British Literature since 1660s: Liberty and Subjection

Created by Ruixue Zhang on Sat, 12/10/2022 - 15:33

Part of Group:

This timeline roughly lays out major events after the Restoration until the 1960s. There are some events that are not shown here so we will discover and discuss them together along with the major works we read in class.

Timeline

Chronological table

| Date | Event | Created by | Associated Places | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1660 |

Charles II Restored to the English ThroneThe return of Charles Stuart (son of the beheaded King Charles I) marks the beginning of the Restoration age. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1662 |

Act of UniformityThe Act requires all clergy to obey the Church of England. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1662 to 1664 |

Great Plague of LondonGreat Plague of London ravaged London from 1664 to 1666. City records indicate that some 68,596 people died during the epidemic, though the actual number of deaths is suspected to have exceeded 100,000 out of a total population estimated at 460,000. The outbreak was caused by Yersinia pestis, the bacterium associated with other plague outbreaks before and since the Great Plague of London. The Great Plague was not an isolated event—40,000 Londoners had died of the plague in 1625—but it was the last and worst of the epidemics. It began in London’s suburb of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, and the greatest devastation remained in the city’s outskirts, at Stepney, Shoreditch, Clerkenwell, Cripplegate, and Westminster, quarters where the poor were densely crowded. An outbreak was suspected in the winter of 1664, but it did not spread intensely until the spring of 1665. King Charles II and his court fled from London in the early summer and did not return until the following February; Parliament kept a short session at Oxford. In December 1665 the mortality rate fell suddenly and continued down through the winter and into early 1666, with relatively few deaths recorded that year. From London the disease spread widely over the country, but from 1667 on there was no epidemic of plague in any part of England, though sporadic cases appeared in bills of mortality up to 1679. The disappearance of plague from London has been attributed to the Great Fire of London in September 1666, but it also subsided in other cities without such cause. The decline has also been ascribed to quarantine, but effective quarantine was actually not established until 1720. Scholars generally agree that the cessation of plague in England was spontaneous. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1673 |

The Test ActThe Test act required all holders of civil and military offices to take the sacrament in an Anglican church and to deny belief in transsubstantiation. Protestant Dissenters and Roman Catholics were larged excluded from public life. Samuel Butler's Hudibras (1663) illustrates the religious exclusion and zealot. (Norton Anthology of English Literature: The Restoration and the Eighteenth Century pp 4) |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1681 |

Charles II dissolved ParliamentCharles II dissolved the Parliament after conflicts in religious and political issues, especially after the House of Commons tried to force him to exclude his Catholic brother, James from succession to the throne. This crisis also led to the division of the country between two new political parties: the Tories, who supported the king, and the Whigs, who opposed the king. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1685 |

James II took the throneJames II, Charles II's brother, a Catholic, took the throne when Charles died. James claimed the rights to make his own laws, suspended the Test Act, and began to fill the goverment and army with Catholics. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1688 to 1689 |

The Glorious RevolutionThe Glorious Revolution happened when King James II was dethroned and his daughter Mary II and her husband William III, ascended. When King James II came into power, his overt Roman Catholicism alienated the majority of the population. The revolution was motivated both politically and religiously and was thus very complex. In the end it gave parliament more control over the monarchy which eventually led to the formation of a more political democracy. To get into more detail, King James II was Catholic and issued a Declaration of Indulgence suspending penal laws against Catholics (the laws that punish its offenders) and granted acceptance of some Protestant nonconformists. He then formally dissolved his Parliament and attempted to create a new Parliament that would support him unconditionally in his catholic ways of governing and beliefs. Feeling that Catholic dynasty was imminent, the Wigs, who were the main group that opposed catholic succession, were especially outraged.

The fear of King James succeeding in this only grew when in 1688, King James II had a son, James Francis Edward Stuart, that pushed his older Protestant daughter Mary out of the spot as his heir. It became especially worrisome to nonconformists, which were the majority of the country, when King James II announced that his new son and heir would be raised catholic.

