Timeline: Race, Gender, Class, Sex

Created by Dino Franco Felluga on Thu, 08/06/2020 - 19:07

Part of Group:

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research some aspect of the nineteenth century that teaches us something about race, class, or gender and sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class or gender/sex in the 19th century to our collective resources in COVE. Provide sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural detail that you are presenting. Try to interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research some aspect of the nineteenth century that teaches us something about race, class, or gender and sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class or gender/sex in the 19th century to our collective resources in COVE. Provide sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural detail that you are presenting. Try to interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

Timeline

Chronological table

|

Date |

Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The middle of the month Summer 2001 |

The Murder of Sereena AbotswaySereena Abotsway was 29 years old when she disappeared in August of 2001. She was reported missing by her foster mother on August 22, 2001. Sereena’s murderer, Robert Pickton, was caught much later. Abotsway was one of six women “whom Port Coquitlam pig farmer Robert Pickton” has been accused of killing. Pickton was a serial killer who usually targetted sex workers, and many of the sex workers in Pickton’s nearby community in Vancouver were Indigenous. This demonstrates a larger social issue of Indigenous people having fewer socioeconomic opportunities than their other racial counterparts, therefore turning to work such as sex work. Sex work has connotations of dirtiness, shame, and unethicalness; meaning that when issues occur to those who do sex work, people tend to be less sympathetic. The facts of her work and drug addiction illustrated the media’s tendency to show Indigenous peoples in a negative light. Abotsway’s work and life choices were used to help dehumanize her and feed social stereotypes about Indigenous women despite her being a victim. This can also be seen in news headlines regarding her murder, such as the article in the Vancouver Sun titled “Sereena Abotsway: A troubled child who once won a trip to Holland eventually wound up on the streets of Vancouver.” Headlines such as this one makes the victim sound like the problem and the issues they face as due to their own life choices, while the positive aspects of their life were due to outside factors. Additionally, “Some friends and relatives of the victims complain that police didn’t respond quickly enough to missing person reports because most of the women supported their drug habits with prostitution. And now the families hope positive memories about the women can rise above the troubling evidence that is expected to emerge from Pickton’s first trial.” Sereena’s brother wrote that “Sereena did not choose to live life the way she did, circumstances chose it for her.” He continues later by stating that “Sereena quite often, when talking to us on the phone, would ask us to make sure that the younger [foster] children would never end up living the life that she was living.” Furthermore, Abotsway’s missing and murdered case took place in 2001, a year before the Native Women’s Association, Amnesty International Canada, KAIROS, Elizabeth Fry Society, the United Church, and the Anglican Church came together to form the “National Coalition for our Stolen Sisters.” Since this historical movement first formed, cases of discrimination against Indigenous women countinue to be incredibly high even among other women in racial minoirities.

Sources: Culbert, Lori. “Sereena Abotsway: A Troubled Child Who Once Won a Trip to Holland Eventually Wound up on the Streets of Vancouver.” Vancouver Sun, Vancouver Sun, 19 May 2017, vancouversun.com/news/local-news/sereena-abotsway-a-troubled-child-who-once-won-a-trip-to-holland-eventually-wound-up-on-the-streets-of-vancouver. Miller-Tanner, Makoons. “Sereena Abotsway, Murdered by Serial Killer in British Columbia in 2001.” Justice for Native Women, Dec. 2018, www.justicefornativewomen.com/2018/12/sereena-abotsway-murdered-by-seria.... “Timeline.” KAIROS Canada, 2020, www.kairoscanada.org/missing-murdered-indigenous-women-girls/inquiry-tim.... |

Crystal Webb | ||

| 1981 to 14 Spring 1999 |

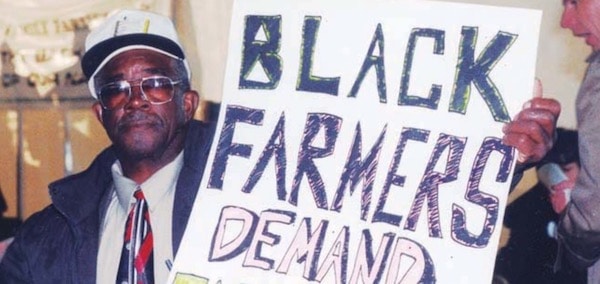

Pigford vs Glickman TimelineThe Pigford vs Glickman case was a lawsuit against the USDA because of their racial discrimination against African-American farmers. These allocations all started coming about from the period 1981 through 1996. During the Great Depression, there was a White dominance in the Democratic party in the south that overlooked the African-American farmers. By the year 1992, the number of black farmers had decreased by almost 98%. As early as 1981 allocations began to arise that the USDA was not fairly treating African-American farmers with the same respect that they did as other groups. These farmers were saying that they were being denied loans or that they were told that they would have to wait longer to receive the approval for the loans. Many of these farmers were facing foreclosure and financial ruin because of the USDA denying these loans. In 1994 the USDA commissioned a study on the treatment of minorities in the FSA or also known as the Farm Service Agency. The study specifically examined crop payments and disaster payment programs. From the years 1990 to 1995 it was shown through the research that the minorities had received much less help from the FSA. In 1996, the Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman ordered that government foreclosures be suspended so that the issue of discrimination could be investigated. During this time protests began to rise. They were protesting against the USDA. They were saying the USDA should have been there for them and their employees. They felt that the USDA was a "Crude Joke" because it had not helped them at all in any way shape or form. In 1997, the trial of Pigford vs. Glickman began and it was a lawsuit on the USDA for the withholding of loans to minority groups such as African-Americans. On April 14, 1999, the lawsuit was settled. This settlement now makes sure that the USDA has to meet certain guidelines when making loan decisions for these farmers.

