Purdue Honors College Leonardo da Vinci Timeline

Created by Dino Franco Felluga on Thu, 01/25/2018 - 15:48

Part of Group:

This timeline, tied to HONR 299: Leonardo da Vinci at Purdue University, explores various aspects of Leonardo's career, as well as the transition from the medieval period to the Renaissance (and beyond).

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1476 |

Missale Romanum, Ulrich Han

Missale Romanum was the first book of music to be printed using movable type, which was invented in China around 1401. Missale Romanum contained only monophonic music, but its publication is still significant because it revolutionized printing techniques. There are many nuances associated with printing music; first, the printer would need to establish the set of immovable lines that makes up the staff. Second, the printer would need to accurately superimpose all other musical notations on top of the staff. The creation of a method that factored these into account led to the bulk printing and distribution of music, as seen by Ottaviano Petrucci’s Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, which was the first music book to be printed in extensive quantities, as well as the first polyphonic book printed using movable type. As bulk printing gained momentum, music was easily distributed across cities and countries, and it became more universal and accessible.

Sources:

- Norman, Jeremy. “Ulrich Han Issues the First Dated Printed Book Containing Music (October 12, 1476).” Ulrich Han Issues the First Dated Printed Book Containing Music (October 12, 1476) : HistoryofInformation.Com, Jeremy Norman and Co., Inc., 29 Jan. 2015, www.historyofinformation.com/expanded.php?id=3741.

Image Source: http://www.musicprintinghistory.org/music-type/moveable-type |

Jennifer Liu | ||

| circa. 1478 to circa. 1519 |

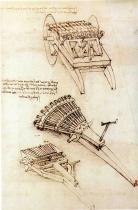

Da Vinci's CannonsLeonardo Da Vinci was living in a world engulfed in war, having been born just after the Hundred Year's War, and living through the beginning of the Spanish Italian Wars in 1494. As a self-proclaimed weapons designer, Da Vinci was fascinated with improving upon and developing new ways to destroy an enemy. In his notebooks, there are over 10 designs for different siege weapons, cannons, and guns, many of which are reproduced and on display in Italy, designed from the original sketches in the Codex Atlanticus. Such weapons include his three-barreled cannon, 33-barreled organ, and his varieties of elevating gear cannons. The primary focus of these weapons was to inflict as much damage possible through a machine that was easier to operate and more effective than previous light artillery of the time. For example, the Da Vinci Museum of Science and Technology describes his triple barrel cannon as being, "...a different specimen of light artillery: the gun carriage is easy to handle and it has three front-load guns. To improve firing accuracy, the three guns can be adjusted in height by means of a peg mechanism. (The Collection of Models)" This type of adjustment and agility is revolutionary in that it allows the user to not only fire 3 shots at once, but also be able to precisely aim without a team of multiple men. His two very similar single barrel cannon designs also involve a precise aiming system of either pegs or screws. Sources: John. “Bensozia.” Leonardo's Cannon, 1 Jan. 1970, benedante.blogspot.com/2011/06/leonardos-cannon.html. in History, Technology | April 7th, 2016 3 Comments. “Leonardo da Vinci Draws Designs of Future War Machines: Tanks, Machine Guns & More.” Open Culture, www.openculture.com/2016/04/leonardo-da-vinci-draws-designs-of-future-wa.... “Triple Barrel Canon.” Leonardo da Vinci's Triple Barrel Canon Invention, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/triple-barrel-canon.aspx. “The collection of models.” The collection of models - museoscienza, www.museoscienza.org/english/leonardo/models/. |

Steven Mazzochi | ||

| 1478 to 1480 |

Self-Propelled CartLeonardo da Vinci conceptualized the idea for a self-driving cart many centuries before automobiles or robotics. In fact, a working model of da Vinci's design was created by modern scientists in 2006 at Italy's Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence, according to an ABC News article (see source below). Incredibly enough, the prototype was successful in moving without being pushed. Da Vinci’s design used coiled springs, and had both steering and brake capabilities. It was designed to operate autonomously, with wound-up springs rotating the wheels of the cart after a brake was released. Prior to movement, the cart could be adjusted such that it would travel in any direction based on if the steering was set at any preset angles. According to the same ABC News article, researchers at the Armand Hammer Center for Leonardo Studies in Los Angeles (see source below) said da Vinci's design has many similarities to the Mars Rover, a vehicle capable of autonomous travel on the surface of Mars. Many people today believe da Vinci’s self-propelled cart to be the world’s first robot.

Sources: “Self-Propelled Cart.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Self-Propelled Cart Invention, 2008, http://www.da-vinci-inventions.com/self-propelled-cart.aspx. Lorenzi, Rossella. “Da Vinci Sketched an Early Car.” News in Science, 2004, www.abc.net.au/science/news/stories/s1094767.htm. Image Source : xiquinhosilva (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_Vinci_Self_Propelled...), "Leonardo da Vinci Self Propelled Cart", https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| circa. 1478 to circa. 1480 |

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Madonna of the CarnationLeonardo Da Vinci’s Madonna of the Carnation is currently displayed in the Alte Pinakpthek gallery in Munich, Germany. This rendition of the Madonna and Child was originally thought by art historians to have been painted by Andrea del Verrocchio; however, it is now agreed that Da Vinci created this piece. An oil painting on panel, the Madonna of the Carnation made use of a new medium of the Renaissance. This painting depicts Mary sitting with an exceedingly chubby and somewhat disproportionate baby Jesus on her lap. She holds a carnation, a symbol of healing, in her left hand. Da Vinci illuminates the faces of Mary and the Child but darkens the background through shadowing using the technique of chiaroscuro, which he later masters. The baby Jesus is looking upwards while Mary is looking down – neither are looking at the other. The folds and shadowing of their clothes are suggestive of depth, and the background of mountains and the blue sky adds to this feeling as the background becomes blurred in the distance, melding into the horizon.

Sources Used: Feinberg, Larry J. “Sight unseen: vision and perception in Leonardo’s Madonnas: in the first of two articles on Leonardo da Vinci, Larry J. Feinberg explains how the artist’s interest in the way the eyes work influenced his realistic depictions of the Christ Child as a baby learning to see.” Apollo 159.509 (2204): 28-34. GALE. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. “Madonna of the Carnation.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Nov. 2016. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. Image Courtesy of Wikipedia, page titled Madonna of the Carnation. Image is Public Domain. |

Alicia Geoffray | ||

| 1478 to 1518 |

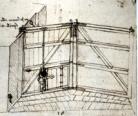

Codex Atlanticus & Da Vinci’s Hoist MachinesThe Codex Atlanticus is a collection of twelve notebooks containing a compilation of sketches and writings by Da Vinci collected by Pompeo Leoni. The topics of the codex range across a variety of subjects, from science and technology to town planning to music. Within the codex are drawings of several machines for lifting an moving heavy weights including hoist and crane mechanisms. It is suspected that Da Vinci’s drawing of these machines may be based off the mechanisms designed by Brunelleschi during the construction of the Florence Duomo which were used by Verrocchio during the time Da Vinci worked in his studio. “Codex Atlanticus.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Atlanticus. “LEONARDO DA VINCI - Codex Atlanticus.” Museo Galileo: Institute and Museum of the History Ans Science, brunelleschi.imss.fi.it/genscheda.asp?appl=LIR&xsl=manoscritto&lingua=ENG&chiave=100776. Image Courtesy of: Museo della Scienza e della Tecnologia "Leonardo da Vinci" [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

Stephanie Andress | ||

| circa. 1480 to circa. 1500 |

Leonardo da Vinci and the SunLeonardo da Vinci’s fascination with space and nature was not limited to the moon, or even a specific celestial body. While da Vinci had a keen interest on the moon and focused quite heavily on its physical properties, he had devoted a vast amount of time to exploring the movements and nature of the solar system we reside in. His immense amount of intellectual curiosity led to one of his most significant discoveries, the lack of movement of the sun. He stated in his notebook “IL SOLE NO SI MUOVE,” which translates to “the sun does not move.” In addition to this statement, he concluded that the earth is not the center of the circle of the sun, nor is it the center of the universe. It is unclear if these thoughts were shared with others or if they just remained in his notebooks for only Leonardo to view. It is obvious that these insights were much too advanced for da Vinci’s time, like many of his other accomplishments and inventions. With this in mind, if he had shared his ideas, they most likely would have been rejected and forgotten only to be proved correct 40 years later by a man named Nicolaus Copernicus. Today, Copernicus is considered to be the astronomer that discovered the sun’s apparent lack of movement. Sources: "Leonardo da Vinci." Giants of Science. https://careers.knoji.com/the-major-accomplishments-of-leonardo-da-vinci/. Accessed 28 Feb. 2018. "I Leonardo." Ralph Steadman Art Collection. Public Domain. http://www.ralphsteadmanartcollection.com/collection-view.asp?collection.... Accessed 28 Feb. 2018. |