With these new announcements and the growing terror of the public, seven of James’s peers wrote to the Dutch leader William of Orange, saying that they would pledge their allegiance to him if he agreed to invade England. William was already planning to take military action against England, so these letters only encouraged him more.

King James had prepared for military attacks though and left London in order to bring his forces to meet the invading army that were backed by William of Orange. However, several of James’s men, including his family members, deserted him, and instead sided with William’s cause.

James then attempted to flee after returning to London in fear of his safety but was captured. He again tried to leave and successfully made it to France where his Catholic cousin Louis XIV held the throne. King James died there in Exile in 1701.

It was then that the new Convention Parliament met and after significant pressure from William, agreed to a joint monarchy with William as king and James’s daughter, Mary, as Queen. The joint monarchy agreed to more restrictions from parliament, and signed what would become a Bill of Rights, as well as the right for regular Parliaments, free elections, and freedom of speech in Parliament. They also forbade the monarchy form being Catholic. Historians believe that this Bill of Rights was the first step towards a constitutional monarchy. This is the point in history that has ultimately led to Parliament’s increasing power in Britain while the monarchy’s influenced has waned. |

Blyss Bolger | ||

| 1702 |

Succession of Queen AnneAnne was born in the reign of Charles II. On Charles's instructions, Anne and her elder sister Mary were raised as Anglicans. After Mary's death in 1694, William reigned alone until his own death in 1702, when Anne succeeded him. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1707 |

Act of Union with ScotlandScotland becomes part of Great Britain |

Stacey Kikendall | ||

| 1710 |

The Statute of AnneThe Statute of Anne, also known as the Copyright Act 1710, was the first statute to provide for copyright regulated by the government and courts, rather than by private parties. It was formally put as "An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of Copies, during the Times therein mentioned." Prior to the statute's enactment in 1710, copying restrictions were authorized by the Licensing of the Press Act 1662. These restrictions were enforced by the Stationers' Company, a guild of printers given the exclusive power to print—and the responsibility to censor—literary works. The censorship administered under the Licensing Act led to public protest; as the act had to be renewed at two-year intervals, authors and others sought to prevent its reauthorisation. In 1694, Parliament refused to renew the Licensing Act, ending the Stationers' monopoly and press restrictions. The Statute of Anne prescribed a copyright term of 14 years, with a provision for renewal for a similar term, during which only the author and the printers to whom they chose to license their works could publish the author's creations. Following this, the work's copyright would expire, with the material falling into the public domain. Despite a period of instability known as the Battle of the Booksellers when the initial copyright terms under the Statute began to expire, the Statute of Anne remained in force until the Copyright Act 1842 replaced it. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1714 |

George I became the kingGeorge I (great-grandson of James I) became the king after Queen Anne's death. The Tory government was replaced by Whigs. During George's reign, the powers of the monarchy diminished and Britain began a transition to the modern system of cabinet goverment led by a prime minister. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1721 |

Robert Walpole became the Prime MinisterThe Whig representative Robert Walpole was the first prime minister of Britain, who installed dependents in government offices and controlled the House of Commons by financially rewarding its members. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1727 |

George I dies, George II becomes kingGeorge II was George I's son. |

Stacey Kikendall | ||

| 1737 |

Licensing ActThe Licensing Act is a defunct Act of Parliament. Its purpose was to control and censor what was being said about the British government through theatre. The Lord Chamberlain was the official censor and the office of Examiner of Plays was created under the Act. The Examiner assisted the Lord Chamberlain in the task of censoring all plays from 1737 to 1968. The Examiner read all plays which were to be publicly performed, produced a synopsis and recommended them for licence, consulting the Lord Chamberlain in cases of doubt. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1746 |

Jacobite Rebellion endsCharles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie)'s defeat at Culloden ends the last Jacobite rebellion |

