First settlers depart for Sierra Leone

9 Apr 1787

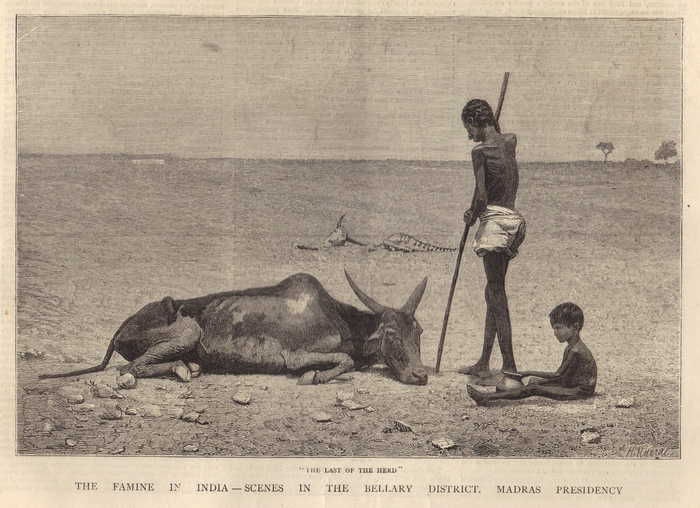

On 9 April 1787, 451 people set sail to establish a “Province of Freedom” in Africa, later to become Sierra Leone. Image: An illustration of liberated slaves arriving in Sierra Leone, from the 1835 book, A System of School Geography Chiefly Derived from Malte-Brun, by Samuel Griswold Goodrich. This image is in the public domain in the United States as its copyright has expired.

On 9 April 1787, 451 people set sail to establish a “Province of Freedom” in Africa, later to become Sierra Leone. Image: An illustration of liberated slaves arriving in Sierra Leone, from the 1835 book, A System of School Geography Chiefly Derived from Malte-Brun, by Samuel Griswold Goodrich. This image is in the public domain in the United States as its copyright has expired.

Articles

Isaac Land, “On the Foundings of Sierra Leone, 1787-1808″

Associated Places

Vasto, ItalySierra Leone