Sources: Cowan, Tadlock and Feder, Joey."The Pigford Cases: USDA Settlement of Discrimination Suits by Black Farmers. PDF" Congressional Research Service, 29 May 2013. https://nationalaglawcenter.org

|

Charles Brunswick | ||

| 1972 to 1980 |

ACLU womens rights projectIn 1972, Ruth Bader Ginsburg co-founded the Womens Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). She did this until she got appointed to the federal bench in 1980. While Ruth was apart of the ACLU, she led some of the most important legal cases to the supreme court. Many of these cases established a foundation for current legal matters against sex discrimination in America and helped create a foundation for womens rights in the future. by 1974, ACLU participated in over 300 sex discrimination cases and through 1969-1980, 66 percent of gender discrimination cases were decided by the supreme court. Ruth wanted to ensure that the ALCU was spreading awareness and making a difference in womens rights and equality. She stated, "I want to be a part of a general human rights agenda... [promoting] the equailty of all people and the ability to be free". “ACLU History: A Driving Force for Change: The ACLU Women's Rights Project.” American Civil Liberties Union, 1 Sept. 2010, www.aclu.org/other/aclu-history-driving-force-change-aclu-womens-rights-.... |

Riana Doretti | ||

| 1909 |

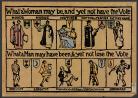

Clemence and Laurence Housman found the Suffrage Atelier "What a woman may be, and yet not have the vote". This banner was produced at the Suffrage Atelier in 1912. Wikimedia Commons. Following the formation of the Artists' Suffrage League, founded by renowned stained glass artist, Mary Lowndes, in 1907, which produced illustrated banners, postcards, and pamphlets used to promote the campaign for women's enfranchisement in Britain and North America, Clemence and Laurence Housman established their own Suffrage Atelier in 1909. Its practices took place at artists' homes, before the Housman siblings offered the site of their small home, Pembroke Cottage in Kensington, as its headquarters. Though the location of its headquarters would change three more times within its five operational years, the collective vision of the Atelier remained the same: it was to act as an arts and crafts society which worked towards the enfranchisement of women, with an additional effort to encourage artists to forward the women's movement by means of pictorial publications. (VADS, "The Women's Library: Suffrage Banners") In contrast with its predecessor, the Artists' Suffrage League, the Housmans' Suffrage Atelier encouraged non-professional visual artists and enthusiasts to submit their work to the cause in addition to professional artists, and also offered a small percentage of the sold works' profits as compensation. The Atelier also contrasted with its associates, the Women's Freedom League (1907-61) and the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) (1903-17), stylistically, by means of the colours its members chose to use in the creation of its feminist propaganda. While the other organizations used white, green, and purple, which are commonly known as the defining colours of the suffrage movement, the Atelier used a broader range of hues, as depicted in one of its banners (at left), wherein blue, black, and gold are used. Clemence led the team, and also lent her talents as an embroiderer, illustrator, and wood engraver to the Atelier, often spending entire days sitting on a floor cushion, doing her needlework or engraving in order to benefit the cause. Laurence designed a number of the Atelier's banners. As Clemence Housman was a respected member of the WSPU, much of the Atelier's work could be found for purchase within its store chains and also within the pages of its national newspaper. The Atelier held printmaking workshops and competitions in addition to the numerous exhibitions, political rallies and processions its members would regularly attend and circulate their artwork at, while also allowing for new and meaningful relationships to be forged between women as they worked collaboratively to aid a feminist cause which married the artistic with the political. The feminist nature of the workshop's artistic operations also subverted the common belief that embroidery and needlework reinforced women's domestic place within the home. The Suffrage Atelier ran from 1909-14. (Morton, "Changing Spaces: Art, Politics, and Identity in the Home Studios of the Suffrage Atelier") |

Alex Heath | ||

| 4 Apr 1906 |

Aborigines Act 1905

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| The start of the month Autumn 1903 to 1917 |

WSPU FoundedOn october 10th, 1903, the WSPU was founded by Emmeline Pankhurst. The foundation was a militant wing of the womens suffrage movement in Great Britain. The group garnerd a lot of distaste in the time period because of their extreme methods. They would often interupt political meetings, hold huge marches, chain themselves to railings outside of parliment, and battled with the police. Some of their more problematic behavoirs included pouring acid on mailboxes and defacing artwork in the national gallery. When arrested, the women would often hold hunger strikes to garner media attention for their cause. However, once world war 1 arrived, these women slowly faded out to get behind the war efforts, and eventually the group officially disbanded in 1917. In 1918, the British government granted suffrage to women over 30 because of their efforts during the war. |