Stacey Kikendall | ||

| 1756 to 1763 |

Seven Years' WarThe Seven Years' War was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the Carnatic Wars and the Anglo-Spanish War (1762–1763). The opposing alliances were led by Great Britain and France respectively, both seeking to establish global pre-eminence at the expense of the other. Along with Spain, France fought Britain both in Europe and overseas with land-based armies and naval forces, while Britain's ally Prussia sought territorial expansion in Europe and consolidation of its power. Long-standing colonial rivalries pitting Britain against France and Spain in North America and the West Indies were fought on a grand scale with consequential results. Prussia sought greater influence in the German states, while Austria wanted to regain Silesia, captured by Prussia in the previous war, and to contain Prussian influence. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1768 |

Captain James Cook's voyages to Australia and New ZealandJames Cook made three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and to New Zealand and Australia in particular. The first one was in 1768. He made detailed maps of Newfoundland prior to making three voyages to the Pacific, during which he achieved the first recorded European contact with the eastern coastline of Australia and the Hawaiian Islands, and the first recorded circumnavigation of New Zealand. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1775 to 1783 |

American RevolutionAmerican colonies rebel against British rule |

Stacey Kikendall | ||

| 1783 |

The Peace of ParisThe Peace of Paris of 1783 was the set of treaties that ended the American Revolutionary War. On 3 September 1783, representatives of King George III of Great Britain signed a treaty in Paris with representatives of the United States of America—commonly known as the Treaty of Paris (1783)—and two treaties at Versailles with representatives of King Louis XVI of France and King Charles III of Spain—commonly known as the Treaties of Versailles (1783). The previous day, a preliminary treaty had been signed with representatives of the States General of the Dutch Republic, but the final treaty which ended the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War was not signed until 20 May 1784. The treaty dictated that the British would lose their Thirteen Colonies and marked the end of the First British Empire. The United States gained more than it expected, thanks to the award of western territory. The other Allies had mixed to poor results. France got its revenge over Britain after its defeat in the Seven Years' War, but its material gains were minor (Tobago, Senegal and small territories in India) and its financial losses huge. It was already in financial trouble and its borrowing to pay for the war used up all its credit and created the financial disasters that marked the 1780s. Historians link those disasters to the coming of the French Revolution.[2] The Dutch did not gain anything of significant value at the end of the war. The Spanish had a mixed result; they regained Menorca and Florida, but Gibraltar remained in British hands. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 1789 |

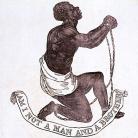

Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade Founded "Am I Not A Man And A Brother?" medallion created as part of anti-slavery campaign by Josiah Wedgwood, 1787. The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, and sometimes referred to as the Abolition Society or Anti-Slavery Society, was a British abolitionist group formed on 22 May 1787. The society was established by twelve men; including prominent campaigners Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp, who, as Anglicans, were able to be more influential in Parliament than the more numerous Quaker founding members. The society worked to educate the public about the abuses of the slave trade, and achieved abolition of the international slave trade when the British Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act 1807, at which time the society ceased its activities. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 5 May 1789 to 10 Nov 1799 |

French Revolution

On 5 May 1789, the Estates-General, representing the nobility, the clergy, and the common people, held a meeting at the request of the King to address France’s financial difficulties. At this meeting, the Third Estate (the commoners) protested the merely symbolic double representation that they had been granted by the King. This protest resulted in a fracture among the three estates and precipitated the French Revolution. On 17 June, members of the Third Estate designated themselves the National Assembly and claimed to represent the people of the nation, thus preparing the way for the foundation of the republic. Several pivotal events followed in quick succession: the storming of the Bastille (14 July), the approval of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (26 August), and the march on Versailles that led to the enforced relocation of the royal family to Paris (5-6 October). These revolutionary acts fired the imagination of many regarding the political future of France, and, indeed, all of Europe. The republican period of the revolution continued in various phases until 9-10 November 1799 when Napoleon Bonaparte supplanted the government. ArticlesDiane Piccitto, "On 1793 and the Aftermath of the French Revolution" |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 21 Jan 1793 |