Rachel Lee | ||

| circa. 1480 |

The Ideal City (Paintings)The Ideal City is the name given to three strikingly similar paintings that show some of the ideals of Italian Renaissance work. They demonstrate a respect for Greco-Roman antiquity, ideals of city planning, and show mastery of central perspective. The Ideal City of Baltimora is done by Fra Carnevale and includes an amphitheater that resembles the Roman Colosseum. On the opposite side of the painting, an octagonal building with a steeple on top suggests the medieval Baptistry in Florence. The two buildings reflect the values of security, religion, and recreation as well as the emphasis on Roman ideas in new, ideal urban designs. The illusion of space is achieved using the receding lines that converge at a center point in the city. Sources: “The Ideal City.” The Walters Art Museum, art.thewalters.org/detail/37626/the-ideal-city/. Onniboni, Luca. “The "Ideal City" in three Renaissance paintings.” Archiobjects, 18 Nov. 2014, archiobjects.org/the-ideal-city-in-three-renaissance-paintings/. Image Source: The Walters Art Museum, http://art.thewalters.org/detail/37626/the-ideal-city/ |

Laila Kassar | ||

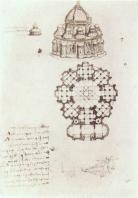

| circa. 1480 |

Central Plan ChurchesAlthough there is no evidence that any of Da Vinci’s church designs were actually constructed, he sketched many floorplans and elevations in his notebooks. Most of these sketches experimented with a central-plan design, where all outside rooms were centered around a main room. His church floor plans usually featured a square or circular center room with semi-circle or square rooms surrounding them. Da Vinci utilized his mathematical background profusely in his floor plans, experimenting with the proportions of each room as well as symmetrical and asymmetrical designs. In one of his prominent designs, a Greek cross with equally sized legs outlined the center of the church used for mass. Many of Da Vinci’s sketches were done in the 1480s, and were probably influenced by Filippo Brunelleschi, a prominent Italian architect who also used central-plan designs in his churches. Sources: Xavier, Joao. “Leonardo’s Representational Technique for Centrally-Planned Temples.” Reasearch Gate, Jan. 2008, www.researchgate.net/figure/Leonardo-da-Vinci-Drawing-of-churches-MS-BN-.... Phillips, Cynthia. “101 Things You Didn't Know about Da Vinci.” Google Books, books.google.com/books?id=qvpFDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA106&lpg=PA106&dq=da%2Bvinci%2Bchurch%2Bcross%2Bdesign&source=bl&ots=XuVDtCOeBM&sig=c47NhxgS09TO-7bLu4KRTIH3Cyk&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjykczD5NjZAhXC7oMKHQ9ZAN0Q6AEIPzAH#v=onepage&q=da%20vinci%20church%20cross%20design&f=false. Teodoro, Francesco Di. “Leonardo Da Vinci: The Proportions of the Drawings of Sacred Buildings in Ms. B, Institut De France.” Architectural Histories, Ubiquity Press, 7 Jan. 2015, journal.eahn.org/articles/10.5334/ah.cf/. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons: |

Scott Lenz | ||

| 1481 |

Linear PerspectiveDuring the Renaissance in Italy, artist and architects sought to understand how to more accurately portray three dimensional objects in a flat plane. This led to the development of linear perspective, a system of creating the illusion of depth through the use of lines that converge at a single vanishing point on the horizon line. As an apprentice in Andrea del Verrocchio’s studio, Leonardo was introduced to the rules of perspective through De Pictura, a treatise on perspective written by the Italian architect Leon Battista Alberti in 1435. One of the clearest uses of linear perspective in Renaissance art is seen in da Vinci’s perspectival study for The Adoration of the Magi. This piece reflects da Vinci’s approach to creating a three-dimensional space on a flat plan and demonstrates his mastery of linear perspective. Sources Blumberg, Naomi. “Linear Perspective.” Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. , 17 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/art/linear-perspective. “Da Vinci - The Artist: A True Master of His Craft.” Museum of Science, Museum of Science, Boston, 2018, www.mos.org/leonardo/artist. Image Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, fair use |

Lauren Krieger | ||

| 1481 |

33-Barreled OrganThe modern machine gun stems from Leonardo da Vinci’s concept of the 33-barreled organ. He saw there was an issue with the current cannon technology, in that they took forever to reload and often misfired. His design incorporated 33 smaller guns connected in three sets of 11 guns that were on a rotating platform. After one set of small cannons were fired, the platform could be rotated to the next set, and so on and so forth. At any point in time, one set could theoretically be firing, one set could be cooling from having just been fired, and one set could be reloaded by soldiers. This increased the overall rate of firing from the weapon, which is why it is considered the predecessor to the modern machine gun. Other designs by da Vinci included having cannons fire in a triangular spread to increase the hit area for the artillery fire. The 33-barreled organ was called as such because the adjacent barrels of the cannons looked very similar to the pipes of an organ.

Sources: “33-Barreled Organ.” Leonardo Da Vinci's 33-Barreled Organ Invention, 2008, http://www.da-vinci-inventions.com/33-Barreled-Organ.aspx. “33-Barrelled Organ.” Museoscienza, 2018, www.museoscienza.org/english/leonardo/invenzioni/organo33.asp. Image Source : Leonardo da Vinci (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ribauldequins_-_Leonardo_da_Vinc...), "Ribauldequins - Leonardo da Vinci studies", marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Template:PD-old. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| 1482 to 1519 |

OrnithopterLeonardo Da Vinci was very interested in the possibility of flight for humans, which explains his extensive study on birds and their ability to fly. This was highlighted through his Codex of Flight of Birds. Though there were extensive drawings on a human-powered flying contraption, called the Ornithopter, Da Vinci soon came to the conclusion that humans themselves were not powerful enough to support the lift-off of the machine nor were they strong enough to support the machine through the flight. However, the device in itself was brilliant because it modeled the human to be positioned such that center of gravity would enable flight and the wings flapped using a pedal, rod, and pulley system. Lastly, we believe that the machine was also extensively tested for flight, through evidence from his associates however there is no evidence of the creation of the machine itself. Sources:- “Flying Machine.” Leonardo da Vinci's Flying Machine Invention, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/flying-machine.aspx. FLYING MACHINES - Leonardo da Vinci, www.flyingmachines.org/davi.html. Fuller, John. “Top 10 Bungled Attempts at One-Person Flight.” HowStuffWorks Science, HowStuffWorks, 8 Mar. 2018, science.howstuffworks.com/transport/flight/classic/ten-bungled-flight-attempt2.html. Image Courtesy:- Wikimedia Commons, public domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Design_for_a_Flying_Machine.jpg |

Yamuna Ambalavanan | ||

| 1483 |

Aerial ScrewOver two thousand years ago, tops consisting of a propeller affixed to a stick were created in China. By using one’s hands to spin the stick, the propeller could achieve lift and hover through the air for a short period of time. This basic concept is reflective in today’s modern helicopters. Leonardo da Vinci sketched designs for his own version of a flying machine, but unfortunately his concept has been determined by modern scientists to not work. This is in part due to him never actually building and testing his idea. However, the concept of using lift to carry a contraption through the sky was still revolutionary. The description "If this instrument made with a screw be well made – that is to say, made of linen of which the pores are stopped up with starch and be turned swiftly, the said screw will make its spiral in the air and it will rise high" was included next to the sketch of da Vinci’s helicopter. It was comprised mostly of a device meant to compress air in order to generate lift- the aerial screw or helical air screw. At full size, da Vinci imagined up a helicopter of over 15 feet in diameter, built out of reed, linen, and wire, which was to be powered by four men turning cranks to rotate a central shaft that turned the aerial screw. In 1796, Sir George Cayley was able to build his own version of a helicopter machine that was powered by elastic devices. Later on, in 1842, W. H. Philips developed a steam-driven model helicopter. All of these incredible designs followed the same principles of generating lift.