Samantha Johnson | ||

| Jun 1901 |

Hobhouse report on Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 30 Nov 1900 |

Death of Wilde

ArticlesEllen Crowell, “Oscar Wilde’s Tomb: Silence and the Aesthetics of Queer Memorial” Related ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 17 May 1900 |

Siege of Mafeking lifted

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Oct 1899 to 31 May 1902 |

Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Autumn 1899 to 7 Sep 1901 |

Boxer Rebellion (義和團運動)By the mid-19th century, Christianity spread and blossomed in China. Churches and Missionaries were all over the country, and this expansion casued conflicts with the local people. On a microscopic scale, this was seen by the Chinese as a bunch of Westerners spreading their Western degeneracy and eroding Chinese Culture. At the height of the hysteria, rumours were spread where these Westerners were scooping out children's eyeballs and collecting their semen for medicine. (The original term is "陽精" which means "male vitality") Despite the missionaries' attempts to build hospitals and schools for the locals, they are often ignored by the Chinese Locals. In 1868, a plague broke out in a French Monastery that led to the deaths of many babies. This event was seen by the locals as the French Missionaries killing said babies, which led to the public stoning of a French Minister. On a macroscopic scale, the Qing Dynasty was consistently losing their influence to neighbouring countries due to corruption and a failure to anticipate other countries. These repeated losses include: The Treaty of Nanking (南京條約) (1842), which gave Hong Kong Island to the British after the First Opium War; The Convention of Peking (北京條約) (1860), which gave the Kowloon Peninsula to the British and Outer Manchuria to the Russians after the Second Opium War; the Treaty of Aigun (璦琿條約) (1858), which ceded northern Manchuria to Russia; The Treaty of Tientsin (天津條約) (1858), which opened Chinese Ports to foreign trade and increased missionary activities to foreign countries; The Treaty of Bakan (馬關條約) (1895), which gave Taiwan to Japan. These are just part of the countless treaties where China was unable to defend itself towards foreign powers, but it is generally agreed by historians that the Treaty of Bakan was what ultimately pushed forward this movement. Around 1900, a group of people named The Yìhétuán (義和團) was established. They branded themselves as a martial arts cult and claimed that by repeating their mantras, followers would be "Impenetrable by blades"and "Unharmed by Cannons". This group of people were backed by the Empress Dowager Cixi at the time. Not only because this faux-populist movement can make the regime appear less like an accountable for any retaliations since it was "self-organized", but the club also changed their motto from "反清復明" (Abolish Qing Restore Ming) to "扶清滅洋" (Help Qing Defeat the West). This mantra helped perpetrate a reduction in friction between the ruling Manchurians and the ruled Han-Chinese, thereby strengthening Cixi's grasp on the country from Han Nationalists. After the repeated murders of foreign missionaries and Chinese Christians, the group ended up expanding their movement into Zhili (Modern day Hebei) and killed a German and a Japanese Embassy Staff Member. Cixi declared war against all these nations on June 15th 1900, which ultimately led to the Eight Nation Alliance between England, France, Germany, Russia, Japan, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and America. The battalion attacked China for its deeds and took over Beijing on August 15th. By October 26th, Cixi surrendered on behalf of China after escaping to Xi'an. The surrender led to the signing of the Boxer Protocol (辛丑條約) (1901), which led to war reparations and a Chinese exclusion zone withinin Beijing for security reasons: only Westerners can live within this zone in order to prevent another massacre. This ended up being one of the most disgraceful events under the Qing Dynasty. It caused much distrust towards the Manchurian Regime amongst the Chinese populace and an increased support in Sun Yat-sen's revolution. Academy of Chinese Studies. (一)列強不斷侵華與教案頻生: 中國文化研究院 - 燦爛的中國文明. chiculture.org.hk/tc/photo-story/1729. Romanization of Treaty names are taken from Wikipedia. |