Execution of King Louis XVI

1793 was a key juncture in the revolution, beginning with this execution on 21 January. The increasing violence prompted Britain to cut its ties to France, leading to declarations of war by the two countries. Violence peaked during the Reign of Terror (5 September 1793 – 27 July 1794), which resulted in the execution of the Queen (16 October) as well as of many suspects of treason and members of the Girondins, the more moderate faction that the radical Jacobins brought down on 2 June 1793 ArticlesDiane Piccitto, "On 1793 and the Aftermath of the French Revolution" |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 5 Sep 1793 to 27 Jul 1794 |

Reign of Terror

On 5 September 1793, the National Convention, France’s ruling body from 1793 to 1795, officially put into effect terror measures in order to subdue opposition to and punish insufficient support for the revolution and the new regime. From the autumn of 1793 until the summer of 1794, thousands of people across the country were imprisoned and executed (including the Queen) under the ruthless leadership of Maximilien Robespierre. The guillotine, particularly the one in Paris’s Place de la Révolution, served as the bloody emblem of the fear tactics that began to manifest themselves first in the formation of the Committee of Public Safety (6 April 1793) and subsequently in the implementation of the Law of Suspects (17 September 1793). The Terror ended on 27 July 1794 with the overthrow of Robespierre, who was guillotined the next day. ArticlesDiane Piccitto, "On 1793 and the Aftermath of the French Revolution" |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 1795 |

Gagging ActsThe Gagging Acts refer to two acts of Parliament passed in 1817 by Conservative Prime Minister Lord Liverpool. They were also known as the Grenville and Pitt Bills. The specific acts themselves were the Treason Act 1817 and the Seditious Meetings Act 1817. These acts were passed within a series of bills by the government in order to curb and suppress reformist demands by campaigners and corresponding societies, culminating in the Six Acts of 1819, after the Peterloo Massacre. |

Ruixue Zhang | ||

| 23 May 1798 to Aug 1798 |

Rebellion In IrelandA rebellion led by the Society of United Irishmen started and ended in 1798. It lasted a short 3 months and was fought by many poorly armed soldiers in a poorly organized fashion. Regardless, the death toll numbered within the tens of thousands. The main goal of this rebellion was to proclaim the country independent from Britain and create the Irish Republic. MP was published 16 years after the uprising was put down. Feelings of revolution and unrest were common feelings within the world Austen was writing in at the time. In chapter 2 of MP, Maria and Julia fault Fanny for not knowing geography, particularly relating to Ireland. They tell their mother, "Do you know, we asked her last night which way she would go to get to Ireland; and she said, she should cross to the Isle of Wight. She thinks of nothing but the Isle of Wight, and she calls it the Island, as if there were no other island in the world." Dorney, John. "The 1798 Rebellion – a brief overview." The Irish Story, 28 |

Jessie Taylor | ||

| 9 Nov 1799 to 18 Jun 1815 |

Napoleonic Wars

Historians do not agree on the exact beginning or end of the wars. November 9, 1799 is an early candidate since that is when Napoleon seized power in France. Hoping to ease the difficulty, historians date by isolated wars. They disarticulate the Napoleonic Wars in a linear series:

The successive numerical coordinates for the Coalitions offer regularity, but that regularity is undercut by the shifting make-up of that Coalition (sometimes Prussia was in, sometimes not; sometimes Russia, sometimes not) and by the discontinuity and ambiguity of the dates. Articles |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 1801 |

1801 Ireland joins Great BritainParliamentary Union of Ireland and Great Britain. Act of Union passed in 1800, took effect in 1801 |

Stacey Kikendall | ||

| 1802 |

Treaty of AmiensThis Treaty was what stopped the Neopolenic war between France and Britian. During this time France regained most of their colonies. After this treaty took place the size of the militia in Britian shrank tremendously. Change in the malitia may have cheanged hwo the women an military men interacted and may have took some of the stresses of war off of Jane and her brothers.

