of The London Miscellany no. 1 is the source of the images of Prowse's "Rich and Poor" prints, another set of which survive in the copy at the British Library.

Editorial Method

The present edition is partly documentary, as it faithfully reproduces the 1866 text, including many of its errors and idiosyncrasies. Like The London Miscellany, I present A Mystery in Scarlet serially, in eighteen installments. Each installment echoes its source by picturing the London Miscellany masthead, initial illustration, and three-chapter text. The text is paginated exactly as in The London Miscellany. This convention accounts for the gaps in the pagination. Each of the eighteen installments is relatively short, totalling approximately 6,000-7,500 words. However, the text will probably occupy a great deal of space on your screen. This effect is primarily due to Rymer’s frequent use of one-sentence paragraphs, a convention that pervades his fiction. While the plentiful line breaks build tension, they also consume column inches quickly, allowing Rymer to fill pages quickly and to write multiple serials at once. I suspect that this generic convention of the penny serial contributes to the scarcity of critical editions, as such a waste of paper and ink does not accord well with the economics of traditional academic print publishing.

To facilitate deep and mindful reading, the most disruptive of the source text's typographical errors are amended and the corrected text marked with square brackets []. Annotations of these bracketed phrases reveal the original, erroneous text. However, other idiosyncrasies of the source are preserved, including the original formatting of the line breaks. The images of the Lilly and Wells copies of The London Miscellany have not been digitally corrected. This choice enables readers to encounter the serial nearly as they might in a physical archive, with the discoloration and damage visually apparent.

To enhance undergraduate comprehension and enjoyment of A Mystery in Scarlet, and to point up important critical and cultural contexts of the work and Rymer's world, the installments are discursively annotated. Many annotations include photographs of material culture. historical figures, and actual landmarks and localities depicted in the text, often with citations helpful for further reading. The annotations are neither numerous nor terribly discursive, intended to enhance deep reading of the main text instead of leading the reader away from it. At the very end of this introduction, I append a family tree illustrating the relationships between the historical and fictional characters of A Mystery in Scarlet. (Warning: it supplies plot spoilers!)

As Linda Hughes has shown, the editors of Victorian periodicals such as The London Miscellany curated them with thematic and ideological relationships between their contents, both within individual numbers and across volumes. This editorial convention invites Victorian consumers and modern critics of periodical writing to "read" periodicals "sideways," or across contents and genres (Hughes 1). To facilitate sideways reading, I provide a brief selection of contents from The London Miscellany that, firstly, appeared in the same numbers (1-18) as A Mystery in Scarlet and, secondly, either engage its preoccupations or shed light on its editor Rymer's sense of himself and his audience. These extracts include the comic dialogue "The Editor and Paterfamilias," the promotional print series Rich and Poor, and "The Barber Fiend," a brief retelling of one of Rymer's key sources for his creation of Sweeney Todd. Readers who wish to access the entire run of The London Miscellany that carries A Mystery in Scarlet, no. 1-18 (1866) may consult Google Books' low-resolution but legible scan of the Wells Library copy.3

"The paradox of periodicals scholarship in the digital age," observes James Mussell, "is that although the print objects are closer to the past, it is by doing things to them--reading them, of course, but also transforming, translating, processing, and reformatting them--that we bring the past closer to us" (Mussell 30). Rymer's ambitions in his writing of serial fiction and editing of penny periodicals such as The London Miscellany encompassed bringing British history closer to the working classes of Britain's major urban centers, a community ripe for intellectual engagement and political self-assertion. These cities include Rymer's beloved London, where he was born and where he spent his entire literary career, and his father's birthplace, Edinburgh, which was also that of Stevenson. It is my hope that the "things" you see "done to" A Mystery in Scarlet here at the COVE will bring that text and its world close to you.

1 Throughout the twentieth century, The String of Pearls was attributed to Thomas Peckett Prest (1810-59) and/or James Malcolm Rymer. As I argue elsewhere, the traditional attribution of The String of Pearls to Prest seems to derive from a speculative quip published in 1892 by George Augustus Sala, who frequently lied (Nesvet 2020). As Helen R. Smith has diplomatically put it, “Sala’s later[-career] recollections require closer examination” than they have received because “they seem designed entirely to amuse,” with no regard for truth (Smith 2019, 46). Today, Smith's bibliographic work (2002) has caused a broad consensus of critics to accept Rymer as the author of The String of Pearls. As Dick Collins (2010), who unearthed further evidence tying the text to Rymer, declares, “the case” for Rymer’s authorship “seems proven” (Collins xiii). More recently, firm attributions to Rymer can be found in Marie Léger-St-Jean’s magisterial bibliographic database Price One Penny: A Database of Cheap Literature, 1837-1860, in Smith's contribution to Lill and Rohan McWilliam's edited volume on Lloyd (especially 39-40), and in other contributions to the same volume by Louis James and Sara Hackenburg. McWilliam discusses The String of Pearls as an “anonymous” work, claiming that it does not matter which of Lloyd’s staffers wrote it because they ultimately answered to him (198), but no recent scholarship makes a positive claim for Prest as the author. Additional primary evidence supporting the attribution to Rymer includes a précis published in Rymer's The London Miscellany (1866) of the 1824 Tell-Tale story universally accepted as a source for The String of Pearls, “The Murders in the Rue de la Harpe,” (“Curiosities of Crime: The Barber Fiend,” in vol. 1, no. 15, 239). It is on all these grounds and others that I accept the attribution of The String of Pearls to Rymer.

