The Quomodo Organistrum Construatur is Written

circa. 1200 to circa. 1299

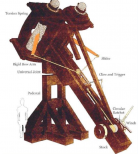

The earliest clear influence in the playing mechanism of the viola organista does not necessarily come from bowed instruments themselves. Rather, the hurdy-gurdy is a more concrete example of the method of sound generation that da Vinci was searching for. The hurdy-gurdy is an instrument similar to a violin, with a hand crank to vibrate the strings and keys to signify specific notes. While the instrument was depicted in various forms throughout the 12th century, the first manuscript detailing how to divide the tuning into a diatonic scale was released in the 13th century, titled the Quomodo Organistrum Construatur. The author of this piece is debated, as the person it is often attributed to, Odo of Cluny, died centuries before the volume was completed. Separate instruments including various combinations of wheel-cranks and keys were combined and refined in this document. These instruments were likely used for newly written polyphonic music in Catholic monasteries, including ones in Italy. One string was typically designated for drones, allowing for much easier creation of polyphonic parts, as the player did not need to actively play the string separately because of the unified hand-crank.

Severini, G. (2018, December 17). Organistrum / Symphonia keyboard in Santiago de Compostela cathedral. Retrieved from liuteriaseverini.it/index.php?…...

Hurdy-gurdy (Medieval). (n.d.). Retrieved May 14, 2019, from caslabs.case.edu/medren/mediev…

Hurdy-Gurdy [Digital image]. (2005, February 17). Retrieved from pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plik:Hur…