Oscar Wong | ||

| 28 Mar 1898 |

Birthright CitizenshipWong Kim Ark was a person born in the United States and has lived in the United States for most of his life, however, he was denied of reentering into the United States after a visit to China in the year 1895. Despite this was not the first time he visited China, since he had one prior visit when his parents decided to go back to China, he was not allowed to re-enter into the United States because of the election of Democrat a President Grover Cleveland and the passing of the Geary Act earlier that year, which both resulted in stricter regulations of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Wong Kim Ark's parents had left the United States because of stress from law and increasing racial hatred toward Chinese. Both of which were making the business of their store harder to sustain. After going back to China, the outlook for Wong Kim Ark's career was not good. Thus, he returned to the United States in search of a job that will support him. One reason the "UNITED STATES v. WONG KIM ARK" court case was conflictual was that Wong Kim Ark's parents at the time of Wong Kim Ark's birth achieved permanent residence and supporting business in the United States. Since they "are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China", it means that they were under the "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" (UNITED STATES v. WONG KIM ARK, 1898). When writing the Fourteenth Amendment, the reason for writing and including the words "subject to the jurisdiction thereof" was to exclude ambassadors, foreign soldiers, and Native Americans at the time who did not have to pay tax from becoming citizens of the United States(Thomas, 2010). What's more, the case of Wong Kim Ark also brings into the question of is citizenship a result of "jus soli (by soil) or jus sanguinis (by blood)", which is quite problematic for Americans at that time (Thomas, 2010). If there was admittance to jus soli, then there will be admittance to thousands of black people and denial to many children born outside of the United States. If there was admittance to jus sanguini, there will still be a great number of citizens of different races within a generation (Thomas, 2010). Work Cited Citizenship [Video file]. Retrieved October 4, 2020, from Kanopy. https://purdue.kanopy.com/playlist/378649 Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service. San Francisco District Office. "An 1894 notarized statement by witnesses attesting to the identity of Wong Kim Ark. A photograph of Wong is affixed to the statement." Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. United States v. Wong Kim Ark. Web. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_v._Wong_Kim_Ark#/media/File:... Thomas, Brook. "China Men, United States v. Wong Kim Ark, and the Question of Citizenship." American Quarterly 50.4 (1998): 689-717. Web. https://purdue-primo-prod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1c3q7im/T... Thomas, Brook. "The Legal and Literary Complexities of U.S. Citizenship Around 1900." Law & Literature 22.2 (2010): 307-24. Web. https://purdue-primo-prod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1c3q7im/T... UNITED STATES v. WONG KIM ARK. Supreme Court of United States. 169 U.S. 649 (1898). https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=3381955771263111765&hl=zh-C... |

Zhiheng Jiang | ||

| 11 Dec 1897 |

Aborigines Act 1897 of Western Australia

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 20 May 1895 |

The last trial of Oscar WildeOscar Wilde was subjected to a total of three trials from March till May of 1895. The first trial saw Wilde taking the Marquess of Queensberry. The second was twenty-five counts of gross indecencies and conspiracy to commit gross indecencies. The final trial was for gross indecency, and Wilde was arrested. The third trial was the nail in the coffin. Starting on May 20th, 1895, Wilde was formally charged with seven counts of gross indecency (alos referred to as sodomy). In an effort to get a conviction, the prosecution presented only the strongest witnesses, and the trial was described as ‘gruesome’ and ‘horrifying’. Wilde was declared guilty on six counts, with the exception being Edward Shelley. He was sentenced to two years of hard labor (the maximum sentence) and served his time at Reading goal. The last two trials took place at the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, also known as Old Bailey. Wilde’s trial and the aftermath form an interesting commentary on gender, class and sex. Some of the notable follow-ups are that Lord Douglas was never formally prosecuted and was protect by his father’s status, while Wilde was thrown to the dogs. Another was the speculation that the Liberal government was especially harsh on Wilde because the then Prime Minister Archibald Primrose, Earl of Rosebery was suspected of having an affair with yet another of Queensberry’s sons. It is also interesting to note that prior to these trials, the attitude towards homosexuals was almost pitiful, but after the trial they were viewed as predatory and dangerous. And finally, it is worth noting that despite all of this, lesbianism was not criminalized, and sexual acts between women were for all intents and purposes legal. It was formally added as a part of the Criminal Law Amendment Act in 1921, but was defeated in. the House of Lords.

|

Nidhi Shekar | ||

| 20 May 1895 |

The trial of Oscar WildeOscar Wilde was subjected to a total of three trials from March till May of 1895. The first trial saw Wilde taking the Marquess of Queensberry. The second was twenty-five counts of gross indecencies and conspiracy to commit gross indecencies. The final trial was for gross indecency, and Wilde was arrested. The third trial was the nail in the coffin. Starting on May 20th, 1895, Wilde was formally charged with seven counts of gross indecency (alos referred to as sodomy). In an effort to get a conviction, the prosecution presented only the strongest witnesses, and the trial was described as ‘gruesome’ and ‘horrifying’. Wilde was declared guilty on six counts, with the exception being Edward Shelley. He was sentenced to two years of hard labor (the maximum sentence) and served his time at Reading goal. The last two trials took place at the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, also known as Old Bailey. Wilde’s trial and the aftermath form an interesting commentary on gender, class and sex. Some of the notable follow-ups are that Lord Douglas was never formally prosecuted and was protect by his father’s status, while Wilde was thrown to the dogs. Another was the speculation that the Liberal government was especially harsh on Wilde because the then Prime Minister Archibald Primrose, Earl of Rosebery was suspected of having an affair with yet another of Queensberry’s sons. It is also interesting to note that prior to these trials, the attitude towards homosexuals was almost pitiful, but after the trial they were viewed as predatory and dangerous. And finally, it is worth noting that despite all of this, lesbianism was not criminalized, and sexual acts between women were for all intents and purposes legal. It was formally added as a part of the Criminal Law Amendment Act in 1921, but was defeated in. the House of Lords.

