This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research some aspect of the nineteenth century that teaches us something about race, class, or gender and sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class or gender/sex in the 19th century to our collective resources in COVE. Provide sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural detail that you are presenting. Try to interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

This timeline is part of ENGL 202's build assignment. Research some aspect of the nineteenth century that teaches us something about race, class, or gender and sexuality and then contribute what you have learned to our shared class resource. As the assignment states, "Add one timeline element, one map element and one gallery image about race, class or gender/sex in the 19th century to our collective resources in COVE. Provide sufficient detail to explain the historical or cultural detail that you are presenting. Try to interlink the three objects." A few timeline elements have already been added (borrowing from BRANCH).

Timeline

Table of Events

| Date | Event | Created by |

|---|---|---|

| 9 Apr 1787 | First settlers depart for Sierra Leone

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jan 1789 | Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 14 Jul 1789 to 14 Jul 1789 | Storming of the BastilleThe Storming of the Bastille, dated July 14th, 1789, created a disturbance in class shift in French society. The hierarchy on the upper half was the clergy, and then the nobility in that order; the third estate consisted of peasants and workers, whom of which built up 80% of the population. Despite making up such a large portion of the population, they were still below under the poverty line and treated as lesser humans. The significance behind the Bastille is it was not just a normal prison; it was used as a monarch-operated prison as the king could imprison anyone he felt was a danger to his rule. The main intention of the protestors was to overwhelm the guards and gain control of the weapons beings stored within. The actual storming happened within a single day, as it started with negotiations between the Third Estate and the guards of the Bastille, but quickly turned violent as peasants stormed the prison. Although this one event did not single-handedly bring down the class structure implemented into France’s society, it was quite possibly the largest event in the broader category of the Revolution of 1789. However, what the Storming of the Bastille did contribute to was the lynching of two big figures under the monarchy, Joseph Foullon De Doue (the head of finances) and Louis Bénigne François Bertier de Sauvigny (an attendant). It also inspired the population around France to create municipalities for civic government. Works Cited: Dowson, Thomas. Finding Remains of the Bastille in Paris Today. 14 July 2019, archaeology-travel.com/travel-reports/where-is-the-bastille-today/. History.com Editors. “Bastille Day.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 21 June 2017, www.history.com/topics/france/bastille-day. “Storming of the Bastille in the French Revolution.” History Crunch - History Articles, Summaries, Biographies, Resources and More, www.historycrunch.com/storming-of-the-bastille.html. “Storming of the Bastille.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 7 Oct. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storming_of_the_Bastille. |

Nate Hood |

| 1 Jan 1792 | Vindication of the Rights of Woman

ArticlesAnne K. Mellor, "On the Publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 22 Jun 1802 | Criminal Jurisdiction Act passed

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Mar 1814 to Jun 1827 | New Harmony, IndianaOriginally founded by the Harmonie society under the leadership of German Immigrant George Rapp, New Harmony, Indiana was formed due to the increasing populations and costs of land in Harmony, Pennsylvania, that threatened their desire for solitude. A religious society with aspects of German culture, New Harmony found great success along the Wabash river. In stark contrast to the society following it, it was extremely well planned, self-sufficient with it's own factories and workers. They thrived until 1824, when George Rapp received a prophecy about the second coming of Christ, forcing him to move back to Pennsylvania. When he put the town up for sale, it was bought by Robert Owen, a wealthy industrialist and socialist who hoped to eliminate the growing class divide of the industrial revolution. He sought to bring together scholars and academics from all over the US, but let anyone join the society. Because of this, there was a large shortage of skilled craftsmen, and poor management and planning. In 1826, in an effort to unite this society, they wrote a new constitution, which was based on equal rights and duties, which would also hopefully bring more management to the society and train the children to become skilled craftsmen. But this was not enough to unite the people, as Robert Owen himself was a flawed leader. For one he had an open distaste for organized religion, which split much of the community. His ideals drove away farmers, upset anarchists, and divided the common people. And finally, he struggled to receive the same amount of donations that he had in Europe. Due to this disorganisation and lack of unity, New Harmony, Indiana broke apart into smaller, separate communities in 1827, and then eventually entirely dissolved in 1829. Works Cited (Timeline)

“New Harmony, Indiana.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 10 Aug. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Harmony,_Indiana.