Sources: “Helicopter (Aerial Screw).” Leonardo Da Vinci's Aerial Screw Invention, 2008, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/aerial-screw.aspx. “Early Helicopter History.” Aerospaceweb.org, 2012, www.aerospaceweb.org/design/helicopter/history.shtml. Image Source : Permission granted to share this work by Clay Shonkwiler under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_Vinci_Tank_Aerial_Sc...), "Leonardo da Vinci Tank Aerial Screw" https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| 1483 to 1486 |

AnemometerThe usage of simple instruments to indicate the direction of the wind has been known since before the Middle Ages. Leon Battista Alberti developed the anemometer in 1450 to measure wind velocity. However, Leonardo da Vinci redesigned the device, making it more accurate and easier to measure wind force. The anemometer functions because a piece of wood is attached to a frame and gets raised by the wind flowing across the contraption. A scale is labeled on the frame and based on the highest location achieved by the moving piece of wood, a relatively accurate measurement of wind force can be determined. Later versions of the anemometer included applications of fluid dynamics, where wind pressure resulted in a liquid column travelling up a tube and the distance traveled being related to wind force. Another style of anemometer by Thomas Robinson in 1845 included a revolving contraption that spun freely in the wind and wind velocity being able to be determined based on the number of revolutions per unit of time.

Sources: “Anemometer.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Anemometer Invention, 2008, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/anemometer.aspx. “Windvanes and Anemometers.” Multimedia Catalogue, 2010, https://brunelleschi.imss.fi.it/museum/esim.asp?c=500005. Image Source : Permission to use by Fondazione Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci - via San Vittore, 21 - 20123 Milano (Italia). “Anemometer - Leonardo Da Vinci.” Museoscienza, 2018, www.museoscienza.org/english/leonardo/models/macchina-leo.asp?id_macchina=20. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| 1483 |

ParachuteThe first practical device that demonstrated the principle of parachuting was developed by Sebastien Lenormand in 1783. Jean Pierre Blanchard actually created the first parachute in 1785, while Jacques Garnerin was able to make a successful descent with a parachute from 3,000 feet in 1797. All of these iterations were steps towards the modern parachute of today, used by both the military and recreational users- for safety and for fun. The origin of all of this was in Leonardo da Vinci’s parachute design comprised of sealed lined cloth held by assorted wooden poles. In his notebooks, next to his original parachute design, were the words "If a man is provided with a length of gummed linen cloth with a length of 12 yards on each side and 12 yards high, he can jump from any great height whatsoever without injury." This parachute was particularly of note because it had a triangular canopy rather than a rounded one. Modern scientists were skeptical of da Vinci’s parachute being able float, until Adrian Nicholas tested a prototype built to da Vinci’s specifications at 3,000 feet in 2000 and proved it to be successful.

Sources: “Parachute.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Parachute Invention, 2008, http://www.da-vinci-inventions.com/parachute.aspx. “DaVinci's Parachute.” Flying out of This World, 2008, www.flyingoutofthisworld.blogspot.com/2008/02/davincis-parachute.html. Image Source : Permission granted to share this work by Nevit Dilmen under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_Vinci_parachute_0465...), "Leonardo da Vinci parachute 04659a", https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/legalcode |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| 1483 to 1486 |

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Virgin of the RocksLeonardo Da Vinci named two of his paintings the Virgin of the Rocks, and these paintings both depict the Madonna and Child with only a few significant details altered. The earlier version is displayed in the Louvre in Paris while the later version hangs in the National Gallery in London. They are both around the same size, 2 meters, and the are both painted using oil on wooden panels, though the version hanging in the Louvre has since been transferred to a canvas. Both paintings depict the Madonna and Child alongside an angel and an infant John the Baptist. The rocky landscape lends to the title of the two pieces. The paintings differ in a variety of minor ways including the techniques of color, lighting, and sfumato. The version hanging in the Louvre is generally considered the earlier painting, and it was likely painted from around 1483 to 1486. This version is regarded as a perfection of the sfumato technique which Da Vinci is known for. The version hanging in London has a less precise date ascribed to it, but it was likely painted before 1508. The main differences between the two paintings are the positioning of the angel, the coloring of the robes, the halos (or lack thereof), and the staff of John the Baptist (or lack thereof).

Sources used: Pizzorusso, Ann. "Leonardo's Geology: The Authenticity of the 'Virgin of the Rocks.'" Leonardo 29.3 (1966) 197-200. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. “Virgin of the Rocks.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Feb. 2018. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. Image Courtesy of Wikipedia, page titled Virgin of the Rocks. Image is Public Domain. |

Alicia Geoffray | ||

| 1485 |

Redesign of MilanIn 1485, Da Vinci outlined his idea of an “ideal city”. This was a large departure from the previous Medieval cities in Italy, where the city grew naturally and there was no set plan for the locations of waterways or streets. During the plague, almost a third of Milan’s population was killed, so Leonardo wanted to redesign Milan in a way that would reduce the spread of disease and promote efficiency of getting from one place to another. His design featured two separate levels, a lower level of canals for moving goods and common folk, and an upper level for “gentlemen”. To mitigate the chance of another widespread disease impacting the city, Da Vinci planned for the lower level to have a sewer system and the roads on the upper level to be wider than Milan’s very narrow streets so people wouldn’t be as packed together. With regard to the movement of people around the city, he envisioned large wagons and carriages using the lower level streets, making it easier for people on foot to get around on the upper level. Due to the cost of completely rebuilding Milan, Da Vinci’s ideal city was never constructed. Sources: “The Ideal City.” The Ideal City - Leonardo Da Vinci - Museoscienza, www.museoscienza.org/english/leonardo/models/macchina-leo.asp?id_macchin.... “Ideal City.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Ideal City Invention, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/ideal-city.aspx. Image Source: Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Projekt_idealnego_miasta.gif |

Scott Lenz | ||

| 1486 |

Giant CrossbowLeonardo da Vinci is widely known for his many engineering designs centuries before anyone else came up with similar ideas. He was a respected artist and inventor, but also was a gifted military engineer. Something that he really understood was the psychological impact of weaponry. Da Vinci came up with several versions of a giant crossbow, comprised of winding gears similar to the compound longbow of today. When his sketches came to life on the battlefield, they spanned 27 yards across. Each device had six wheels for stability and mobility, and the crossbow itself was made of thin, flexible wood. Priming the giant crossbow involved cranking back various gears and loading up the artillery, and any projectile was launched by releasing a holding pin by striking it with a mallet. The crossbow invention appeared to be made to launch large stones or flaming bombs rather than oversized crossbow bolts, which makes it clear that da Vinci meant for this military invention to cause fear amongst enemies rather than merely inflict mass damage and chaos.

Sources: “Giant Crossbow.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Giant Crossbow Invention, 2008, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/giant-crossbow.aspx. “Leonardo - Giant Crossbow.” BBC Science & Nature, 2014, www.bbc.co.uk/science/leonardo/gallery/crossbow.shtml. Image Source : Leonardo da Vinci (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_vinci,_Giant_Crossbo...), "Leonardo da vinci, Giant Crossbow", marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Template:PD-old. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| circa. 1487 |

Vitruvian ManOne of Leonardo Da Vinci’s most well known pieces of work is his depictions of the Vitruvian Man. Originally theorized by Vitruvius, Leonardo depicts the mathematical formula Vitruvius discovered for the proportions of the human body. The figure is idealized and a depiction of humanistic ideology. Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man applies the perfection of divinity onto a human effectively shifting the limit of perfection away from anagogic space. He places his Vitruvian man in both anagogic and earthly space by placing the figure in both a square (earth) and a circle (anagogic space). By Da Vinci doing this he again places a human figure into anagogic space eliminating the bridge between anagogic and earthly space.