|

Nidhi Shekar | ||

| Apr 1895 to May 1895 |

Trials of Oscar Wilde

ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Nov 1890 |

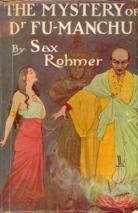

The Yellow PerilThe Yellow Peril was a term originated in Imperial Germany in the 1890s. This term was a color-metaphor referred to Western fears that Asians, particularly the Chinese, would invade their lands and disrupt Western values, such as democracy, Christianity, and technological innovation. The term of the Yellow Peril spread through Britain with the rise of Chinese populations in the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion (Nov 2, 1899 – Sep 7, 1901). The Boxer Rebellion was an uprising movement against foreigners that occurred at the end of the Qing dynasty in northern China. The Boxer did experienced suppression by allied forces in China; however, the Western anxieties continually increased, which turned into the fears of the “Yellow Peril”. The most recognizable character of “Yellow Peril” was Dr. Fu Manchu, a villain from the series of novels written by a British author Sax Rohmer. Image: A 1913 cover of Sax Rohmer’s The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Macnhu Articles: |

Shiqi Deng | ||

| 25 Jul 1890 |

Western Australian Constitution Act

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 14 Aug 1885 |

Criminal Law Amendment Act

Related ArticlesMary Jean Corbett, “On Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke, 1886″ Andrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 1873 |

Dissolution of the Samurai ClassIn the years leading up to and following 1873, the government of Japan worked to gradually dissolve the Samurai class. The government at this point in Japan’s history was working to unite the upper and lower classes and create a system where all were equal, sentiments displayed in the Meiji Restoration’s Charter Oath, a sort of founding document for the new government. So, the government began to merge ex-Samurai into the rest of society. They did so at times with incentives, such as providing lots of opportunities for ex-Samurai to find employment in government projects like land reclamation and the railway industry. They also did so at times with mandates, such as abolishing their pension system, preventing them from carrying swords, discontinuing old styles of Samurai garb, and making rulings to end their once-held legal privileges. While many were able to adjust to their new way of life, many found their new lives a poor trade for what they once had. But hey, what could a group of highly trained, proud men who were suddenly stripped of their entire identity possibly do in retribution? Oh, wait . . . Sources:

|

Reign Browning | ||

| Jun 1870 |

Civil suit against Edward John Eyre nullified

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 26 Jul 1869 |

Poor Rate Assessment and Collection Act

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Jun 1868 |

Edward John Eyre acquitted

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 15 Aug 1867 |

Second Reform Act

ArticlesJanice Carlisle, "On the Second Reform Act, 1867" Related ArticlesCarolyn Vellenga Berman, “On the Reform Act of 1832″ Elaine Hadley, “On Opinion Politics and the Ballot Act of 1872″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Apr 1867 |

Nelson and Brand charges dismissedA Middlesex grand jury at London’s Old Bailey criminal court dismissed charges brought by the Jamaica Committee against Colonel Abercrombie Nelson and Lieutenant Herbert Brand for the murder (via illegal court martial) of George William Gordon at Morant Bay, Jamaica in October 1865. The trial was a result of the Morant Bay Rebellion of 11 October 1865. Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 27 Mar 1867 |

Edward John Eyre indictment hearing

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Feb 1867 |

Trafalgar Square demonstrationMajor Reform League march and demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London on 11 February 1867. Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 2 Jul 1866 |

Hyde Park demonstrationHyde Park Demonstration of the Major Reform League on 23 July 1866. After the British government banned a meeting organized to press for voting rights, 200,000 people entered the Park and clashed with police and soldiers. Related ArticlesPeter Melville Logan, “On Culture: Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy, 1869″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Dec 1865 |

“Jamaica Committee”

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 11 Oct 1865 |

Morant Bay Rebellion

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 2 Oct 1865 |

George William Gordon executedGordon, a Jamaican former slave and elected member of the Jamaica House of Assembly, is executed by hanging after a court martial condemns him to death for his alleged role in encouraging the Morant Bay rebellion. Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Jan 1863 to Dec 1863 |