Owen, William. Diary of William Owen fromto April 20, 1825. ed by Hiatt, Joel W Indianapolis, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1906. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/10014024/>. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “New Harmony.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 22 July 2011, www.britannica.com/place/New-Harmony. Wilson, William Edward. The Angel and the Serpent: the Story of New Harmony. Indiana University Press, 1992. |

Steven Kelly |

| 15 Feb 1819 | Sandy Brow FightOn 15 February 1819, William Fitton presided at a public meeting at Sandy Brow in Stockport (the so-called “Sandy Brow Fight”), number present not known, where a scuffle involving stones and brickbats occurred over an attempt by the military to seize the Cap of Liberty; the Riot Act was read three times. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 28 Jun 1819 | Stockport meetingOn 28 June 1819, at the great Stockport meeting, the largest of its kind besides Peterloo, upwards of 20,000 assembled to hear Sir Charles Wolseley speak on Parliamentary reform. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 12 Jul 1819 | Britain approves settlement scheme to South AfricaOn 12 July 1819, the British government approved £50,000 for a settlement scheme to South Africa's eastern Cape. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 16 Aug 1819 | Peterloo massacre

Related ArticlesJames Chandler, “On Peterloo, 16 August 1819″ Sean Grass, “On the Death of the Duke of Wellington, 14 September 1852″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| 30 Dec 1819 | Gag Acts

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1824 | Prostitution as a Working Class OccupationIn Victorian England, most women were supposed to be the breadwinners of their families. The Town Police Clauses Act of 1847 made prostitution illegal in public places. To make a living, they were expected to sell their bodies in the streets. The streets were often crowded with people. Children had lived on the streets. However, not all prostitutes were poor. There were three classes of prostitutes. The upper-class prostitutes were for the rich. In contrast, the lower-class prostitutes were only for the poor. The middle-class prostitutes were able to serve the rich and the poor. Prostitutes were even educated. Mostly the upper-class prostitutes. The lower-class prostitutes didn't know how to read or write. In the earlier 1800s, there weren't many occupations available for women in England. Factory work and street vendors were hazardous work. Women who were smart and had job skills didn't make enough money to provide for their families. The only job that woman could make a lot of money from is prostitution. Prostitution was the fourth-largest female occupation in the world. It was legal in England, but it was only illegal for prostitutes to gather groups in England's streets. Prostitutes also couldn't be drunk in public. If a woman was drunk in public, she could face up to a year in prison. Reformatories were also a place women had to go to when breaking the law. Reformatories were far worst than prison. It was rehab for prostitutes. Sources Aiken, Dianne. "Victorian Prostitution." British Literature Wiki. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Feb 2012 https://sites.udel.edu/britlitwiki/victorian-prostitution/ Joyce, Fraser. "Prostitution and the Nineteenth Century: In Search of the 'Great Social Evil' https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/reinvention/archive/volume1issue1/joyce |

Faith Harris |

| 28 May 1830 | Indian Removal ActIn the spring of 1830, United States President Andrew Jackson signed into order the Indian Removal Act. This act forced Native American tribes out of the land they were already living in because that land was considered to be a part of the American state. Jackson wanted this new "American" land to be settled and tamed by those who were considered American citizens (primarily white men). In signing this act, Jackson promised the Native Americans that they could live in the mostly unsettled lands west of the Mississippi, however, he made it clear that they were not welcome to stay within American borders. As an incentive, Jackson promised the native tribes that if they left their homelands willingly, the government would help them move to their new homes and give them material goods to make their lives easier. He also promised them that they would be under the protection of the United States government forever. Because of these promises, a handful of tribes left willingly. Most tribes did not immediately follow Jackson's instruction, however, as they had signed treaties with the United States government before, and it never ended well for the tribes. This caused many tribes to be removed with force. As a direct result of this act, the "Trail of Tears" occurred, where many native people lost their lives journeying from their homelands to the untamed west. Drexler, Ken. “Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History” Library of Congress, 22 Jan. 2019, guides.loc.gov/indian-removal-act#:~:text=The%20Indian%20Removal%20Act%20was,many%20resisted%20the%20relocation%20policy. Accessed 6 Oct. 2020. |

Samantha Shriver |

| Aug 1830 to Dec 1830 | Swing Riots

Related ArticlesCarolyn Lesjak, "1750 to the Present: Acts of Enclosure and Their Afterlife" (forthcoming) |

David Rettenmaier |

| 30 Oct 1831 | Riots at BristolOn 30 October 30 1831, a crowd of 10,000 took possession of Queen Square in Bristol, as rioting in nine cities and towns marked the failure of the second version of the First Reform Bill in the House of Lords. Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jun 1832 | Reform Act

ArticlesCarolyn Vellenga Berman, “On the Reform Act of 1832″ Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 29 Aug 1833 | Slavery Abolition Act

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1 Aug 1838 | Molesworth ReportOn August 1838, the Molesworth Report was published, beginning the Dissolution of Convict Transportation to Australia. The report successfully built upon the rhetoric of the abolition movement by drawing connections between convicts and slaves, becoming one of the major deciding factors in eventually putting an end to the entire system of transportation. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