Source and Image Source: Crothers, Laura. Vitruvian Man Had a Hernia. Slate. February 17, 2014,http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2014/02/vitruvian_man_s_hernia_leonardo_da_vinci_drawing_shows_flaws_of_human_evolution.html. Accessed March 8, 2018. |

Amanda Gozner | ||

| 1488 |

Da Vinci's Ideal CityLeonardo was known to dislike the state of urban living, describing cities as old fashioned, where people lived crammed together "like a herd of goats." After Filarete's project Sforzinda, Leonardo was also fascinated by the idea of creating a complex, perfect city. The design combines Da Vinci's wide range of talents, and shows his mastery of architecture, engineering, and art. The phrase ideal city refers to perfection of the 'machinery' of the city. His design utilized his invention of locks to make waterways efficient while keep the city's inhabitants safe from violent floods of water. There was also a strong emphasis on hygiene in his design, which included mechanisms for keeping the streets clean as well as preventing water and waste to stagnate. Da Vinci mentions that he believes the city should be cleaned at least once a year. His city's transportation network included different level streets for different purposes of transportation. Overall, his design focused on the possibilities of geometrically perfect solutions to the predicaments of urban life. Sources: “The ideal city – Ms B Fol 16r and 37.” Universal Leonardo, University of Arts, London, www.universalleonardo.org/work.php?id=519. “The Ideal City.” Museoscienza, Museo Nazionale della Scienza e della Technologia "Leonardo DaVinci", www.museoscienza.org/english/leonardo/invenzioni/citta.asp. Image Source: "The Ideal City", www.leonardo3.net

|

Laila Kassar | ||

| circa. 1489 to circa. 1490 |

Lady with an ErmineOne of the most distinct changes art experienced in the renaissance was an evolution in the purpose it served. During the medieval period, the purpose of art was to educate viewers about religion as well as serving as a form of worship. The population during this time was largely illiterate and had very limited access to religious texts, which meant that a visual representation enabled the viewers to directly connect with and worship their religious icons. Artwork in the renaissance, on the other hand, was more concerned with the aesthetics rather than the religious symbolism that it represented. This is due in part to the rise of humanism which led to an emphasis on the secular ideals of Greek and Roman thought. This painting, Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci, is a perfect example of this. The purpose of this painting is entirely secular; it is celebrating the talent of the artist in portraying the beauty and purity of a noblewoman. Such a show of status and wealth would have been considered hubris during the middle ages but in reality, marked the beginning of a new era in art history.

Sources Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael W. Cothren. Art History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2011. Print. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. “Lady with an Ermine.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 6 Mar. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lady_with_an_Ermine. Image Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, fair use

|

Lauren Krieger | ||

| circa. 1490 |

Leonardo Da Vinci’s Madonna LittaLeonardo Da Vinci’s Madonna Litta is currently housed in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia. This painting depicts Mary holding Christ as he is breastfeeding. In his left hand the baby Christ holds a little goldfinch which is representative of his future Passion. The painting is within an architectural space which has two arched windows in the background. There is little light within the painting (possibly an attempt towards mastering the technique of chiaroscuro) which make the blue background outside of the windows even more apparent. The windows also display Da Vinci’s technique of sfumato, which allows for a more realistic depth of background in which further away objects become less distinct and blend into the horizon. This painting has been attributed to Da Vinci because within his Codex Vallardi, which is currently housed in the Louvre, there is a metal point drawing of a woman’s face in a near profile which is exceedingly similar to the woman’s face in the Madonna Litta. Sources Used: Clark, Kenneth. "The Madonna in Profile." The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 62.360 (1933): 136–140. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. “Madonna Litta.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Dec. 2016. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia, page titled Madonna Litta. Image is Public Domain. |

Alicia Geoffray | ||

| circa. 1490 to circa. 1519 |

Leonardo's Water WheelLeonardo also devised a water wheel. It combines elements of the more effective overshot water wheel with the more conventional water wheel. Here water falling from an aquifer would turn a wheel, which would then turn the blades of a large screw. In this sense, the invention would generate power. However, as water would need to be conveyed up to his aquifer, it was still reliant on human energy. While not practical, the invention makes important theoretical progress. That the wheel is not connected to a millstone, shows Leonardo’s fascination with water and his desire to use it in ways not previously conceived of. He called water the “driver of nature.” He imagined using water to power various processes, including in this case, a drill, possibly in an urban environment. This invention could be seen as a precursor to the modern water turbine. Cooper, Margaret. "The Inventions of Leonardo Da Vini." New York: The MacMillan Company, 1965. Image From: http://www.sussexvt.k12.de.us/science/The%20History%20of%20the%20World%2...'s%20Water%20Wheel.htm (Fair use) |

Ian Campbell | ||

| 1491 |

Fasiculus MedicinaeFasciculus Medicinae is considered the first printed illustrated medical book. It was published in 1491 by a printing company in Venice. The author of the book is Johannes de Ketham. The book is a compliation of multiple essays written about clinical medicine. 8 subjects are discussed in Fasciculus Medicinae: urine and uroscopy, phlebotomy, judgements of the veins, phlebotomy based on the zodiac, women’s health, surgery, and anatomy. The book contains six woodcut illustrations. The first edition of the book was in Latin and a second edition was translated into Italian and then into vernacular Italian in 1493. Leonardo Da Vinci used the Italian edition of Fasciculus Medicinae as a guid during his dissections and as a source of medical knowledge. Fasciculus Medicinae would be further edited through time to improve illustrations and organization. In addition to this more essays and four new illustrations would be added.

Source: Dimaio, Salvatore, Federico Discepola, Rolando F. Del Maestro. Il Fasciculo Di Medicina of 1493: Medical Culture Through the Eyes of the Artist. Neurosurgery 2006, 58:187-196. DOI:10.1227/01.NEU.0000192382.37787.80. Accessed March 8, 2018.

Image Source: Wikipedia

|

Amanda Gozner | ||

| circa. 1493 to circa. 1497 |

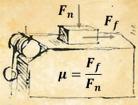

Coefficient of Friction & WearSome of da Vinci’s early work in bearing design centered on the shortcomings of existing designs. He began his work with a series of studies exploring the interaction between objects in contact with one another. The experimental equipment da Vinci designed was an innovation in and of itself. Da Vinci studied what factors contributed to friction and correctly concluded that friction is influenced not only by the types of materials in contact, but also the contact area of the two objects. To decrease friction, Leonardo suggested the use of rollers as well as lubricants between sliding surfaces. From this work, da Vinci fathered the concept of a “coefficient of friction.” Da Vinci used a value of 0.25 for the coefficient of friction between two “polished” surfaces, which is impressively close to estimates used today (500 years later). This feat is even more impressive due to the mathematical complexity of determining coefficients of friction between nonlubricated surfaces even today. Alongside friction, da Vinci was also interested in wear (a result of friction). In his day, mechanical objects experienced severe wear and either required frequent maintenance or replacement to maintain functionality. Da Vinci experimentally determined that the direction of wear depended on the load, and was not always vertically downwards, as was previously believed. His experiments also yielded that lubrication alone was insufficient to prevent wear. This led him to investigate the value of rolling elements. Source: Reti, Ladislao. “LEONARDO ON BEARINGS AND GEARS.” Scientific American, vol. 224, no. 2, 1971, pp. 100–11. Image: http://www.tribonet.org/wiki/friction-coefficients-in-atmosphere-and-vac... |

Katelyn Polson | ||

| circa. 1493 to circa. 1505 |

Compound Pulley System for Hoisting - Leonardo Da VinciCompound Pulley systems were of special interest to Leonardo Da Vinci. This was highlighted by the many sketches of Pulleys that was found in the Codex, and an example of a sketch is given in the picture. The sketch shows a simple pulley system hoist, which is a system that lifts or lowers a weight with the lesser amount of effort with an increase of pulleys present in the system. Moreover, he tried to associate various numbers to the various elements of the system to understand the concept of physics better. Sources:- LEONARDO3 - Leonardo da Vinci | MACHINES COLLECTON - COLLEZIONE DELLE MACCHINE, www.leonardo3.net/leonardo/semplici_eng.php. Image Courtesy:- Wikimedia Commons , private domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20Pulley-Da_Vinci.JPG |