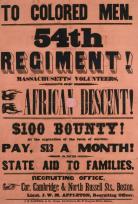

Recruitment of Colored Troops in the American Civil WarAt the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, black men were not recruited for the Union army. But two years later, the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln allowed recruitment of African Americans to fight for the Union. As an abolitionist, Massachusetts’ governor, John A. Andrew, pushed for funding and black men to join the war effort. Andrew had wanted a black regiment to fight for Massachusetts since the beginning of the war, but it wasn’t until the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation that he was able to begin recruitment for all-black regiments in Massachusetts. Andrew worked with abolitionists, both black and white, to encourage formation of an all-black regiment. Most black men were hesitant to join the United States Colored Troops (USCT), as word had gotten around that treatment of any black soldiers captured by the Confederates would be worse than treatment of a white Union prisoner. White Union officers who commanded these black soldiers would be executed if captured as well. Despite this, recruitment for a 54th and 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, all-black regiments, began just a month after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. Governor Andrew was able to enlist 1,000 men and raise money for the regiment he hoped would stand as an example for future colored regiments. Because of the worries of black men joining the Union to fight, recruitment had to be done outside of Massachusetts as well. But by May, the 54th infantry was full. The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, led by Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, is best known for the Assault on Fort Wagner. Although the 54th Massachusetts Infantry lost the battle, these soldiers showed that black men were capable of fighting for their freedom just as white men were. After their valiant efforts at the battle of Fort Wagner in July of 1863, black enlistments climbed to reach a new high. General Ulysses S. Grant wrote of the black soldiers in a letter to President Lincoln that arming Negroes was a big blow to the Confederates, saying that “these Negroes were the Union’s strong ally”. Works Consulted: Brown, Katie O’Halloran. “Letters of Black Soldiers from Ohio Who Served in the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantries during the Civil War”. Ohio Valley History, vol. 16, no. 3, 2016, p. 72-79. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/article/631460. Robbins, Peggy. “The 54th Massachusetts’ War within a War”. Military History, 2003, p. 62-70. ProQuest, https://search.proquest.com/docview/212668658?accountid=13360. |

Megan Dettmer | ||

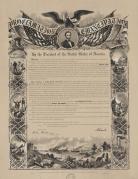

| circa. The end of the month Autumn 1862 to circa. The start of the month Spring 1863 |

Emancipation Proclamation (1862-1863)In September of 1862 Preisdent Abraham Lincoln gave the Executive Order that of January 1, 1863 that all slaves being captive in the United States is a practice of rebellion and therefore shall be forever free. Although this did not change the status of most of the 3.5 million slaves in the south, it did change the presecpective of the war. This Proclamation did not apply to the border states that were still loyal to the union, but shifted the concept of the war from preserving the orginal values of the Union to abolition agaist slavery and the future of a new America. Lincoln persoally hated slavery and felt it was a moral issue, and was already working towards gradual emancipation in those border states that were left out of the proclamation. This Emancipation had a lot of symbolic effect behind it such as countries like France and England denounced the Confederacy for supporting slavery. As the Union army started to take back control of the south these slaves were slowly freed and emancipated. This also allowed congress to push for the Militia Act which allowed men of color to serve in the military; which ended up adding a total of 200,000 soldiers by the time the war ended. The Confiscation Act was also adopted which allowed slaves siezed by the Union army to be given their freedom and declared forever free. This time line was key for the Union to gain momentum in the war and lead the country to the 13th Amendment. History.com Editors. “Emancipation Proclamation.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 29 Oct. 2009, www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/emancipation-proclamation. “Emancipation Proclamation.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 28 Sept. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emancipation_Proclamation. “Emancipation Proclamation Text.” HistoryNet, www.historynet.com/emancipation-proclamation-text. |

Edward Mooradian | ||

| Jun 1858 |

Sale of the final piece of Chartist propertyJune 1858 saw the sale of the final piece of Chartist property, definitively bringing to an end the efforts of the Chartist Cooperative Land Company. The Chartist Land Company was a large-scale, explicitly political version of freehold societies. Conceived by the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor in 1842, the Company, like freehold societies, purchased large tracts of land through subscriptions and then sold smaller parcels to subscribers. It attempted to re-create village life by building cottages, hospitals, and schools, and setting aside one hundred acres for common use. Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 10 May 1857 to 20 Jun 1858 |

Indian Uprising

ArticlesPriti Joshi, “1857; or, Can the Indian ‘Mutiny’ Be Fixed?” Related ArticlesJulie Codell, “On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 14 Mar 1856 |

Petition for Reform of Married Women’s Property LawOn 14 March 1856, presentation of the Petition for Reform of the Married Women’s Property Law, 1856. The petition began the joint effort by lawmakers and public women to grant married women control of their own wealth. ArticlesJill Rappoport, “Wives and Sons: Coverture, Primogeniture, and Married Women’s Property” Related ArticlesRachel Ablow, “‘One Flesh,’ One Person, and the 1870 Married Women’s Property Act” Anne D. Wallace, “On the Deceased Wife’s Sister Controversy, 1835-1907″ |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Aug 1851 |