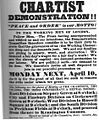

| 14 Jun 1839 | First Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 28 Aug 1839 to 30 Aug 1839 | The Eglinton TournamentDefined by Oxford Dictionary as “the inferred responsibility of privileged people to act with generosity and nobility toward those less privileged.” Naturally, many of us would immediately think of class, and how it was the “responsibility” of the nobles to “act with generosity and nobility” towards the lower classes. But it also happens to apply to the inferred responsibility that men have to women, adults towards children, and, of course, anyone “inferior.” The idea of noblesse oblige was based on the idea of “medieval chivalry,” which had become an increasingly popular image triggered when Kenelm Digby published The Broad Stone of Honour in 1822 (Dryden 17-8). This idea became almost perfectly exemplified in Earl Archibald William Montgomerie of Eglinton’s intention when hosting the Eglinton tournament in 1839, in an attempt to revive medieval chivalry to a more common way of life. More specifically stated, Montgomerie’s intention was desired to be a demonstration of romanticism, which was an age that preferred a more medieval approach than a classical one. This meant returning certain ideas such as that of the chivalry of a gentleman, which embodied “bravery, loyalty, courtesy, modesty, purity and honour and endowed with a sense of noblesse oblige towards women, children and social inferiors (in Mangan and Walvin 113)” (Dryden 18). And while many called it an “absolute fiasco,” it was also one that “emanated from the minds...uncomfortable with industrial, urban England” (Dryden 18 ; Tyrell 2010). Whether it was an event that was from the minds of those who were uncomfortable with urbanization or not, it was clear that the deficiencies of the event did nothing to discourage the idea that chivalry applied to men of all classes, much less to discourage noblesse oblige. One of the other characteristics of a chivalrous gentleman was that he was polite and deferential to women of every class, which bridges yet another divide between classes, especially when taking into consideration that Queen Victoria of England was the embodiment of a woman worthy of a knight’s devotion. Given, she was the queen and it was part of her job to embody a woman worthy of a knight’s devotion, it became even more clear that women of every class should follow her example. The only drawback of being chivalrous is that it only applies to and for those who are devout Christians. Anyone else would either be too barbaric or otherwise unworthy of receiving any form of noblesse oblige.

Works Cited Dryden, L. Joseph Conrad and the Imperial Romance. London-United Kingdom, United Kingdom, Palgrave Macmillan, 1999. Tyrrell, Alex. “A Card King? The Earl of Eglinton and the Viceroyalty of Ireland.” The Historian, vol. 72, no. 4, 2010, pp. 866–887. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24454753. Accessed 7 Oct. 2020. |

Shikha Pandey |

| Nov 1839 | Newport Uprising

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 2 May 1842 | Second Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 8 Aug 1842 | Manchester strike

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 22 Oct 1844 | The Great DisappointmentReverend William Miller (1782-1849) was comparable to other baptist preachers of the time during the Second Great Awakening. However, during the 1830s he partnered with Joshua V. Himes another well known and respected baptist minister. The two gained traction with the media and public as they began outwardly expressing thier views on the second comming of Christ. While the interpretation of christian scripture at the time was that Christ would come again to save beleivers, and condemn everyone else to eternal damnation, the time of this event was not clearified through scripture. This is why it was so polarizing for Miller and Himes to propose that they knew what day it would be, as well as being in thier near future. Ultimately looking back it is clear that these predictions were wrong, but Miller was wrong multiple times. The following he had created initially predected that the end would come on March 21, 1843. However Miller never confirmed this date, allowing himself to be more genrous by saying that it would be that year. However, this date and year would come and pass with no sign of an apocolypse. Miller would even predict some more dates before his final prediction of October 22, 1844. As the day came and went it became known as the, "Great Dissapointment". Even into his death Miller insisted that the endof the world they knew was close. Sources: “The Millerites and Early Adventists, 1840-1870.” ProQuest, about.proquest.com/products-services/film/the-millerites-and-early-adventists-1840-18701.html. Norwood, K. “Vermont Digital Newspaper Project (VTDNP).” Vermont Digital Newspaper Project VTDNP, Flickr, 21 Mar. 2015, library.uvm.edu/vtnp/?p=2765. |

Caleb Holzhausen |

| Apr 1846 | Formation of the Chartist Land Company

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 17 Aug 1846 | Opening festival for O’Connorville

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 10 Apr 1848 | Chartist Rally, Kennington

Led by Feargus O’Connor, an estimated 25,000 Chartists meet on Kennington Common planning to march to Westminster to deliver a monster petition in favor of the six points of the People’s Charter. Police block bridges over the Thames containing the marchers south of the river, and the demonstration is broken up with some arrests and violence. However, the large scale revolt widely predicted and feared fails to materialize. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1 Jul 1848 | Trial of Chartist leaders

The summer of 1848 witnesses violence as Chartist leaders are arrested and secret plots against the government are infiltrated. By the end of August, after the arrest of several hundred Chartists and Irish Confederates, the movement for violent uprising in England is broken. ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