Yamuna Ambalavanan | ||

| circa. 1493 to circa. 1497 |

Da Vinci's Scientific Approach to BearingsWork done by da Vinci both to understand friction and to design devices to overcome it were documented in his notebooks written between 1493 and 1497. He made observations on principles such as wear and coefficient of friction. These observations led him to understand the value of lubrication, cages, and the impossibility of perpetual motion. Most of what is known regarding da Vinci’s work on ball bearings comes from the Codex Madrid I. These works were found in 1967 and were written by da Vinci between 1493 and 1497. Previously, scholars had the Codex Atlanticus, which was a more random collection of writings and sketches created between 1483 and 1518. Material in the Codex Atlanticus is considered as drafts upon which da Vinci expanded and improved in Codex Madrid I. In these notebooks, da Vinci makes observations and predictions of system interactions that are not far off from the empirical values still used by tribologists today. The designs he proposes are novel and truly innovations that greatly influenced designs that are still considered the most efficient bearing designs today. Source: Reti, Ladislao. “LEONARDO ON BEARINGS AND GEARS.” Scientific American, vol. 224, no. 2, 1971, pp. 100–111., www.jstor.org/stable/24927729. Image: http://ebooks.library.cornell.edu/k/kmoddl/toc_leonardo1.html |

Katelyn Polson | ||

| circa. 1493 |

Friction and PulleyResearch in 2016, by scholar Professor Ian Sources: “Study reveals Leonardo da Vincis "irrelevant" scribbles mark the spot where he first recorded the laws of friction.” University of Cambridge, 21 July 2016, www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/study-reveals-leonardo-da-vincis-irrelevant-scribbles-mark-the-spot-where-he-first-recorded-the-laws. Image Courtesy: Codex Forster III folio 72r Credit: V&A Museum, London |

Yamuna Ambalavanan | ||

| circa. 1493 to circa. 1497 |

Balls, Rollers, and the Need for CagesIn addition to examining friction and wear that contacting elements experience, da Vinci explored the benefits that could be provided via the addition of rolling elements between the sliding plates. While it was known by ancient civilizations that rolling was more efficient than sliding, there is no evidence of the study of how and why this was true. Leonardo began his iterative design process with disk bearings. However, his studies showed that the wear experienced in the bearings would be more evenly distributed if balls/rollers were used in place of thin disks. One error da Vinci made in his work was failing to observe the differences between roller and ball bearings. In a quote from the Codex Madrid he remarked “I do not see any difference between balls or rollers save the fact that balls have universal motion whereas rollers can move only in one direction.” In fact, balls and rollers do behave differently depending on the type of loading applied (radial or axial). Regardless of that shortcoming, da Vinci was still very insightful in his observation of the need for individual bearing elements to be isolated. His work showed that if rolling elements contact each other during operation that the friction present between them is too great to gain a mechanical advantage. In contrast, if the elements are kept at a distance and only permitted to contact the two sliding surfaces via the implementation of cages, wear is greatly decreased and movement is much easier. Tribologists today are still impressed with the insights da Vinci provided in regards to rolling elements. Source: Reti, Ladislao. “LEONARDO ON BEARINGS AND GEARS.” Scientific American, vol. 224, no. 2, 1971, pp. 100–11. Image: Reti, Ladislao. “LEONARDO ON BEARINGS AND GEARS.” Scientific American, vol. 224, no. 2, 1971, pp. 100–11. |

Katelyn Polson | ||

| 1494 to 1559 |

The Italian WarsBeginning in 1494, King Charles VIII of France launched an invasion of the Italian peninsula. During this time, France had already begun the transition from a semifeudal state to a nationstate, shifting France away from the medieval period toward the renaissance. Upon crossing the Alps, the French army had a significant advantage over the Italians. Their cavalry and infantry were accompanied by small, light mobile artillery that would ensure their victory. The main strategy of the Italian people was to use their heavy walls and fortifications to withstand enemy invasion. However, because of the superior firepower and effective use of cannons by the French, they were able to conquer the Italian cities with ease. The French cannons were far superior to the cannons of the Italians, which were outdated and primitive. The light, cast bronze cannons could be shot quickly and easily, making them effective for destroying walls and terrorizing the Italian population. Because of new gunpowder-fueled siege weaponry, specifically culverins and bombards, the medieval strategy of building fortresses was proving to be obsolete. The significant advancements in cannons and firearms would force the world to redesign cities and defenses, drastically reinventing the way war is waged. The invasion by Charles VIII was only the first of many invasions of Italy through the 16th century. As the Italian Wars continued for another 60 years, Italy was constantly under threat from both foreign and domestic powers. This ongoing war led to an economic downturn that severely hindered new art or great works in Italy. Not even the church could afford to commission new art. By 1516, Leonardo Da Vinci had already left Italy to find a more welcoming artistic environment in France. By 1527, the Spanish had conquered Rome, costing Italy its "political and individual freedom" (Ewhelan). Ultimately, this would be the beginning of the end of the Italian Renaissance and the beginning of the Counter-Reformation. Sources: The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Italian Wars.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 4 Mar. 2016, www.britannica.com/event/Italian-Wars. “Italian Wars.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 21 Feb. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Italian_Wars. Ruggiero, Guido. The Renaissance in Italy: a social and cultural history of the Rinascimento. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015. The Italian Wars, 1494-1559, www.historyofwar.org/articles/wars_italian_wars.html. “What was the impact of Charles VIIIs invasion of Italy (1494) on the Renaissance?” - DailyHistory.Org, dailyhistory.org/What_was_the_impact_of_Charles_VIIIs_invasion_of_Italy_(1494)_on_the_Renaissance%3F. Ewhelan. “Why did the Italian Renaissance End?” Why did the Italian Renaissance End? - DailyHistory.Org, dailyhistory.org/Why_did_the_Italian_Renaissance_End%3F. |

Steven Mazzochi | ||

| circa. 1495 |

Leonardo's Mechanical KnightLeonardos mechanical knight consisted of a suit of armor with a set of gears and pulleys inside designed to mimic human motion. Like his lion, the original knight has not survived, but a modern reconstruction has been made by Mark Rosheim. DaVinci's knight wasused for enternainment for Lodovico Sforza and his guests. The knight likely would have been powered by springs or a waterwheel, and could have sat, stood, raised its visor, and moved its arms. Image source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonardo%27s_robot Erik Moller. Leonardo da Vinci. Mensch - Erfinder - Genie exhibit, Berlin 2005 Information Source: https://www.leonardodavinci.net/robotic-knight.jsp No Author. "Robotic Knight - by Leonardo da Vinci." Leonardo da Vinci. Retrieved 8 March 2018 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leonardo%27s_robot No Author. "Leonardo's robot". Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 March 2018 |

Joshua Walker | ||

| 1496 to 1499 |

St. Mark's ClocktowerSt. Mark’s Clocktower, located on the Piazza San Marco in Venice, Italy, is an architectural representation of an analog and digital clock with the added embellishments of a Madonna and child, a winged lion, the symbol of Venice, and a bell which two bronze statues (the Moors) ring. The Madonna and Child are made of bronze, and they rest above the analog clock, seemingly looking down over time and space. Space is included in this clock because of the use of the zodiac signs on the clock face, as well as the representation of the Ptolemaic universe in which the sun rotates around the Earth (though the Earth has since been removed from the clock as the Copernican theory of space has become accepted). The Madonna and Child harken back to the Byzantine ideals of anagogic space, and twice a year, at Epiphany and on Ascension Day, the three Magi appear from a doorway which is usually covered by panels displaying a digital clock face. These three Magi, led by an angel, proceed across the clock face and bow to the Madonna and Child. This procession was broken for a long period of time following construction, but in a series of repairs led by Bartolomeo Ferracina from 1757 to 1759, their sequence was fixed. On top of this, the digital clock from which these three magi emerge was also a part of a restoration and enhancement project. In an effort led by Luigi de Lucia from 1858-1866, panels were made in the doorways next to the Madonna and Child which displayed the hour on the left and the minutes on the right, changing every five minutes. One interesting detail about the placement of the Madonna and Child as opposed to the winged lion, is that the lion is raised higher than the other figures, thus implying a sort of superiority of state over religious symbology. Sources used: Muraro, Michelangelo. “The Moors of the Clock Tower of Venice and Their Sculptor.” The Art Bulletin 66.4 (2014): 603-609. College Art Association. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. “St. Mark’s Clocktower.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 25 Jan. 2018. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.