“French and British Armed Forces.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., https://www.britannica.com/event/Napoleonic-Wars/French-and-British-arme.... |

Jolie Falcon | ||

| 18 Jun 1815 |

Battle of Waterloo

Related ArticlesSean Grass, “On the Death of the Duke of Wellington, 14 September 1852″ Mary Favret, "The Napoleonic Wars" Frederick Burwick, “18 June 1815: The Battle of Waterloo and the Literary Response” |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 16 Aug 1819 |

Peterloo massacre

Related ArticlesJames Chandler, “On Peterloo, 16 August 1819″ Sean Grass, “On the Death of the Duke of Wellington, 14 September 1852″ |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 1 Apr 1829 |

Roman Catholic Relief Act

The Catholic Relief Act of 1829 allowed Catholics to become Members of Parliament and to hold public offices, but it also raised the property qualifications that allowed individuals in Ireland to vote. The passage of the Catholic Relief Act marked a shift in English political power from the House of Lords to the House of Commons. The Act was led by the Duke of Wellington and passed despite initially serious opposition from both the House of Lords and King George IV. ArticlesRelated ArticlesCarolyn Vellenga Berman, “On the Reform Act of 1832″ Sean Grass, “On the Death of the Duke of Wellington, 14 September 1852″ |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 15 Sep 1830 |

Opening of Liverpool & Manchester Railway

Articles

|

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 30 Oct 1831 |

Riots at BristolOn 30 October 30 1831, a crowd of 10,000 took possession of Queen Square in Bristol, as rioting in nine cities and towns marked the failure of the second version of the First Reform Bill in the House of Lords. Related Articles |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 29 Aug 1833 |

Slavery Abolition Act

Articles |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 29 Aug 1833 |

Factory Act

ArticlesRelated Articles |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 1837 to 1840 |

ChartismChartism was a British working class reform movement that emerged amid the economic depression between 1837-1838. The name comes from the People’s Charter, a bill drafted by a radical in London named Willian Lovett in 1838. The People’s Charter had six demands, universal manhood suffrage, equal electoral districts, vote by ballot, annually elected parliaments, payments of members of Parliaments, and abolition of property qualifications for membership. William Lovett was a secretary and one of the original founders of an organization called the London Working Men’s association, an organization created in 1836 that primarily appealed to skilled laborers and championed for general education. The organization also aligned itself with Owenite Socialism, a form of utopian socialism named after British social reformer Robert Owen. The core philosophy in which Owen’s essays, “ A New View of Society; or, Essays on the Principle of the Formation of the Human Character,” is based on is the belief that human character is formed by circumstances over which individuals have no control.” The Chartist movement wasn't very successful, in 1839 A Chartist convention had met in London in February to prepare a petition to present to Parliament. “Ulterior measures” were threatened should Parliament ignore the petition, but the delegates disagreed on how much militant action should be used and the convention failed. Later that year in May the movement had moved to Birmingham where riots had led to the arrest of the movement's leaders William Lovett and John Collins. In the following month the convention returned to London and presented its petition in July which Parliament had rejected. This was followed in November by an armed uprising of Chartists at Newport, which was quickly suppressed. Its principal leaders were banished to Australia, and nearly every other Chartist leader was arrested and sentenced to prison. The Chartists then started to organize under more moderate tactics. Three years later a second national petition was presented achieving more than three million signatures, but again Parliament refused to consider it. The movement began to lose momentum in the 1840s as the economy had started to return. Source: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Owen#ref5434 |