David Rettenmaier |

| Autumn 1849 to 1863 | Harriet Tubman Introduced to Underground RailroadThe general of the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman, was first introduced to the secrecy of this organization in 1849. Through her journey of rescuing and transporting slaves, her ability to master the art of escaping led her to save over seventy fugitives without losing a single member. She began this act by first saving herself, then returning to bring freedom upon her family. In total, she made 13 trips from the south to many northern states, as well as, Canda. These trips journeyed on foot would take around five days and three weeks to complete. Not only was she a master of escape, but she also understood the beauty of a helping hand. This was witnessed through her providing assistance to many soldiers: nursing, cooking, and laundering. Her personality was not one of fear and retreat. For example, she led an attack on her enemies of the south commonly known as the Combahee River Raid. To further help fugitives, she guided around 700 of them on the battlefield. In her later life, she showed a passion for women's suffrage by vocally representing her views and opinions. In 1908 the opening of the Harriet Tubman Home for Aged and Infirm Negroes, her reputation was further boosted. Works Cited: Conrad, Earl. “I Bring You General Tubman.” The Black Scholar, vol. 1, no. 3-4, 1970, pp. 2–7., doi:10.1080/00064246.1970.11430666. “Harriet Tubman.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Oct. 2020, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harriet_Tubman. Lasch-Quinn, Elisabeth. “Harriet Tubman: An American Idol.” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 43, 2004, pp. 124–129. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4133571. Accessed 12 Oct. 2020. |

McKensy Hoskins |

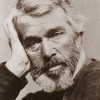

| Dec 1849 | Carlyle's "Negro Question"

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 23 Oct 1850 to 24 Oct 1850 | First National Women's Rights ConventionIn 1850, the first National Women's Rights Convention was held in Worcester Massachusetts and Paulina Wright Davis was the primary organizer for the movement. This historic convention oversaw the discussion on women's rights with "representatives from nine states" attending this convention to see to the 'question of Women's Rights, Duties and Relations', (Quarles). The convention lasted two days, running from October 23-24. Women and men from different backgrounds came together from all different places, including the Midwest and the Northeast to call on giving women equal rights as men, such as, the right to vote as well as to own their own property. Word was even spread to Britain where a woman by the name of Harriet Taylor heard about it and wrote about all that had happened within the convention over the course of the two days. This convention came two years after the Seneca Falls Convention in New York where the discussion on women's rights was first brought up and launched the beginnings of the talk for equal rights amongst women and men. It was organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton who would end up continuing to be a part of the women's suffrage movement during the First National Women's Rights Convention. It ended up having a profound impact on emphasizing the issues women are facing and putting priority on giving women equal rights. The Declaration of Sentiments was a document signed by many that was outlined similar to the Declaration of Independence. The Seneca Falls convention altogether paved the way for future conventions, such as the National Women's Rights Convention in Worcester. The National Women's Rights Convention meeting began with Davis giving a profound address on the objective of the conventions and amount of injustice there is in the world while speaking on the fact that inequality is a problem in the United States and women should be seen and heard. She demanded and listed the necessary steps that should be taken for women's equal rights, such as with the foucs on education and allowing women to be educated as well as go to univerisites. Many other advocates came in support of this issue and calling to action the need for equaility; these people include, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriot Hunt, as well as others. Abby H. Price made an address on human rights and how men and women were created equally. She wanted to focus on equal opportunity in being employed as well as the workplace, political rights for women and men, women should have independence apart from men. Women should not be treated lower than men, they should be respected and act as their own person rather than viewed as property by men. This was a convention that would continue the fight for equal rights for women and would give people the chance to address this issue more promiently. Quarles, Benjamin. “Frederick Douglass and Women's Rights.” Jstor, The University of Chicago Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2714400?origin=crossref&seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents. |

Mackenzie Shaffer |

| Aug 1851 | Chancery Court orders closing of O’Connorville

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 10 May 1857 to 20 Jun 1858 | Indian Uprising

ArticlesPriti Joshi, “1857; or, Can the Indian ‘Mutiny’ Be Fixed?” Related ArticlesJulie Codell, “On the Delhi Coronation Durbars, 1877, 1903, 1911″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1858 | English Woman’s Journal first published

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jun 1858 | Sale of the final piece of Chartist propertyJune 1858 saw the sale of the final piece of Chartist property, definitively bringing to an end the efforts of the Chartist Cooperative Land Company. The Chartist Land Company was a large-scale, explicitly political version of freehold societies. Conceived by the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor in 1842, the Company, like freehold societies, purchased large tracts of land through subscriptions and then sold smaller parcels to subscribers. It attempted to re-create village life by building cottages, hospitals, and schools, and setting aside one hundred acres for common use. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 2 Oct 1865 | George William Gordon executedGordon, a Jamaican former slave and elected member of the Jamaica House of Assembly, is executed by hanging after a court martial condemns him to death for his alleged role in encouraging the Morant Bay rebellion. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 11 Oct 1865 | Morant Bay Rebellion