2 A penny magazine titled The London Miscellany: of Literature, Science, and Art, was in print in 1857-8 (at minimum). It contains fiction attributed by modern scholars to Rymer. A bound copy of no. 1-32 survives in the collection of the British Library. The 1866 London Miscellany begins with vol. 1, no. 1 and makes no mention of this earlier venture.

3 I am extremely grateful to the Lilly Library for making images of these materials accessible in this open-access edition and for granting me an Everett Helm Short-Term Fellowship in the Spring of 2018. Without the Helm Fellowship, I would not have been able to do the research necessary to compile this edition.

Works Cited

Note: only open-access born-digital electronic sources are hyperlinked.

Adcock, John. “The London Miscellany.” Yesterday's Papers, 21 Jun. 2012.

Allingham, Phillip V. "A Tale of Two Cities (1859): The Last Dickens Novel "Phiz" Illustrated." Victorian Web.

---. "The Technologies of Nineteenth-Century Illustration: Woodblock Engraving, Steel Engraving, and Other Processes." Victorian Web.

“The Barber’s Lesson to his Apprentice.” [illus.] James Malcolm Rymer, The String of Pearls, or, the Sailor’s Gift; a Romance of Particular Interest, plate no. 1. Lloyd, 1850, Wikimedia Commons.

Berman, Carolyn Vellenga. "On the Reform Act of 1832." BRANCH: Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History, edited by Dino Franco Felluga, extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net.

Boone, Troy. Youth of Darkest England: Working-Class Children at the Heart of Victorian Empire. Routledge, 2005.

Breton, Rob. The Penny Politics of Popular Fiction. Manchester UP, 2021.

Briggs, Asa. England in the Age of Improvement, 1783-1867. 1955. Folio Society, 1999.

Brown, Susan, Patricia Clements, and Isobel Grundy. "James Malcolm Rymer." The Orlando Project, Cambridge University, accessed on 4 Aug. 2018.

Buckley, Matthew. "Sensations of Celebrity: Jack Sheppard and the Mass Audience." Victorian Studies , vol. 44, no. 3, 2002, pp. 423-463.

Carlisle, Janice. “On the Second Reform Act, 1867.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History, edited by Dino Franco Felluga, extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net.

Collins, Dick, ed., James Malcolm Rymer: The String of Pearls (Sweeney Todd). Wordsworth, 2010.

Engen, Rodney K. Dictionary of Victorian Wood Engravers. Chadwyck-Healey, 1985.

Flanders, Judith. “Penny Dreadfuls.” The British Library, 2014.

Frost, Thomas. Forty Years' Recollections: Literary and Political. Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington, 1880.

—. Reminiscences of a Country Journalist. Ward and Downey, 1886.

Geier, Ted. Meat Markets: The Cultural History of Bloody London. Edinburgh UP, 2017.

Gleadle, Katherine. “Masculinity, Age, and Life Cycle in the Age of Reform.” Parliamentary History, vol. 36, no. 1, 2017, pp. 31-45.

Hackenberg, Sara. “Romanticism Bites: Quixotic Historicism in Rymer and Reynolds.” Edward Lloyd and his World: Popular Fiction, Politics, and the Press in Victorian Britain, edited by Sarah Louise Lill and Rohan McWilliam, Routledge, 2019, pp. 165-182.

Haywood, Ian. The Revolution in Popular Literature: Print, Politics, and the People 1790-1860. Cambridge UP, 2004.

Hughes, Linda K. "Sideways!: Navigating the Material(ity) of Print Culture." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 47, no. 1 (2014): pp. 1-30.

James, Louis. "'I am Ada!' Edward Lloyd and the Creation of the Victorian 'Penny Dreadful'. Edward Lloyd and His World: Popular Fiction, Politics and the Press in Victorian Britain, edited by Sarah Louise Lill and Rohan McWilliam, Routledge, 2019, pp. 54-70.