Larry Blicharz | ||

| 1839 to 1860 |

The Opium WarsOpium Wars 1-1839-1842-Britain vs China 2-1856-1860-Britain and France vs China Britain went to war with China twice in the Victorian Era. These wars are called the Opium wars because opium was at the heart of both conflicts. Beginning in the 1700s, Britain imported many Chinese products, including silk, porcelain, and tea. The problem, from the British point of view, was that the Chinese didn’t seem to want anything the British had to offer (including cotton) and demanded silver for their products. This did not make the East India Trading Company—the major player in British trade at the time—very happy. Someone, somewhere, came up with the idea to grow opium and sell it to the Chinese. “…by the 1820s, the balance of trade was reversed in Britain’s favour, and it was the Chinese who now had to pay with silver” (Hayes). The Chinese didn’t like this at all. They “…recognized that opium was becoming a serious social problem and, in the year 1800, it banned both the production and the importation of opium. In 1813, it went a step further by outlawing the smoking of opium and imposing a punishment of beating offenders 100 times.” Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough and by 1838, 40,000 opium chests were being smuggled into China each year. China had enough and stopped foreign trade. In response to the stoppage of trade and because of an attitude that “…that China was out of touch with “civilized” nations,” Britain fought back and in 1839 the first Opium War began. In the end, Britain won both wars and forced China to open their doors to trade and forced the legalization of opium use. There are two reasons I find these wars interesting. The first is that in all the books we read this semester, silk is associated with the upper-class. That means that the obsession/expectation that the landed gentry and aristocracy had in wearing these fabrics contributed to the Opium Wars. The second fascinating thing about the Opium Wars is that China ceded Hong Kong to Britain in the Treaty of Nanjing. This is the beginning of the political/social problem we see in the news today as Hong Kong reverts to China. The ramifications of these wars, that ended over 160 years ago, are continuing today. https://asiapacificcurriculum.ca/learning-module/opium-wars-china |

Dianne Freestone | ||

| 14 Jun 1839 |

First Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| Nov 1839 |

Newport Uprising

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 17 Jul 1841 |

Punch launchedOn July 17 1841, Punch, a mass-circulation periodical, was launched. Articles |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 1842 |

Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing)Under this treaty, the first of a series of so-called "unequal treaties" and the one which ended the First Opium War, Hong Kong was ceded in perpetuity to Britain. The Chinese were forced to allow Western trade, formerly restricted only to Canton (Gaunghzhou) at five "treaty ports": Canton, Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Ningpo (Ningbo), and Foochowfoo (Fuzhou). |

Ross Forman | ||

| 2 May 1842 |

Second Chartist Petition

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 14 May 1842 |

The Illustrated London News launched

Articles |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 8 Aug 1842 |

Manchester strike

ArticlesChris R. Vanden Bossche, "On Chartism" Related ArticlesJo Briggs, “1848 and 1851: A Reconsideration of the Historical Narrative” |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 1845 to 1852 |

The Great FamineThe Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger and the Potato Famine, was a disaster caused by a fungus known as potato blight. Diseased crops, plus laws put in place to allow exporting crops from Ireland, led to about 1 million deaths, primarily in the rural areas of Ireland. Because of England's inaction, the Irish would grow to resent the English and tensions between both countries would grow. During the famine, many Irish people would immigrate to America in hope of a better life. The following article provides a detailed look into the causes, experiences, and aftermath of the Great Famine. In particular this article goes into detail on the Irish who would settle in America, and the trials that faced them. |

Lydia Gottshall | ||

| circa. 1846 |

1846 Repeal of the Corn Laws

COVE Timeline Assignment: 1846 Repeal of Corn Laws The British Corn Laws, or laws that regulated imported grains and food, were influenced by both economic and political conditions in Britain. The purpose of the tariffs were to keep people from buying forgien corn products and, in turn, force people to buy domestic corn products. This was meant to stimulate Britain's economy by enforcing domestic industry practices; it was also enacted to heavily favor the rich landholders who were invested in farmland production. The Corn Laws would not allow foreign corn into Britain unless domestic corn reached a price of 80 shillings per quarter (Vamplew 3). These laws offered a “significant degree of protection to British cereal producers” (Vamplew 11) who made huge profits from grain production. Landowners, seizing the majority of monetary profit, also retained much of the political power at the time; the act of voting was reserved for those who owned land. Thus, the beneficiaries of the Corn Laws were not the common people who were forced to buy grain at an absurdly high price, but the few lucky enough reap the benefits.