Image provided courtesy of http://www.planetware.com/venice/st-marks-square-i-vn-vpsm.htm |

Alicia Geoffray | ||

| 1497 |

Design for a Lock at San MarcoOne of Da Vinci's most enduring creations was the miter lock. It was immediately put into use in Milan, then spread across the world, and is now used today in almost any waterway. Previous lock designs would take one or two men to move the locks up against the force of gravity. This design utilizes horizontal movements to open and close the lock. The miter lock is the joining of two walls at a 45 degree angle. This allows them to push against each other when faced with the force of oncoming water, making their bond tighter. This invention is just one of the many examples of how Leonardo Da Vinci was a revolutionary engineer of his time. The design was completed in MIlan in 1497. Sources: “The Canal Lock.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Inventions, www.leonardodavincisinventions.com/civil-engineering-inventions/leonardo.... “Leonardo's Miter Gate.” Linda Hall Library, civil.lindahall.org/mitergate.shtml. Image Source: Linda Hall Library, https://civil.lindahall.org/mitergate.shtml |

Laila Kassar | ||

| circa. 1497 |

Designs Enabled by Ball BearingsDa Vinci’s work on ball and roller bearings was hugely useful in helping him to design other larger inventions. With his knowledge of the advantages of bearing use and design of to improve their implementation he was able to create many other novel inventions which would not have been possible if only sliding contacts were used. For example, both da Vinci’s self-propelled cart as well as his armored car (tank) would not have been possible without bearings. In his armored car, there were a number of cannons mounted to a circular platform that could rotate 360 degrees. The rotation of a large and heavy platform could only be made possible via the use of rolling element bearings. Similarly, his sketches of a self-propelled cart relied heavily on bearings. In 2006 when scholars built a model of the cart based on his sketches, it was able to work. Again, this was enabled by ball bearings. Many others of Leonardo da Vinci’s inventions made use of bearings as well. Almost every design that included two contacting elements moving relative to each other was improved and made more possible thanks to improvements in bearing design via race ways and cages as well as lubrication. Designs such as da Vinci’s flying machine, while not feasible due to weight to lift ratio limitations, was still improved via the incorporation of bearings. His robotic knight, like many modern robots, contained several moving parts who’s motion was made easier and less resource intensive due to bearings. Today the uses of bearings are limitless. They can be found in simple toys such as fidget spinners as well as complex, high speed manufacturing lines and autonomous robots. Sources: The Inventions of Leonardo Da Vinci. http://www.da-vinci-inventions.com/. Accessed 1 Mar. 2018.

Leonardesque Models at the Museum - Museoscienza. http://www.museoscienza.org/english/leonardo/models-exhibited/. Accessed 1 Mar. 2018.

Image: http://www.leonardodavincisinventions.com/war-machines/leonardo-da-vinci... |

Katelyn Polson | ||

| circa. 1500 |

Da Vinci's Mortar and Machine GunWhile Leonardo Da Vinci did not invent the mortar, it was an extremely significant piece of weaponry. Early mortars were used to lob exploding projectiles over fortress walls or into enemy cities. One of Da Vinci's sketches depicts using mortars with fragmenting and exploding fire bombs. This type of projectile not be used until the late 1600s, many years after Da Vinci imagined them. These mortars also implement the elevation mechanism present in his cannon designs. A second revolutionary design by Da Vinci was the "machine gun", his vision of a superior cannon. His sketches show a specialized aiming mechanism with a fan-shaped spread of small barrels capable of firing in multiple directions at once. Another sketch consists of 33 short barreled guns in rows of 11 mounted to a cart. Unlike traditional cannons, these smaller barrels resemble traditional guns, however they are mounted to a frame that should be lightweight and more maneuvarable than cannons. Da Vinci realized the importance of speed and agility in warfare, inspiring him to design relatively slim and nimble weapons that could be loaded and fired quickly. World History Project says this about Da Vinci's machine guns, “[Leonardo] wanted to increase the rate of firing weapons and so designed machines with multiple cannons, so they could be fired successively or all together. Many people consider these the forerunner of the modern machine gun. Two of these used racks of eleven or fourteen guns. While the top row was being fired the next rack was loaded; at the same time, a third rack was cooling off. Another design had the guns in a triangle spread for greater distribution of the projectiles." Da Vinci was correct in his designs, as mortars and cannons would be the driving force behind invasions for centuries to come. Sources: “Mortar (Weapon).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 17 Feb. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mortar_(weapon). Image Source:https://www.1000museums.com/art_works/leonardo-da-vinci-sketch-of-a-mort... “Machine Gun.” Machine Gun by Leonardo da Vinci, www.leonardo-da-vinci.net/machine-gun/. “Leonardo da Vinci Sketches the Design for a Machine Gun.” World History Project, worldhistoryproject.org/1500/leonardo-da-vinci-sketches-the-design-for-a-machine-gun. |

Steven Mazzochi | ||

| circa. 1500 |

ClockLeonardo da Vinci wrote about a clock design that was more accurate than the clocks of his time in his book, Codex Atlanticus. He did not invent the clock, but he did make improvements to the current design. Da Vinci’s clock had two separate mechanisms for both minutes and hours, comprised of weights, gears, and harnesses. There was also a dial that kept track of changing moon phases, and he incorporated diamonds and rocks in the design. The biggest change from the conventional clock of the time was that da Vinci utilized springs instead of weights to operate his clock. However, his design was never brought to fruition. By the 17th century, pendulums were incorporated into clock design and brought new innovation to traditional clock design.

Sources: “Clock.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Clock Invention, 2008, http://www.da-vinci-inventions.com/clock.aspx. “Clock.” LEONARDO DA VINCI'S INVENTIONS AND IDEAS, www.leonardo-davinci-inventions.weebly.com/clock.html. Image Source : Leonardo da Vinci (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_da_Vinci_dial_of_Venus.jpg), "Leonardo da Vinci dial of Venus", marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Template:PD-old. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| circa. 1500 |

Scuba GearEver the military engineer, da Vinci generated designs for scuba gear that would allow for sneak attacks underwater during his time spent devising plans to defend the city of Venice. He believed soldiers with special equipment for diving (see picture) and with a breathing apparatus could be an effective method to sabotage enemy ships. The original concept for scuba gear was comprised of a leather suit and a mask with tubes attached to a cork floating on the surface of the water. However, this idea never really reached fruition, and is an example of one of da Vinci’s inventions that appeared too far-fetched for the people of the time to entertain. Luckily for Venice, they were able to thwart enemy forces before a need for such underwater warfare would have been necessary. The ingenuity of his scuba suit and original air bladder to aid with breathing was eventually explored by Jacques Cousteau who constructed the first aqua-lung model with Émile Gagnan that aided in the beginnings of deep sea exploration.

Sources: “Scuba Gear.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Scuba Gear Invention, 2008, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/scuba-gear.aspx. Campbell, Shawn. “Da Vinci's Scuba Gear.” Leonardo Da Vinci's Life, www.davincilife.com/scuba-gear.html. Image Source : Permission granted by The British Library (https://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/leonardo/diving.html) for use under the public domain and is attributed to the model-maker Simon Sanderson, from a design by Scott Cassell. |

Chiranth Kishore | ||

| circa. 1500 to circa. 1510 |

Clock MainspringIn the first decade of the 16th century, a German locksmith from Nuremberg named Peter Henlein began using springs to power clock mechanisms. Winding the “mainspring” stored energy, which was slowly released over time, turning the hand of the timepiece. Because spring could be made much smaller and stiffer than a traditional verge escapement mechanism, the weight and size of Henlein’s timepieces were significantly reduced. This breakthrough led the clock from being a tower-sized mechanism in the center of town to a small pocket- or wall-sized device that wealthy gentlemen could carry around with them throughout the day. However, these early mainspring watches still had their faults. Naturally, the clock would run faster initially, when the spring was tightly wound, and slow down as the spring became loose. Later, a solution to this problem, the “fusee” was developed to release the tension of the spring over time more evenly. The ability of an individual to have access to a relatively accurate timepiece anywhere they went had a significant impact on the daily lives of people in 16th century Europe, allowing activities throughout the day to be recorded with more precision than ever before. Sources: “Spring Driven Clocks.” 2018. https://www.merritts.com/merritts/library/spring_driven_clocks.aspx. Accessed 8 Mar 2018. Bellis, Mary. “Spring-Powered Clocks.” The History of Mechanical Pendulum Clocks and Quartz Clocks. 7 April 2017. https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-mechanical-pendulum-clocks-4078405. Accessed 8 Mar 2018. Image: Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alarm_clock_mainspring.JPG. |