Chancery Court orders closing of O’Connorville

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 29 May 1851 |

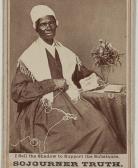

Sojourner Truth Addresses the Women’s Rights Convention of 1851 at Akron, OhioThe Women’s Rights Convention of 1851 at Akron, Ohio was one of the numerous events throughout 19thcentury United States for the extended rights of women. Numerous advocates delivered speeches at this Convention however it is best known as the venue for a former slave Sojourner Truth’s address, later popularized as “Ain’t I a Woman.” Born in 1757 as Isabella Baumfree as a slave in the Dutch-speaking Ulster County, New York, she was bought and sold into slavery four times and forced to marry a slave with whom she had five children. She was emancipated in 1827 and renamed herself Sojourner Truth in 1843 post which she became an itinerant speaker. She met abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglas who encouraged her to give speeches about the evils of slavery. She also joined forces with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthonyfor Women’s Suffrage Movement in the United States. Although she never learnt to read or write, she was a woman of uncommon courage. In her extemporaneous speech, she took a stance for the suffrage rights of women. She not only questioned the white man’s privilege and argued for women’s suffrage rights but also shed light on the additional challenges facing Black community especially Black women. Even though the Ohio Constitution of 1851 ultimately denied women the right to vote, several versions of Truth’s address which begin with the audience dissing her and concluded with a standing ovation from the same audience, definitely popularized as one of the greatest orators in the 19th century for the rights of women. Works Cited: "A Nation Being Redefined, 1975-2000 / Equal Rights Amendment / Women's Rights Convention of 1851." American History. ABC-CLIO, 2013. Web. 29 May 2013. “Sojourner Truth.” Sojourner Truth - Ohio History Central, ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Sojourner_Truth. “Sojourner Truth.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/sojourner-truth.htm.

|

Pulkit Manchanda | ||

| Dec 1849 |

Carlyle's "Negro Question"

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 19 Jul 1848 to 20 Jul 1848 |

Seneca Falls ConventionOn July 19 and 20 of 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Mary M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt came together to organize the Seneca Falls convention. This was the first woman's rights convention in the United States and launched the women’s suffrage movement. The convention was held in Seneca Falls New York at the Wesleyan Chapel. The idea for the convention was the result of Stanton and Mott meeting at an anti-slavery convention in London in 1840 where they were required to sit in a sectioned off area because they were women. Eight years later, the two of them reunited and, along with Wright, M’Clintock, and Hunt, organized and publicized the convention in just five days. Despite the short notice and the lack of solid publicity, over 300 people attended the convention. The first day of the convention was open only to women, but men joined in on the second day. Over these two days, the attendees discussed and ratified the Declaration of Sentiments, an assertion of women’s rights in the United States, and it was signed by around 100 of the attendees. This convention began the women's suffrage movement in the United States and many of the organizers dedicated their lives to gaining women the right to vote. 72 years later when women were finally granted the right to vote, only one woman who had signed the Declaration of Sentiments was alive. Works Cited History.com Editors. “Seneca Falls Convention.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 10 Nov. 2017, www.history.com/topics/womens-rights/seneca-falls-convention. Rynder, Constance B. “Seneca Falls Convention.” HistoryNet, 1999, www.historynet.com/seneca-falls-convention. |

Maggie Piercy | ||

| 19 Jul 1848 to 20 Jul 1848 |

Seneca Falls ConventionOne of the first Women's Rights Convention was the Seneca Falls Convention. It was held on July 19 and 20, 1848. It took place in Seneca Falls, New York. This meeting launched the women's suffrage movement. It would also several decades later ensure women the right to vote. The Seneca Falls Convention was held in the Wesleyan Chapel. The first day was only just for women and then the second day it was open to men. Despite the scarce publicity, 300 people attended. It was mostly just area residents that showed up. This convention will forever be an important part in history, it was one of the first times that women came together and fought for their own rights. The women came up with 11 resolutions on women’s rights, which included social, civil, and religious rights for women, All of them were accepted except the ninth one, which was the right to vote. Even though it wasn’t accepted, the fact that it was even spoken about made a big impact. The ninth resolution was eventually passed after Elizabeth Stanton and Frederick Douglass gave their passionate speeches in its defense. The five woman organizers of the convention were also apart of the abolitionist movement, which fought for the end of slavery, and racial discrimination. The five organizers were Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, Mary M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt. The Seneca Falls Convention brought national attention to the issue of women's rights. Newspapers across the U.S. covered the convention, both in support and against it. Elizabeth Stanton called the women's movement the “greatest rebellion the world has ever seen”. After everything went public, Elizabeth didn’t care about the criticism because she looked at it as it will start to get more women thinking, men too. Just to get men and women to start thinking about the issues and start raising more questions, the first step of the progress is taken. On August 2, 1848, two weeks later, the convention met up again to reaffirm the movement's goals at the First Unitarian Church in Rochester, New York. Because of the Seneca Falls Convention, over the following years the campaign continued for women's rights at nationwide and state events. History.com Editors. “Seneca Falls Convention.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 10 Nov. 2017, www.history.com/topics/womens-rights/seneca-falls-convention. “Seneca Falls Convention.” HistoryNet, www.historynet.com/seneca-falls-convention. |