While Britain's common people suffered from poverty, starvation and unsanitary living conditions, they were upset by the increasing price of grain products. Many had to quit their jobs because they were ill or they needed to take care of family members; those who did earn a wage used most of it to buy grain products to survive. The middle class was desperate for reform-- not wanting to suffer like those impacted by Irish in the Irish Potato Famine-- and wanted representation in their government. Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey, author of From the Corn Laws to Free Trade: Interests, Ideas, and Institutions in Historical Perspective, writes “In sum, repeal was an attempt to moderate the mounting pressures for parliamentary reform: by satisfying the middle class industrialist with repeal, the drive to gain control of parliamentary seats would cease, and, moreover, the working class Chartist movement (seeking more radical reform of Parliament) would lose momentum” (16). The repeal of the Corn Laws was a motion intended to “settle down” the middle class by lowering the cost of grain products and thus progressing to a free market economy.

In addition to political reform, the repeal of the Corn Laws may have been the aftermath of a growing population; Betty Kemp, author of “Reflections on the Repeal of the Corn Laws” writes, “The simplest argument for the repeal of the Corn Laws is that the rapid growth of population' in the nineteenth century, which made it necessary to import increasing quantities of wheat, also made it un- justifiable to tax those imports” (3). Thus, a booming need for more materials lead to the repeal of the Corn Laws. This repeal, led by Sir Robert Peel, was a victory for the middle class (Kemp 2) and “the final triumph of the Free Trade move- ment” (Thomas 2) which sought to lower prices on grain and provided the economy with various trade options. Supplemental Material

Works Cited Kemp, Betty. "Reflections on the Repeal of the Corn Laws." Victorian Studies 5.3 (1962): 189-204. Schonhardt-Bailey, Cheryl. From the corn laws to free trade: interests, ideas, and institutions in historical perspective. Mit Press, 2006. Thomas, J. A. "The Repeal of the Corn Laws, 1846." Economica 25 (1929): 53-60. Vamplew, Wray. "The protection of English cereal producers: the Corn Laws reassessed." The Economic History Review 33.3 (1980): 382-395. |

Rebecca Cybulski | ||

| Sep 1848 |

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood founded

Related ArticlesElizabeth Helsinger, “Lyric Poetry and the Event of Poems, 1870″ Morna O’Neill, “On Walter Crane and the Aims of Decorative Art” Linda M. Shires, "On Color Theory, 1835: George Field’s Chromatography" |

Dave Rettenmaier |

|

|

| 1 May 1851 to 15 Oct 1851 |

Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was an event in the history of: exhibitions; world’s fairs; consumerism; imperialism; architecture; collections; things; glass and material culture in general; visual culture; attention and inattention; distraction. Its ostensible purposes, as stated by the organizing commission and various promoters, most notably Prince Albert, were chiefly to celebrate the industry and ingeniousness of various world cultures, primarily the British, and to inform and educate the public about the achievement, workmanship, science and industry that produced the numerous and multifarious objects and technologies on display. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Crystal Palace (pictured above) was a structure of iron and glass conceptually derived from greenhouses and railway stations, but also resembling the shopping arcades of Paris and London. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations became a model for World’s Fairs, by which invited nations showcased the best in manufacturing, design, and art, well into the twentieth century. ArticlesAudrey Jaffe, "On the Great Exhibition" Related ArticlesAviva Briefel, "On the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition" Anne Helmreich, “On the Opening of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, 1854″ Anne Clendinning, “On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25″ Barbara Leckie, “Prince Albert’s Exhibition Model Dwellings” Carol Senf, “‘The Fiddler of the Reels’: Hardy’s Reflection on the Past” |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 2 Oct 1853 to 30 Mar 1856 |

Crimean War

ArticlesStefanie Markovits, "On the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade" |

Dave Rettenmaier | ||

| 30 Mar 1856 |

Treaty of ParisOn 30 March 1856, signing of the Treaty of Paris, ending the Crimean War. Image: Treaty of Paris, the participants (Contemporary woodcut, published in Magazin Istoric, 1856). This image is in the public domain in the United States because its copyright has expired. ArticlesStefanie Markovits, "On the Crimean War and the Charge of the Light Brigade" |

Dave Rettenmaier |