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Dec 1865 | “Jamaica Committee”

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 2 Jul 1866 | Hyde Park demonstrationHyde Park Demonstration of the Major Reform League on 23 July 1866. After the British government banned a meeting organized to press for voting rights, 200,000 people entered the Park and clashed with police and soldiers. Related ArticlesPeter Melville Logan, “On Culture: Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy, 1869″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| 11 Feb 1867 | Trafalgar Square demonstrationMajor Reform League march and demonstration in Trafalgar Square, London on 11 February 1867. Related Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 27 Mar 1867 | Edward John Eyre indictment hearing

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 11 Apr 1867 | Nelson and Brand charges dismissedA Middlesex grand jury at London’s Old Bailey criminal court dismissed charges brought by the Jamaica Committee against Colonel Abercrombie Nelson and Lieutenant Herbert Brand for the murder (via illegal court martial) of George William Gordon at Morant Bay, Jamaica in October 1865. The trial was a result of the Morant Bay Rebellion of 11 October 1865. Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 15 Aug 1867 | Second Reform Act

ArticlesJanice Carlisle, "On the Second Reform Act, 1867" Related ArticlesCarolyn Vellenga Berman, “On the Reform Act of 1832″ Elaine Hadley, “On Opinion Politics and the Ballot Act of 1872″ |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jun 1868 | Edward John Eyre acquitted

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| circa. The middle of the month Sep 1868 to circa. The end of the month Aug 1904 | Lydia Thompson's contribution to 19th Century Burlesque Theater in AmericaBurlesque Theater was first introduced in America in the 1840s and quickly gained popularity for its sexually suggestive performances, witty dialogue, and revealing costumes. Burlesque performances originated in London but gained attention in America due to its resemblance to minstrel shows. When Burlesque shows were first established in America, they primarily centered around humorous sketches but later shifted to more elements of strip tease in the early 20th century. Although the shows themselves were not primarily risqué, audiences flocked to theaters in order to observe women portraying their sexuality on stage. To this day, scholars continue to study the impact that these performances had not only on the historical elements of stage performance, but on women’s sexuality as it pertains to the arts. To further understand Burlesque theater, Robert G. Allen, author of Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture states the following: “Without question, however, burlesque’s principal legacy as a cultural form was its establishment of patterns of gender representation that forever changed the role of the woman on the American stage and later influenced her role on the screen. The very sight of a female body not covered by the accepted costume of bourgeois respectability forcefully if playfully called attention to the entire question of the “place” of women in American society.” - Robert G. Allen, Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (Univ. of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1991), pp. 258-259. An important historical figure in the Burlesque movement was Lydia Thompson (1838-1908). Lydia, otherwise known as the “queen of Burlesque” was the first woman to wear tights on stage in 19th Century England. Thompson, along with her Burlesque troupe “The British Blondes,” made history in autumn of 1868 when they introduced Victorian Burlesque to New York Theatres. Their first production, “Ixion, or, The Man at the Wheel” shocked audiences in America because the women wore revealing tights and were seen depicting male roles. Additionally, the women wrote and produced this production with no assistance from a male counterpart. This event was pivotal in American theater because it was the first instance that a Victorian Burlesque troupe had attempted to independently perform a theatrical production depicting males. The production was immensely popular and attracted the attention of both men and women across America. In fact, Thompson and her troupe made over $370,000 in their first season in America. Thompson’s female driven Burlesque shows in the late 1860’s sparked much debate. Most audience members applauded the women for fighting against the standards set for women during these times. In both England and America, women were pressured to dress modestly and primarily wear only long dresses that wouldn’t draw attention to their figures. These women were going against these societal standards and pushing for a society that allowed women to openly express their sexuality without fear of repercussion. However, the women did face backlash for their actions. While most audiences enjoyed the stance against societal pressure on women, the press thought otherwise. Comments in newspaper publications deemed Thompson as a prostitute and claimed that her blonde hair was a wig. Some reporters went so far as to call the women immoral. Wilbur Storey, owner of The Chicago Times, had a significant amount of negative feedback for the women and labeled the women as “low and degrading.” In response, Thompson and her troupe went to Storey’s home and beat him with a horsewhip. The women were charged with assault, however the incident made audiences fall even more in love with the women and their performances. Shows were selling out even quicker and the women were benefiting from the increase in sales. In later years when questioned about the Storey incident, Thompson responded, “The persistent and personally vindictive assault in the Times upon my reputation left me only one mode of redress...They were women whom he attacked. It was by women he was castigated… We did what the law would not do for us.” Although Burlesque theater still has several negative connotations to its name in present day America, Thompson and her troupe made strides in both theatrical productions and the feminist movement. Their passion to stand up for their sex left audiences with a deeper understanding of the societal pressure that women were facing during this time. (The dates referenced in this entry include the start of Thompson’s troupe to Thompson's final performances) Works Cited: Allen, R. (n.d.). Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (Cultural Studies of the United States). Greer, K., Kane, L., Leonard-Rose, M., Morrison, M., Staveski, C., Sigrid Freeburg, R., Bench, H. (2015, October 21). Spectacles of Agency and Desire: The British Blondes and The Media. Retrieved from https://scalar.usc.edu/works/spectacles-of-agency-and-desire/the-british-blondes-and-the-media.8 Accessed 6 October 2020. Shields, D. (n.d.). Lydia Thompson. Retrieved from https://broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/lydia-thompson. Accessed 6 October 2020. |