Makayla Bach | ||

| 19 Summer 1848 to 21 Summer 1848 |

The First Women's ConventionThe first spark of the continuing movement of women's rights began early Wednesday morning on July 19th, 1848. In a small Methodist church located in Seneca Falls New York, the first ever women's convention was held. The convention was organized by a group of women known for their actions in political reform. The primary women included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and Susan B. Anthony. The first meeting of these women was held in one of their homes, where they discussed the utmost importance of a women's rights reform. They decided that a women's convention should be held in order to educate and spread the word of equal rights for both men and women. Cady Stanton and the other women then drafted what they titled: “The Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions”. This document was constructed by paraphrasing parts of the Original Declaration of Independence. The Document began by declaring that “all men and women are created equal”. It then proceeds into a list of subcategories staging different political injustices. Some of the Injustices included women being denied access to voting, access to higher education, and access to certain professions. Other injustices discussed women not receiving equal pay for equal work done by their male counterparts as well as women's lack of property rights without marriage. Overall the declaration consisted of over a thousand words and it concluded with the demand of these injustices being reformed. The convention lasted a total of two days and overall there were about 300 people in attendance. The first day of the convention was meant primarily for women attendance, but around 40 men showed up at Wesleyan Methodist Church. The organizers decided to let the men stay regardless of the fact that the convention was initially held specifically for women. From Wednesday morning till late Thursday evening, the group of people discussed the Declaration of Sentiments and as well as its' resolutions. They made changes to the document in areas they saw fit and then concluded the convention with a signing of the document. One hundred people signed the document and of those one hundred people 68 were women and 32 were men. The New York media coverage of the event was less than supportive. Many were upset at the suffrage idea and were less than afraid to speak their minds. Many major papers mocked the event and stated that the declaration and its ideas were downright amusing. The only paper that took the convention seriously and respected the reforms wanting to be made was the liberal New York Tribune. The New York Tribune may not have agreed with all of the events demands due to the idea that equal political rights were deemed improper. But they did bring light to the event in a manner that showed respect for the assertion of natural rights. But as word of the convention traveled locally it began to make its way beyond the state lines of New York. Soon the convention spread rather rapidly throughout the entire nation and quickly became known as the first spark of women's rights in the United States. Source: Rynder, Constance. "'All men and women are created equal.' (1848 Women's Rights Convention)." American History, vol. 33, no. 3, Aug. 1998, p. 22+. Gale Academic OneFile, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A20927186/AONE?u=purdue_main&sid=AONE&xid.... Accessed 10 Oct. 2020. |

Allie Foster | ||

| 1 Jul 1848 |

Trial of Chartist leaders

The summer of 1848 witnesses violence as Chartist leaders are arrested and secret plots against the government are infiltrated. By the end of August, after the arrest of several hundred Chartists and Irish Confederates, the movement for violent uprising in England is broken. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 10 Apr 1848 |

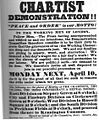

Chartist Rally, Kennington

Led by Feargus O’Connor, an estimated 25,000 Chartists meet on Kennington Common planning to march to Westminster to deliver a monster petition in favor of the six points of the People’s Charter. Police block bridges over the Thames containing the marchers south of the river, and the demonstration is broken up with some arrests and violence. However, the large scale revolt widely predicted and feared fails to materialize. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 21 Feb 1848 |

Publication of The Communist ManifestoThe first edition of "The Communist Manifesto" was anonymously published in London on 1848 February 21. Despite it was the cooperate work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the "The Communist Manifesto" was mostly written by Karl Marx "in the two months of December 1847 and January 1848." (Neil, 1998). Work Cited Findlay, Len M. "Manifest Der Kommunistischen Partei/The Communist Manifesto (review)." Victorian Review 35.1 (2009): 23-27. Web. https://purdue-primo-prod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1c3q7im/T... Harding, Neil. "Marx, Engels and the Manifesto: Working Class, Party, and Proletariat." Journal of Political Ideologies 3.1 (1998): 13-44. Web. https://purdue-primo-prod.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/f/1c3q7im/T... History.com Editors. Karl Marx Publishes The Communist Manifesto. 9 Feb. 2010, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/marx-publishes-manifesto. Stamp of the Soviet Union, 100th anniversary of "The Communist Manifesto" by Marx and Engels, CPA #1246. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Stamp_... |

Zhiheng Jiang | ||

| 17 Aug 1846 |

Opening festival for O’Connorville

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Apr 1846 |

Formation of the Chartist Land Company

Articles |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 8 Aug 1842 |

Manchester strike

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| 2 May 1842 |

Second Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier | ||

| Spring 1841 |

Trial of Madame RestellMadame Restell, or Ann Lohman, was arrested, tried, and convicted of performing an illegal abortion in the spring of 1841. The late Maria Purdy, who died of tuberculosis, made a death bed confession about the abortion operation she'd had at Madame Restell's. She blamed the complications from the abortion as the reason she developed tuberculosis and subsequently died. She had taken some of Madame Restell's "pills" but stopped because she was wary of the ingredients, and then asked her to perform an abortion. Madame Restell would be the female physician performing the operation, and it would be her last. She spent some time in prison, and would continue to run her business upon her release, but she would only sell pills and would never again perform a surgical abortion. References: Abbott, Karen. “Madame Restell: The Abortionist of Fifth Avenue.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 27 Nov. 2012, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/madame-restell-the-abortionist-of-fifth-a.... Horwitz, Rainey. “The Embryo Project Encyclopedia.” Trial of Madame Restell (Ann Lohman) for Abortion (1841) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, 10 Oct. 2017, embryo.asu.edu/pages/trial-madame-restell-ann-lohman-abortion-1841. |

Brooke Peterson |