Derek Jones | ||

| circa. 1503 |

The Mona LisaThe Mona Lisa, arguably the most famous painting in the world, is an oil painting created by Leonardo Da Vinci sometime between 1503 and 1519 during the time he lived in Florence. It now hangs in the Louvre in Paris, France. Da Vinci's style was revolutionary, and set the standard for all future portraits. The painting is a masterpiece of Da Vinci's techniques, and is a unique synthesis of the subject and the landscape behind her. Her hair and clothing are given a soft look by use of fine shading, or sfumato. The background is a vast landscape that goes on seemingly endlessly, which is juxtaposed with the very close, touchable subject of the painting. Its detail shows Da Vinci’s focus on new levels of natural representation of the subject and influenced many artists to come. Leonardo Da Vinci was also known to be fascinated by the ideas of geometric perfection, and whether deliberate or not, the painting exhibits the properties of the golden ratio and the Fibonacci spiral.

Sources: “Mona Lisa.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 18 Aug. 2017, www.britannica.com/topic/Mona-Lisa-painting. “Leonardo da Vincis Mona Lisa.” ItalianRenaissance.org, 30 Sept. 2015, www.italianrenaissance.org/a-closer-look-leonardo-da-vincis-mona-lisa/.I... Source: Encyclopædia Britannica, www.britannica.com/topic/Mona-Lisa-painting.

|

Laila Kassar | ||

| circa. 1504 |

Arno River ProjectDa Vinci’s watermill wasn’t his only attempt to control the flow of water. One of his most ambitious projects was an attempt to construct a channel and a dam to divert the river Arno away from Pisa so that the city could no longer cut off Florentine trade. The plan was made in conjunction with another historically significant Florentine, Niccolo Machiavelli. Da Vinci for the project, designed not only the dam and channel, but also many machines intended to assist in construction. Unfortunately, as was so often the case of Leonardo, he was ahead of his time, and Florence simply did not have the resources to conduct a project on this scale. While theoretically feasible, it wasn’t economically feasible. While the project never came into fruition, the notion of controlling the flow of a river would live on past Leonardo, and would, eventually, succeed. https://leonardodavinci.stanford.edu/submissions/dgill/FinalProject/Leon... Image from Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain |

Ian Campbell | ||

| circa. 1505 |

Renaissance Painting TechniquesThe Renaissance brought about a new tradition in the field of art. Artists sought to achieve a greater sense of realism and naturalism in their paintings, as opposed to the rigid and stylized characteristics of the preceding medieval and byzantine periods. Artists were aided in achieving this goal in part through the development of oil paint, which in turn gave rise to the development of new painting techniques. The most important techniques that were established during the renaissance were sfumato, chiaroscuro, perspective, foreshortening and proportion. The advent of these techniques marked a significant shift in art history. Sfumato, a term coined by Leonardo da Vinci, refers to the subtle blending of colors and the blurring of sharp lines. Chiaroscuro is the use of strong contrast between light and dark to create depth. Perspective, foreshortening and proportion all relate to the use of mathematical principles to establish lines used to create the illusion of depth. Used in combination, these techniques greatly contributed to an artist’s ability to create three dimensional figures on a two-dimensional plane.

Sources Gombrich, E. H. Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. Princeton University Press, 1960. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. “Renaissance Art.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. , 6 Mar. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_art#Techniques. Image Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons, fair use

|

Lauren Krieger | ||

| circa. 1505 |

Raphael’s Small Cowper MadonnaRaphael’s Small Cowper Madonna is a rendition of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child which is located in Washington D.C. in the National Gallery of Art. This painting is an oil on panel, and it depicts Mary and Child in an Italian countryside with a church in the background on the right-hand side. Mary, represented as blonde and with fair skin, sits in the front center of the piece wearing a vibrant red dress. There appears to be an exceedingly faint, almost translucent golden halo behind her head. This halo harkens back to the Byzantine technique invoking a sort of anagogic space; however, Raphael invokes this sense of otherworldliness without the typical stiffness and two-dimensionality often found in Byzantine art. Mary holds the baby Christ in her lap, and emotion can be seen in his expression as he glances over her shoulder. This movement and emotion within the piece is another sharp deviance from the previous paradigm of Byzantine art which focused more on religious symbology than on realism of the material world.

Sources Used: Brown, David Alan. "Raphael's 'Small Cowper Madonna' and 'Madonna of the Meadow': Their Technique and Leonardo Sources." Artibus Et Historiae 4.8 (1983): 9–26. JSTOR. Web. 28 Feb. 2018. “Small Cowper Madonna.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 18 Feb. 2018. Web. 28 Feb. 2018.

Image Courtesy of Wikipedia, page titled Small Cowper Madonna. Image is Public Domain. |

Alicia Geoffray | ||

| 1508 to 1511 |

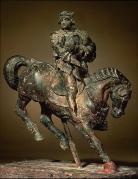

Horse and RiderA 24-foot horse sculpture was commissioned by the Duke of Milan to be built, and Da Vinci did not back out of this challenge. If built it would have been the largest sculpture of a horse in that period. To do so, Da Vinci created a miniature beeswax model to emulate the 24-foot model. He even conquered design challenges like mold making and heating a large amount of bronze for the sculpture through his notes. However, the amount of bronze required was bartered for the prevention of invasion by the French. Thus he did not practice the various design methods he conceptualized. However, the sculpture is now renown to be unlike any other work of his, especially because of the contrast of his earlier works as an apprentice. Moreover, there is an impression of a thumb on the rider’s chest that is said to be Leonardo’s. Sources:- “Colossus.” Leonardo da Vinci's Colossus Invention, www.da-vinci-inventions.com/colossus.aspx. “Horse and Rider (Leonardo da Vinci).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Mar. 2018, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horse_and_Rider_(Leonardo_da_Vinci). Image Courtesy:- Wikimedia Commons , public domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Leonardo_Da_Vinci_Horse_and_Ride... |

Yamuna Ambalavanan | ||

| circa. 1510 |

The da Vinci GlowLeonardo da Vinci was known for many things; art, architecture, weapons, and anatomy. He is rarely thought of for his work in astronomy. He had a great interest in the moon and its relationship to the Earth and the sun. One of his most interesting achievements in the field of astronomy was his understanding of earthshine. After sunset on a night with a crescent moon, an ashen glow appears on the surface of the moon, the section of the moon which is in Earth’s shadow lights up faintly, and for thousands of years no one could explain how part of the moon was still slightly illuminated when there was no apparent light source acting on it. Leonardo was intrigued by the phenomenon and set out to discover the answer behind the mystery. He spent many hours studying and observing the moon, and then he finally had a breakthrough. It was because of the Earth! He came to the conclusion that the light coming from the sun would reflect onto the oceans of the earth, and in turn create an ashen glow on the moon itself. Leonardo had previously determined that the moon had an atmosphere and bodies of water on it, this would make the moon a great reflector of light, meaning that even a small amount of light creates some kind of reflection of light off of the darkest part of the moon. Source: "The Da Vinci Glow." NASA. 4 Oct. 2005. https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2005/04oct_leonardo. Accessed 27 Feb. 2018. Image source: NASA. Public Domain. https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2005/04oct_leonardo. |

Rachel Lee | ||

| 1511 |

Death of Marcantonio della TorreLeonardo da Vinci originally planned to publish his anatomical notes in the form of a book. In this endeavor he had the support of Marcantonio della Torre, a professor at the University of Padua who shared da Vinci's interest in dissections and human biology. However, Marcantonio's life was cut unexpectedly short by the plague, an event that severely curtailed da Vinci's attempts to publish his notes. Coupled with political turmoil in Italy that following year, it spurred da Vinci's relocation to France, and the eventual ending of any of his attempts to bring his anatomy work to the general public. Source: Image source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marc_Antonio_della_Torre_(Turrianus)._Line_engraving,_1688._Wellcome_V0005857.jpg |