Sarah Litteral |

| 26 Jul 1869 | Poor Rate Assessment and Collection Act

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jun 1870 | Civil suit against Edward John Eyre nullified

Articles |

David Rettenmaier |

| 9 Jun 1870 | The Death of Charles DickensCharles Dickens was a prolific author in the Victorian era, and his death in 1870 marked a turning point in the literature of the time. The endings of these novels while Dickens was alive tended to be happy, rewarding the characters for their good Victorian values. After his death, the endings became grimmer and more realistic. Throughout the period, though, there was a focus on the characters' struggles throughout their lives, often with a stance on a social issue of the day. Dickens often chose to write about the lower classes and the hardships they faced, demonstrated in one of his best-known books, A Christmas Carol, by the characters of the Cratchit family. |

Kate Fuesz |

| 18 Mar 1871 to 28 May 1871 | The Paris CommuneThe Paris Commune was a 71 day socialist uprising in the heart of Paris, France. The preceeding half century up to this point, the Parisians became more and more discontent with the way the French government operated. Despite their attempts to shift the discourse to the left by overthrowing the Orleanist monarchy and replacing it with the second French Republic, Napoleon III seized power and announced the creation of the second French Empire. Parisians grew in anger and a revolutionary fire began to burn in their hearts. They all agreed that the monarchy must go, but many had shifted all the way into anarchist and/or Marxist extremism. So when the Franco-Prussian War erupted, they had no support from the Monarch to protect them. Paris was essentially left defenceless. The wealthy all fled the city before Prussian siege began. Many Parisians began to starve. Paris was left destitute after the war and daily protests plagued the city for weeks. Being abandoned by its governing body meant that Paris was directly controlled by the main French Government. So the Parisians, desiring more local governance, appointed their own city council. The Paris Commune was born. While they never directly declared independence from France, the laws that the Paris City Council passed were in direct opposition to the president of France, Adolphe Thier’s strict economic regulations. Additionally, many of the laws that the Paris Council passed were reflective of Leftist ideology, and for this reason it is memorialized in history as one of the first attempts at a socialist society. Among their legislation were the following: The separation of church and state, the abolishment of death penalty, and ending conscription. There was also several large women’s movement that emerged place during this time, and much of the commune had a foundation in a struggle against capitalism and the patriarchy. Though, much of the struggle would never be fully realized due to the short time the Commune lasted. Nathalie Lemel created the Women’s Union for the Defence of Paris and Care of the Wounded. Elisabeth Dmitrieff created The Union des Femmes which brought women more control over their own labor and demanded equality of wages for women. However, despite all these large steps, the Commune never nationalised anything. In fact, one of the biggest Leftist criticisms of the Commune is that the Parisians worked together with the bank of France located in Paris, rather than raid and steal all the gold. Eventually, Thier amassed an army that could take back Paris and over the course of The Bloody Week. Works Cited: Hoffenberg, Peter H. “1871-1874: The South Kensington International Exhibitions.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. 9 Oct 2020 Eichner, Carolyn Jeanne. Surmounting the Barricades Women in the Paris Commune. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2004. Web. 8 Oct 2020 Merriman, John M. Massacre : The Life and Death of the Paris Commune. 2014. Web. 8 Oct 2020 |

Andrew Kotecki |

| 14 Aug 1885 | Criminal Law Amendment Act

Related ArticlesMary Jean Corbett, “On Crawford v. Crawford and Dilke, 1886″ Andrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier |

| circa. Autumn 1887 | "Ten Days in a Mad-House" ReleasedNellie Bly, an American journalist, releases her book, Ten Days in a Mad-House. The book reflects Bly’s ten day experience going undercover into a female only insane asylum. The asylum was located on Blackwell Island, which was filled only by the asylum, a poorhouse, a smallpox hospital and a prison. She describes the asylum as so horrid that it made her “look insane.” The asylum was freezing cold with poor food and consisted of several women who had no reason to be there. Some were immigrants and were mistakenly committed to the asylum because they couldn’t understand English, and some were just poor and believed they were going to the poorhouse on the island. Not long after her book was published and received overwhelming support, the asylum was given $1 million more dollars to improve the conditions. Bly broke barriers as being one of the first successful female journalists and earning a reputation as a “stunt girl.” Bly was under an immense amount of pressure, as neither her nor her editor believed she’d be able to convince experts that she was insane and needed to be admitted into an asylum. To make her act believable, she explains that she looked in the mirror and tried to reflect all qualities she has seen in “crazy people.” Her alias was a Cuban immigrant who suffered from amnesia. She would stay in boarding houses and refuse to sleep or eat and would wander around and yell out random phrases. Eventually, one of the assistant matrons called the police and she was then admitted into Blackwell Asylum. While in the asylum, Bly explains that she acted somewhat calm and the doctors and officers would say there was no hope for her to recover because she was “positively demented.” She writes that these doctors did not really know for sure if these people belonged in an asylum. In the asylum, Bly met many different people who she didn’t feel belonged in the asylum. One was a German woman who spoke very little English and could not put together a case that the court would understand to prove she was not crazy. This woman was sent away for life “without even being told in her language why and wherefore.” There were over 1600 women in the asylum, with poor conditions throughout. These conditions made the women sick and would often make them seem crazier than they really were. They were treated inhumane, and when Bly was able to be released from the asylum, she published this book and gained the attention of people in high power. They were able to expand the budget of the asylum which improved the conditions tremendously. Bly’s written experience was a major step in reforming asylums and stopping the racism and sexism that were the cause of thousands of people’s admittance.

Source: Bly, Nellie. Ten Days in a Mad-House. 2017. Associated Articles: Blackwell's Island (Roosevelt Island), New York City (U.S. National Park Service). www.nps.gov/places/blackwell-s-island-new-york-city.htm. |

Kelly Matsuoka |

| 28 Jul 1893 to 19 Sep 1893 | New Zealand: The First Country to Grant National Voting Rights to WomenOn July 28th, 1893 a suffrage petition signed by 'Mary J. Carpenter and 25,519 Others' was submitted to the New Zealand Parliament. Less than two months later on September 19th, 1893, Lord Glasgow, governer of New Zealand during the time period, signed a new Electoral Act into law. With the signing of this act, New Zealand was the first self-governing country in the world that enacted women's right to vote in elections. This was a huge step in the world wide women suffrage movement, although most other democracies, such as Britain and the United States, did not give women the right to vote until after World War 1. The passing of the Electoral Act was made possible by the years of effort from suffrage campaigners in the country that were led by Kate Sheppard who also founded the Women's Christian Temperance Union two years before becoming the leader of the suffrage movement in New Zealand. A series of massive petitions written with the act of calling Parliament to grant women's right to vote took three years to compile together before they were able to submit the entirety of the New Zealand Women Suffrage Petition that had 25,520 signatures in total on it. The peitition stetches more than 270 meters long and is on display at the National Library of New Zealand in Wellington. After New Zealand granted women the right to vote, the British Colony of South Australia was the next to follow, granting full suffrage in 1894. The start of the 20th Century saw the effect of these great advances in the suffrage movement spread to many other countries around the world and sparked the passing of many laws in support of women's suffrage. Works Cited: “Kate Sheppard.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 2 Apr. 2014, www.biography.com/activist/kate-sheppard. “Suffrage Petition, 1893.” New Zealand Government, 13 Mar. 2018, nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/womens-suffrage/petition. “Women and the Vote.” New Zealand Government, 20 Dec. 2018, nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/womens-suffrage. Women's Suffrage Movement - Facts and Information on Women's Rights. www.historynet.com/womens-suffrage-movement. |

Vanessa Heltzel |

| Apr 1895 to May 1895 | Trials of Oscar Wilde

ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 3 Apr 1895 to 25 May 1895 | The Trials of Oscar WildeOscar Wilde, born on October 16, 1854, was widely known across London as one of the most popular poets and playwrites, but later became more known for his trials and later criminal conviction for "gross indecency" under the 1895 Criminal Law Amendment Act, which made it a crime to commit any acts of "gross indecency," or in other words, incriminate anyone who performs sexual activity with another individual of the same sex. Wilde was put on trial because of Lord Alfred Douglas' father, John Sholto Douglas, who was concerned about the relationship Wilde had built with his son. The trials of Oscar Wilde caused homosexuals to become more of a threat to the public eye, and people were much less tolerant of them. Same sex couples who were looked over before the trials became suspect after, and people in same sex friendships became anxious of giving the public reason to believe they were in a sexual relationship. Art also began to be associated with homo eroticism, and feminine characteristics in a man immediately offered the idea of homosexuality. Works cited: Linder, Douglas O. The Trials of Oscar Wilde: An Account. http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/wilde/wildeaccount.html |

Grace Kuhlman |

| 11 Oct 1899 to 31 May 1902 | Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 17 May 1900 | Siege of Mafeking lifted

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 30 Nov 1900 | Death of Wilde

ArticlesEllen Crowell, “Oscar Wilde’s Tomb: Silence and the Aesthetics of Queer Memorial” Related ArticlesAndrew Elfenbein, “On the Trials of Oscar Wilde: Myths and Realities” |