—. Fiction for the Working Man, 1830-50. 3rd ed. Edward Everett Root, 2017.

—. “Rymer, James Malcolm.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 60 vols. Oxford UP, 2004, vol. 48, pp. 494-5.

“James Malcolm Rymer, The Dark Woman” [catalog entry]. Richard Neylon, St. Mary's, Tasmania, Australia, accessed on 12 Mar. 2018.

Kitton, Frédéric George. "Phiz" (Hablot K. Browne), A Memoir, Including a Selection from his Correspondence and Notes on His Principal Works. Satchell, 1882.

Léger-St. Jean, Marie. Price One Penny: A Database of Cheap Literature, 1837-1860. 29 Jun. 2019. Faculty of English, Cambridge University. 4 Mar. 2020.

Lester, Valerie Browne, email to Rebecca Nesvet, 4 Aug. 2018.

Lill, Sarah Louise. “Romances and Penny Bloods.” Edward Lloyd.

The London Miscellany, ed. James Malcolm Rymer. Charles Jones, 1866, vol. 1, no. 1-18.

The London Miscellany, vol. 1, no. 1-32, 1857-8.

”Manhood Suffrage and Vote by Ballot.” [Poster] c. 1866. The People’s History Museum, Manchester, Wikimedia Commons.

McWilliam, Rohan. "Sweeney Todd and the Chartist Gothic: Politics and Print Culture in Early Victorian Britain." Edward Lloyd and His World: Popular Fiction, Politics and the Press in Victorian Britain, edited by Sarah Louise Lill and Rohan McWilliam, Routledge, 2019, pp. 198-215.

Mehew, Ernest, ed. Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. Yale UP, 1997.

Mussell, James. "Beyond the 'Great Index': Digital Resources and Actual Copies." Journalism and the Periodical Press in Nineteenth Century Britain, edited by Joanne Shattock. Cambridge UP, 2017, 17-30.

Nesvet, Rebecca. "The Bank Nun's Tale: Financial Forgery, Gothic Imagery, and Economic Power." Victorian Network, vol. 8 (2018): 29-50.

—. "Blood Relations: The Spaniard and Sweeney Todd," Notes and Queries, vol. 64, no. 1, 2017, pp. 112–16.

—, "The Mystery of Sweeney Todd: G.A. Sala's Desperate Solution." Victorians Institute Journal, vol. 47 (2019-20): 11-35.

—, ed. “Science and Art: A Farce in Two Acts, by Malcolm Rymer.” Scholarly Editing: The Annual of the Association for Documentary Editing, vol. 38, no. 1, 2017.

O’Connor, Thomas Power. “Author Found.” T.P.'s Weekly, vol. 9, 7 Jun. 1907, p. 732.

“Parties for the Gallows.” Punch vol. 8, 1845, p. 187. Google Books.

“Phiz” (Hablot K. Browne). “‘By Order of the King, Fire!’” A Mystery in Scarlet, plate no. 1. In The London Miscellany vol. 1, no. 1, 10 Feb. 1866, p. 1.

The Queen’s Magazine, ed. James Malcolm Rymer, vol. 1, no. 1-5, 1842.

—. Mazeppa, or, the Wild Horse of the Ukraine. London: Edward Lloyd, 1850.

Smith, Helen R. “Edward Lloyd and his Authors.” Edward Lloyd and his World: Popular Fiction, Politics, and the Press in Victorian Britain, edited by Sarah Louise Lill and Rohan McWilliam, pp. 39-53. Routledge, 2019.

Stevenson, Robert Louis. “Popular Authors.” Scribner's Magazine, 7 Mar. 1888, pp. 122-8.

Sutherland, James. A Book of Scattered Leaves: Poetry of Poverty in Broadside Ballads of NIneteenth-Century England, 2 vols. Bucknell UP, 2002.

—. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction, 2nd ed. Routledge, 2013.

Springhall, John. Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics: Penny Gaffs to Gangsta-Rap, 1830–1996. Macmillan, 1999.

Tillotson, Katherine. Novels of the Eighteen-Forties. Clarendon, 1954.

Twelfth Report of her Majesty's Civil Service Commissioners, vol. 21. Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1867.

Thompson, Dorothy. Outsiders: Class, Gender, and Nation. Verso, 1993.

Vanden Bossche, Chris R. “On Chartism.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History, edited by Dino Franco Felluga, extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net.

Wester, Maisha. “Text as Gothic Murder Machine: The Cannibalism of Sawney Beane and Sweeney Todd.” Technologies of the Gothic in Literature and Culture: Technogothics, edited by Justin Edwards, Routledge, 2015, pp. 154-65.

Family Tree of Historical and Fictional Characters