Shelly Tan | ||

| 1511 |

Anatomical Manuscript B, Leonardo da Vinci

Anatomical Manuscript B is Leonardo da Vinci’s most comprehensive sketchbook and physical description of the human body. In 1508, he began the manuscript during a dissection of a recently deceased old man who passed in a Florence Hospital. Leonardo stated in the manuscript that, “this old man, a few hours before his death, told me… that he felt nothing wrong with his body other than weakness… and I dissected him to see the cause of so sweet a death.” He attributed the man’s death to lack of blood flow to the heart and a damaged liver. Leonardo continued the manuscript with a dissection of over 30 other cadavers; and with the help of Marcantonio della Torre at the University of Padua, completed it around 1511. Anatomical Manuscript B contains carefully sketched depictions of various organs, muscle groups, skeleton, and much more with highlights including a drawing a developed fetus and astoundingly accurate spinal cord. Sources: Royal Collection Trust. “The Centenarian: Anatomical Manuscript B”. Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist: The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace. The Royal Collection Trust, 2018. Web. 15 Feb. 2018. Link

Sooke, Alastair. “Leonardo da Vinci’s groundbreaking anatomical sketches”. Art History. British Broadcasting Company, 21 Oct. 2014. Web. 15 Feb, 2018. Link Image Source: Image courtesy of The Medievalist.net in article "Exhibition reveals the genius of Leonardo's anatomical work". Link |

Thomas Knowles | ||

| 19 Dec 1513 |

Apostolici Regiminis, Pope Leo X

Apostolici Regiminis was a papal bull declared by Pope Leo X in a doctrine concerning the nature of the human soul. An aspect of the Bull required all “natural philosophers,” scientific researchers of the time, to solely conduct work in support of church doctrine, in particular its stance on the origin of the soul. Apostolici Regiminis refined the church’s view of the soul as “really, of itself, and essentially, the form of the body,” further explaining that each body contains a soul of its own. This restricted anatomical researchers, Leonardo da Vinci for example, to aim their dissections in search for the connection between the spiritual soul and physical body. Dissection for any other reason was blasphemy. For this reason, those curious to dissect cadavers often took residence in Rome to study under the Papacy and reduce potential accusations of sacrilege. In late 1513, Leonardo da Vinci left Milan for Rome, where we continued to study anatomy until Giovanni degli Specchi accused him of Necromancy, ending his experiments. Sources: Catholic Online. “Apostolici Regiminis”. Catholic Encyclopedia. Catholic Online, 2018. Web, 15 Feb. 2018. Link

Gilson, Hilary. “Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519)”. The Embryo Project. Arizona State University, 26 Aug., 2008. Web. 15 Feb. 2018. Link Image courtesy of Wikipedia, page Pope Leo X, titled Raphael's Portrait of Leo X with cardinals. Image is Public domain |

Thomas Knowles | ||

| circa. 1514 |

The Copernican ModelNicolaus Copernicus was born on Feb. 19, 1473 in Poland. At the age of 10, his father died, leaving him to be cared for by his uncle who oversaw his education. At the age of 18, he traveled to Italy to attend college where he intended to study the laws and regulations of the catholic church and become a canon. He instead spent a majority of his time studying mathematics and astronomy. While away at school, his uncle was elevated in his church to the position of Prince-Bishop of Warmia which gave him the opportunity to place Nicolaus in the Warmia canonry. After 7 years, he earned a doctorate in canonry and law, but remained more interested in astronomy. During his time at the University of Bologna, he lived and worked under astronomy professor Domenico Maria de Novara. When he returned home and was able to live in a tower which had an observatory that he looked through in his spare time. During many hours observing the night sky, he began to question the theory that had been proposed by Aristotle and Ptolemy 1400 years earlier. This theory was that of the Ptolemaic system, in other words, a geocentric universe. He first noticed some striking problems with the mathematics of the system, the paths of the celestial bodies were too complex and sometimes the planets would travel backwards. Astronomers call this “retrograde motion” and Ptolemy accounted for this by incorporating circles inside other circles, known as eclipses. Unfortunately these paths were too complicated to have occured naturally, so Copernicus eventually doubted the system as a whole. He finally determined that the earth’s motion in space creates the retrograde motion of the other planets, the rotation of the earth on its own axis is what causes the rising and setting of the sun, and most importantly, the Sun is the center of the universe, not the Earth. With this conclusion he was able to simplify the paths of the planets and stars, determine the order of the planets, and create his own system, the Copernican system. Sources: Redd, Taylor. "Nicolaus Copernicus Biography: Facts and Discoveries." Space.com. 19 Feb. 2013. https://www.space.com/15684-nicolaus-copernicus.html. 28 Feb. 2018. Image source: Space.com. Public domain. https://www.space.com/15684-nicolaus-copernicus.html. |

Rachel Lee | ||

| The middle of the month Summer 1515 |

Mechanical LionLeonardo made an autonomous mechanical lion which opened to reveal lillies and other flowers, symbolizing the bond between 2 powerful families of Florence and France, with the lion representing Florence and the flowers France. The original mechanical lion has been lost, but a replica hhas een made at the Chateau du Clos Luce and Parc. The original lion could supposedly walk, move its head, and reveal the flowers hidden inside its body. Image Source: https://dangerousminds.net/comments/leonardo_da_vincis_incredible_mechan... Gallagher, Paul. "Leonardo Da Vinci's Incredible Mechanical Lion and History's first Programmable Computer". DangerousMinds.net, 14 September 2013. https://dangerousminds.net/comments/leonardo_da_vincis_incredible_mechan.... Accessed 8 March 2018 All images posted on Pinterest are |

Joshua Walker | ||

| circa. 1516 |

De Humanis CorporeDe humanis Corpore is an unpublished textbook Leonardo Da Vinci was working on for a large portion of his life. The textbook was planned to have been finished in 1516 CE but Leonardo Da Vinci never finished the book. It was planned to have 120 sections with extensive amounts of illustrations. The textbook was meant to explain each of the organs and apparatus’ of anatomy, physiology, and pathology in the human body. A section of the book was also going to be dedicated to a comparative discussion of human and animal anatomy. The textbook was largely finished and it is known that Leonardo employed two collaborators to organize the drawings (268 pages of anatomical drawings) and annotations he had wrote. It is theorized that Leonardo chose not to publish and finish his textbook due to being afraid of the textbook being too controversial for this time period. This theory was proposed because in his drawing of the heart and blood circulation Leonardo wrote “I could tell more, if I was allowed to do so.”

Source: Sterpetti, Antonio V. The Revolutionary studies by Leonardo on blood circulation were too advanced for his time to be published. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2015, vol 62 (1): 259-263. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2015.10.001 Image Source: Sterpetti, Antonio V. Anatomy and physiology by Leonardo: The hidden revolution?. Surgery 2016. Vol 159 (3): 675-687. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2015.10.001. |

Amanda Gozner | ||

| circa. 1517 |

Romorantin PalaceFrom 1517 until his death in 1519, Leonardo Da Vinci lived in Amboise, France as a guest of King Francis I. Sketches for a royal palace in Romorantin are found in Da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus. In these sketches, he outlines a plan for a new town at Romorantin. The overall concept of Da Vinci’s design was centered around incorporating the existing royal buildings in the town into a new network of gardens and chateaus. His plan included a canal system to adequately drain the area and prevent flooding that plagued the area due to the Saudre River. King Francis I financed this portion of the project in 1518, but he ultimately decided not to pursue the construction of the Romorantin. He decided to build a chateau in Chambord instead, so Da Vinci’s designs for the Romorantin Palace were never constructed. Sources: Pedretti, Carlo. “Leonardo Da Vinci: The Royal Palace at ...” Abebooks.com, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1 Jan. 1972, www.abebooks.com/Leonardo-Vinci-Royal-Palace-Romorantin-Pedretti/9101029.... Tanaka, Hidemichi. “Leonardo Da Vinci, Architect of Chambord?” IRSA, vol. 13, no. 25, 1992, www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1483458.pdf?acceptTC=true&coverpage=false. |

Scott Lenz |