David Rettenmaier |

| Jun 1901 | Hobhouse report on Second Boer War

ArticlesJo Briggs, “The Second Boer War, 1899-1902: Anti-Imperialism and European Visual Culture” |

David Rettenmaier |

| 1909 | Clemence and Laurence Housman found the Suffrage AtelierFollowing the formation of the Artists' Suffrage League, founded by renowned stained glass artist, Mary Lowndes, in 1907, which produced illustrated banners, postcards, and pamphlets used to promote the campaign for women's enfranchisement in Britain and North America, Clemence and Laurence Housman established their own Suffrage Atelier in 1909. Its practices took place at artists' homes, before the Housman siblings offered the site of their small home, Pembroke Cottage in Kensington, as its headquarters. Though the location of its headquarters would change three more times within its five operational years, the collective vision of the Atelier remained the same: it was to act as an arts and crafts society which worked towards the enfranchisement of women, with an additional effort to encourage artists to forward the women's movement by means of pictorial publications. (VADS, "The Women's Library: Suffrage Banners") In contrast with its predecessor, the Artists' Suffrage League, the Housmans' Suffrage Atelier encouraged non-professional visual artists and enthusiasts to submit their work to the cause in addition to professional artists, and also offered a small percentage of the sold works' profits as compensation. The Atelier also contrasted with its associates, the Women's Freedom League (1907-61) and the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) (1903-17), stylistically, by means of the colours its members chose to use in the creation of its feminist propaganda. While the other organizations used white, green, and purple, which are commonly known as the defining colours of the suffrage movement, the Atelier used a broader range of hues, as depicted in one of its banners (at left), wherein blue, black, and gold are used. Clemence led the team, and also lent her talents as an embroiderer, illustrator, and wood engraver to the Atelier, often spending entire days sitting on a floor cushion, doing her needlework or engraving in order to benefit the cause. Laurence designed a number of the Atelier's banners. As Clemence Housman was a respected member of the WSPU, much of the Atelier's work could be found for purchase within its store chains and also within the pages of its national newspaper. The Atelier held printmaking workshops and competitions in addition to the numerous exhibitions, political rallies and processions its members would regularly attend and circulate their artwork at, while also allowing for new and meaningful relationships to be forged between women as they worked collaboratively to aid a feminist cause which married the artistic with the political. The feminist nature of the workshop's artistic operations also subverted the common belief that embroidery and needlework reinforced women's domestic place within the home. The Suffrage Atelier ran from 1909-14. (Morton, "Changing Spaces: Art, Politics, and Identity in the Home Studios of the Suffrage Atelier") |

Alex Heath |

| circa. 1940 to circa. 1973 | Homosexual Aversion TherapyHomosexual aversion therapy notaby began in the early 1940s. Homosexuality, bisexuality, and transsexuality were viewed as sexual deviances caused by psychological maladaption. Queer patients were often taken to mental asylums involuntarily by family to be "cured", and aversion therapy was one of the many methods scientists attempted to do this. It was believed that conditioning patients to associate the sex they found attractive with unpleasant stimulus would cause them to lose their attraction and turn heterosexual. Doctors would take patients to viewing rooms and project images of people each patient would be attracted to. If they showed any signs of attraction or interest in the picture, the doctors would administer the unpleasant stimulus. The most notable of these stimuli was electroshock waves. Injecting drugs into the patient to cause nausea and vomiting was also common. Eventually, patients would associate these images with the shocks or drugs, and would be averse to looking at the screen. Continued exposure showed that, after time, this dislike would also be applied to real time, and patients would get upset looking at any member of their once-preferred sex. The cruelty of aversion therapy and other conversion methods eventually became a talking point in the psychological field. Human rights activits began to work for protections of queer people and make involuntary conversion illegal. As the century progressed, aversion therapy waned in popularity. In 1973, the American Psychiatric Associaton removed homosexuality from its list of diagnosable mental disorders. Treatment for the "condition" was no longer sanctioned. While this did not end the practice of aversion therapy, it did limit it, and the controversy around the practice made it extremely unpopular as more time passed. Today, queer aversion therapy is illegal in many states or countries. It is still used in some states, and has been expanded to try and deter sexual offenders like pedophiles. Sources: Blakemore, Erin. "Gay Conversion Therapy's Disturbing 19th Century Origins." History.com, 2019, www.history.com/news/gay-conversion-therapy-origins-19th-century. Accessed 7 October 2020. Chenier, Elise. “Aversion Therapy.” GLBTQ Archive, 2015, www.glbtqarchive.com/ssh/aversion_therapy_S.pdf. Accessed 7 October 2020. Editors of Encylopedia Britannica. Aversion Therapy. 23 Nov. 2018, www.britannica.com/science/aversion-therapy. Accessed 9 October 2020. |

Allison Hicks |